The Kinks’ Ray Davies on drugs, mortality, and his volatile relationship with his brother: ‘I have a dark side’

While the frontman was always the more subdued of his bandmates, especially compared to his riotous younger brother, he has his share of Swinging Sixties stories to tell. As The Kinks celebrate their 60th anniversary, Chris Harvey finds the musician, now 79, on reflective form post-tooth extraction

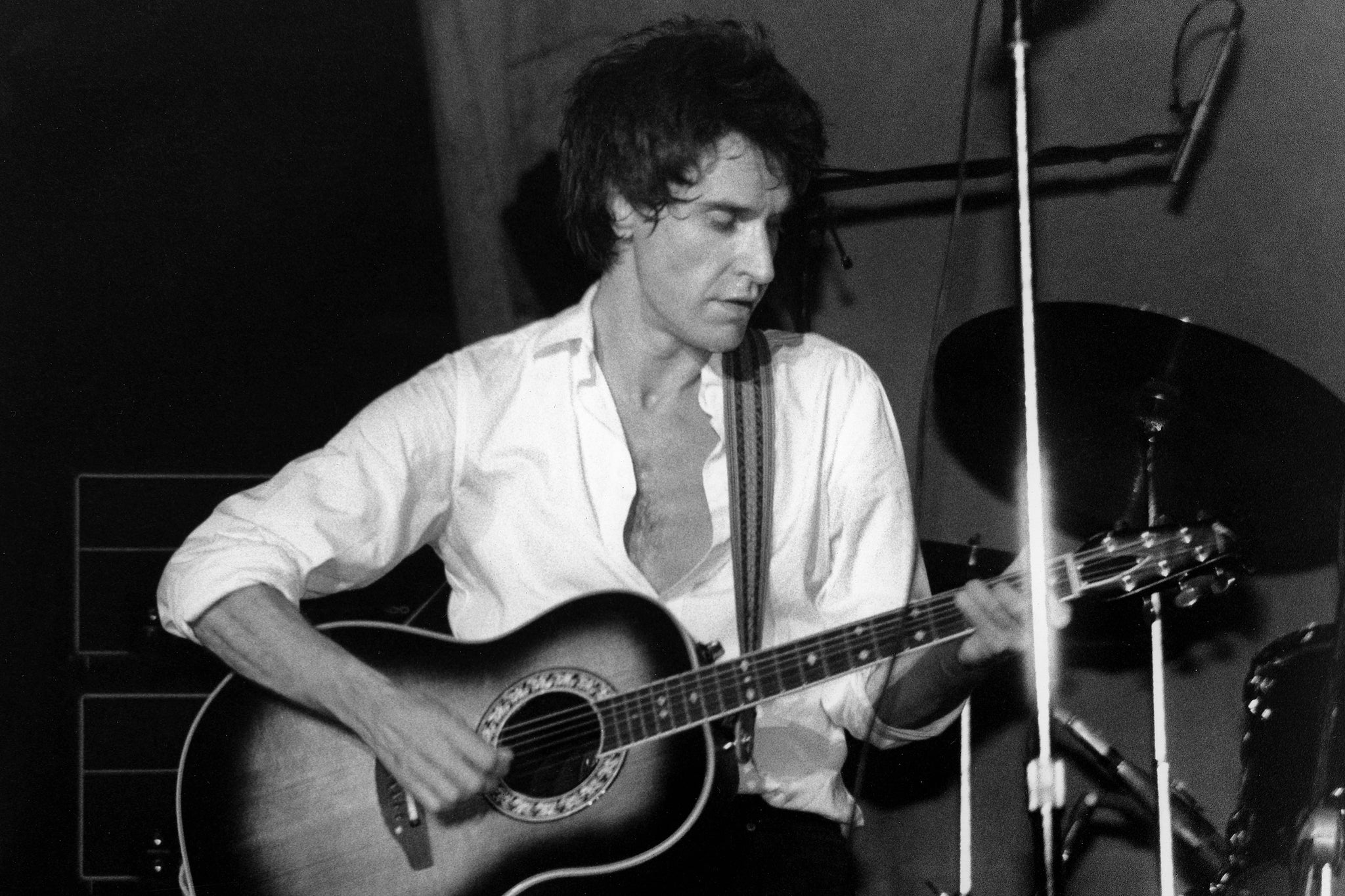

We were a working-class band with upper class aspiration,” says Ray Davies. “Born at a wonderful time in an evolving world. I hope I reflected some of that world in my songs.” The 79-year-old is chatting over Zoom about the second of the two-part collection, The Journey, released this week to mark 60 years of his band The Kinks, of which Davies remains lead singer and rhythm guitarist.

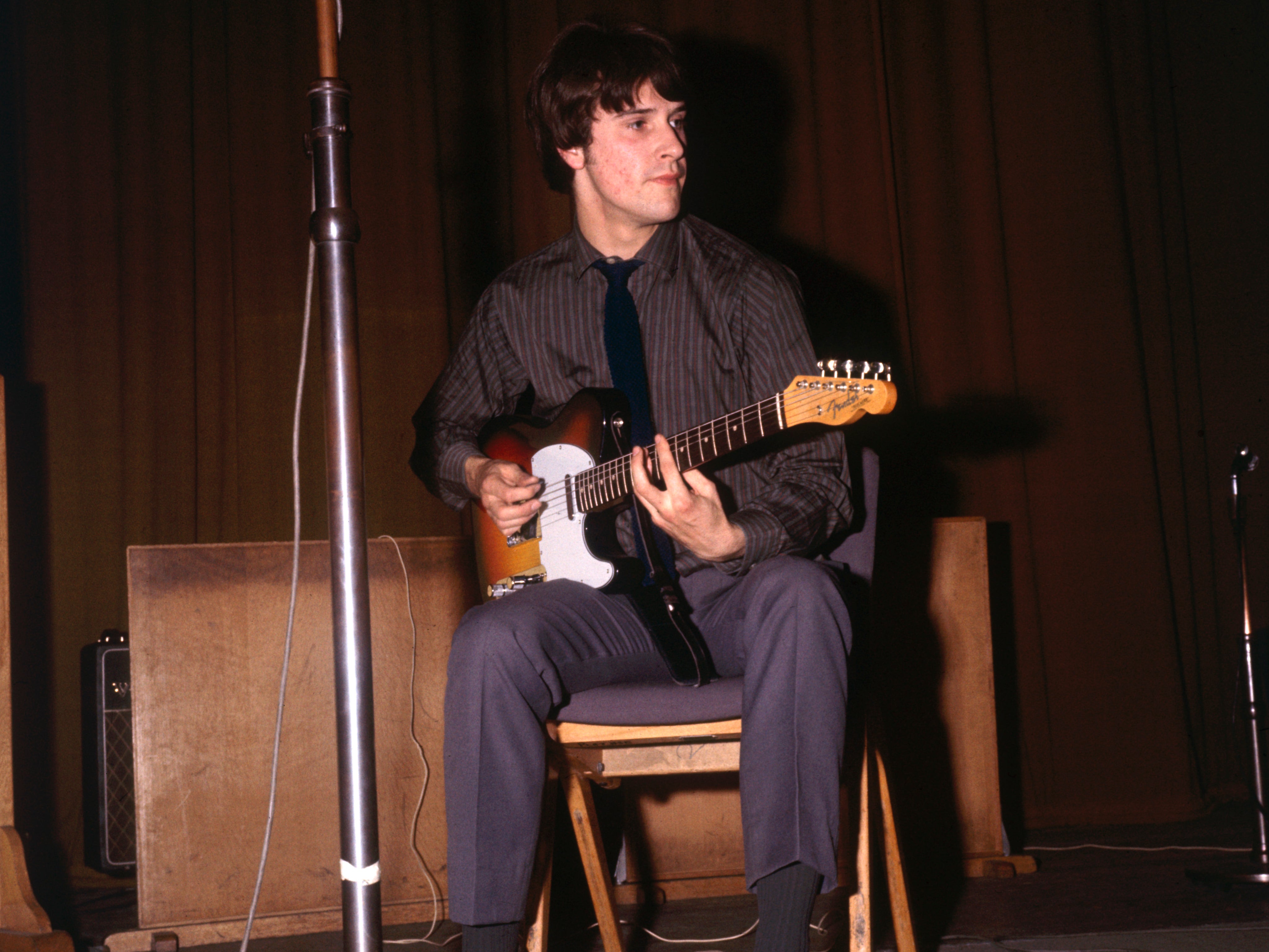

The Journey Pt 1, released in March, opened with the distorted power chords of “You Really Got Me”, the first great buzz guitar riff of the Sixties, created with an amplifier that lead guitarist Dave Davies had slashed with a razor blade. The single raced to No 1 in August 1964, and set the tone for primal rock riffs stretching way into the future, from “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” to “Purple Haze” and “Smells Like Teen Spirit”.

The Journey Pt 2 opens with the sharper, brighter, yet perhaps even more violent chords of “Till the End of the Day”, the guitar sound of The Jam’s “Art School” and “In the City”, as well as the ringing chimes of The Who and The Strokes. The song was recorded just over a year after “You Really Got Me”, at the beginning of November 1965, yet between those dates, The Kinks had released a stream of EPs and singles that included “All Day and All of the Night”, “Tired of Waiting for You”, “Set Me Free”, “See My Friends” and “A Well Respected Man”. Great songs were just pouring out of Davies – with “Dedicated Follower of Fashion” next to drop.

Then he had a breakdown. “People don’t realise how much pressure is on generally untrained musicians,” Davies says now. “I was learning as we went along. I think there’s a tendency to try to understand people’s emotional issues more now, but then they just said, if you don’t like it, go and be a dustman or join the army, or something.” Davies recovered, or as he puts it, “came up and wrote ‘Sunny Afternoon’”. It and the three latter singles mentioned above feature on the new collection, along with classic B-side “I Need You”, but The Journey Pt 2 ranges far and wide, all the way up to under-appreciated tracks from the mid-Seventies, when as Davies sees it, The Kinks went from “being a singles band into these sort of grand operatic illusions”.

Davies explains all of this in a gruff voice made gruffer by the tooth extraction he underwent hours earlier. The gauze still stuffed in his gums proves to be a further impediment as he very slowly articulates each word. I can’t see him either, so together we pick our way carefully forward.

How easy was it to agree on the tracklist with the surviving members of the classic line-up – his brother Dave, and drummer Mick Avory? (Bassist Pete Quaife, who left The Kinks in 1969, died in 2010.) “We all chose songs,” Davies says, and it became clear in the process that each of them had “quotes and memories and stories about the tracks. We did them separately,” he notes, “but it came out with a theme to it, very loose, and I wrote an accompanying narrative.”

That narrative describes a dark journey, in which the world of “the journeyman” starts to crumble as his life is turned upside down; he is “led astray by ghosts and a dark angel” and is seduced by “demons of the underworld”. Did it feel like a journey that Davies had lived? “Yeah,” he says, “the forces of evil around us all, innocence corrupted. It’s an odyssey of the band, primarily, and I was the journeyman.” His own innocence was at stake, though: “I have a dark side. I lived my songs.”

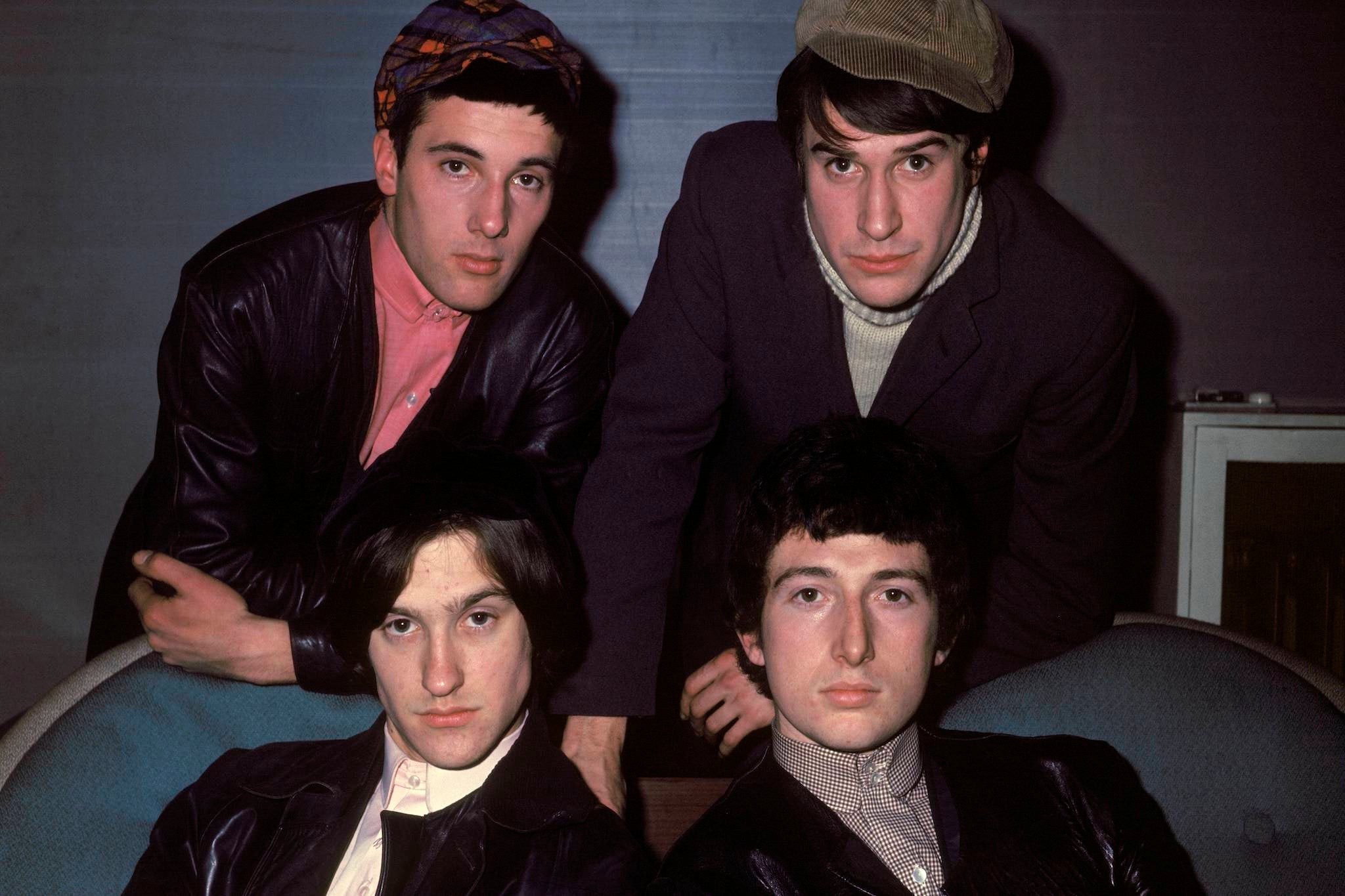

The Kinks formed in 1963, when Davies was a 19-year-old art student and his younger brother, Dave, on the cusp of 16. They were the youngest siblings, with six elder sisters, from a large family in Muswell Hill, north London, where both attended the local secondary modern school. After the release of “You Really Got Me”, fame arrived quickly. Dave, who was just 17 when the band became pop stars, threw himself into its excesses and became a living embodiment of the Swinging Sixties. As his younger brother explored the wild side of stardom – booze and drug binges; sexual relationships with men and women – Ray settled down, marrying Bradford-raised, convent-school girl Rasa Didzpetris and starting a family.

Their asymmetrical lifestyles created tension. It’s been suggested that the 1967 song “Two Sisters”, included on The Journey Pt 2, with its “she was so jealous of her sister” refrain, is really about the two brothers. “Oh yeah, both got handbags,” Davies quips, before he admits, “There’s an element of that in it.”

There had been early complications in the brothers’ relationship. “I didn’t live with Dave all the time when I was growing up. I lived with my sister, there was no room for me in the house.” This last line is delivered with a melancholy that suggests he still feels it. “We have a relationship, that’s for sure. I try not to be too judgmental.”

My relationship with David is like Raging Bull, and the dynamic between the two brothers in that movie. It’s violent but loving

It’s not hard to see the dynamic between them shaping the early sound of The Kinks, the tension between an introspective, sensitive soul with an extrovert, confrontational force. “It’s like Raging Bull, and the dynamic between the two brothers in that movie. It’s violent but loving,” Davies says. His brother’s sometimes extreme recklessness – he was considered as wild and unpredictable as Keith Moon – led to an incendiary incident on stage with drummer Mick Avory in 1965. The two had been friends and flatmates, but when the guitarist kicked Avory’s drums over during a gig Cardiff and told him, “Why don’t you get your c*** out and play the snare with it? It’ll probably sound better,” the latter hit him with his drum pedal, leaving Davies bloody and unconscious, before fleeing the crime scene, with Ray reportedly screaming, “You’ve killed my little brother.”

“The police wanted to do Mick for attempted murder,” Ray said many years later. “It really had a tremendous emotional effect on me.” In the end, stitches were applied, charges were not pressed, and somehow the band patched things up and carried on. “My eldest sister Rose said, ‘I know you’ll always look after David, no matter what he does,’” Davies tells me. “I’ve still got that feeling. There’s a telepathy between us. I frowned upon him for a while. But there’s an acceptance.”

How does he feel about the fact that so many of his peers in the Sixties rock scene didn’t make it out the other side, from Brian Jones to Jimi Hendrix to Brian Epstein. “Death, you mean?” he says. “I don’t know, it was a drug-filled culture at the time. I must make a confession, you know: I never did drugs. I’d done all my drugs when I was an art student [at Hornsey art college]. There was a pressure on people’s lives then, because it was a new, exciting world and you could try everything. Brian Jones was a great guitar player and a wise head. I don’t know what Brian Epstein’s problem was but it’s tragic.”

Does he feel like a survivor from that period? “They all had their time,” he says, dispassionately. The subject, though, reminds him of a song from The Journey Pt 2 – “Where Are They Now?” – which is taken from the 1973 concept album Preservation Act 1. That LP had been Davies’s despairing response after Rasa left him. On stage in west London in July that year, he’d kissed his brother on the cheek and told the crowd, “I just want to say goodbye and thank you for all you’ve done.” Hours later, he was admitted to hospital, having taken an overdose of antidepressants. He later confessed he’d attempted to take his own life.

Rasa was very loyal and supportive – when I wrote many of those songs, I was impossible to be with

Davies looks back on that time “with great difficulty”, he tells me. “My world fell apart a bit. My natural reaction was I had to write something.” He has always been able to turn to music when things get overwhelming; to “pour out all your emotions on a piece of paper and write what takes your fancy. It’s therapeutic and cathartic. I probably wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for the songwriting”.

I tell him that in an episode of the brilliant podcast A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs, writer Andrew Hickey suggested that Rasa may have been more important to Davies’s songwriting than is generally acknowledged, contributing ideas and perhaps the odd line in addition to backing vocals, such as the sweet “sha-la-las” on “Waterloo Sunset”, while ever present in the studio for long parts of the band’s golden era. “She was very loyal and supportive,” Davies says. “You know, when I wrote many of those songs, I was impossible to be with. And she sang backing vocals. I liked the sound of her voice with Dave.” He won’t go as far as co-writer though, “It’s a nice idea, but it was basically down to me,” he says. “I was writing all the songs, finishing them in the studio; [Rasa] was very supportive.”

Had he felt left by his brother with the burden of writing the songs to keep the show on the road, while also coping with the responsibility of being a young husband and father to two daughters? “No, it helped me write some of these characters,” he says. “We were on the road all the time. I wrote ‘All Day and All of the Night’ in a car going to a gig. My writing suited this lifestyle.” The pressure was intense, though. “If a record came out and went in the Top 10, as soon as it dropped, the phone calls came: ‘We need another single.’ ‘All Day…’ was requested and we had the record made in a couple of days.”

In the 1980s, after his split from Rasa, Davies found himself one half of a famous rock ’n’ roll relationship with The Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde, who had covered one of The Kinks’ early songs (“‘Stop Your Sobbing’ is a great cover,” he notes). “The couple had a daughter, Natalie, together but their tempestuous romance couldn’t last. In her memoir, Reckless, Hynde described how they almost wed in Guildford in 1982, but “the guy in the registry office took one look at us and suggested we come back another time. I guess the mascara smeared all over my face was the giveaway.”

“The pressures surrounding that sort of relationship are immense,” Davies says now. “Paparazzi pressure and pressure within the bands. Both bands reacted negatively. It’s destined for failure, but people keep trying.” When he looks at famous rock star relationships like Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham, which became a similar powder keg, he wishes them well, he says. “I don’t want it to end in failure, [but] it’s inevitable. I’m trying to think of a couple that are still together after all these years.”

Davies married again, to Irish ballet dancer Patricia Crosbie, and had another daughter, Eva. He and Crosbie split after 13 years, and Davies has spoken in the past about how that time of his life, around the turn of the millennium, was particularly boozy as he turned to drinking because he felt so isolated. Is it hard when you’ve had great fame to return to normal life? “I don’t think if I tried to, I could live a normal life”, he says, “because I’m too normal.”

This is the sort of gnomic witticism that flows naturally from one of rock music’s defining poets. A droll humour underpins Davies’s conversation – The Who, he notes, “made a very wise choice copying The Kinks”; “God’s Children”, from the unrealised rock opera Percy, was “my protest song about penis transplants”; the best band of the Sixties was an unknown bass, piano and guitar trio – “We played at my art school dance.”

He laughs when I repeat his “too normal to live a normal life” line back to him, but there’s an underlying seriousness. “People expect me to be a champagne man and all the accessories. But really, I’m just a poor sod.” An influential one, though. Film director Wes Anderson likes The Kinks so much that he considered filling his 1998 film Rushmore entirely with songs by the band but settled for “Nothin’ in the World Can Stop Me Worryin’ ’Bout That Girl” from 1965, then used three songs from the 1970 LP Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One in 2007’s The Darjeeling Limited. “I was at the preview of that film,” Davies notes, “and he said, ‘Thank you’, and I said, ‘Pleasure.’ That’s all we said.”

I think it’s good that people with no real voice have been able to find their identities.

Two of those songs, the yearning “This Time Tomorrow” and “Lola”, are included on The Journey Pt 2. The latter, about a romantic encounter with a transgender woman, made the US top Ten (and Rolling Stone’s 500 greatest songs of all time). I wonder what Davies makes of how divisive the issue has become more than 50 years later. “I think it’s good that people with no real voice have been able to find their identities,” he says. “Honestly, I think so much muck comes up with it. People questioning everything.”

Well, what are his thoughts? By way of an answer, Davies quotes the “Girls will be boys and boys will be girls” line from the song. “It’s a wide, beautiful world and people should have the right of choice,” he says, before adding diplomatically, “Conversely, people should have the right to state their opinion.”

So what next for The Kinks? “Any time we’re in a room together is a very rare occurrence, but I wrote a little play that was performed at a local theatre [one-man show The Journey Pt 1, starring actor Ben Norris, played in Hampstead village earlier this year], and we all went to that. Both my brother and Mick were smiling so they must have enjoyed it.” By this late stage in the band’s career, he and Dave have reached “a place of calm”, he says. “We were talking yesterday, and he’s still got things he wants to write, so we’re gonna audition some of his new stuff.”

This is intriguing. Davies talked up the possibility of a Kinks reunion in 2013, and again in 2018, but neither happened. Is there a chance they might finally get together and work on new material? “I’d like to – depends how it shapes up,” he says. “If we do, it’ll be very different to anything we’ve done before. You know, the capabilities of what we can do now, we’re not gonna go on tour with it. I don’t want to do the conventional scenarios any more.” Does he mean finding new ways to express the songs he’s got in his head? “I wouldn’t call them songs, I’d call them more events,” he says. “Little events structured together. We’ve got to be realistic with what we can achieve,” he adds. “You have to think practically.” He seems to feel he’s too old to tour now, although inside he still feels like “a kid waiting for the van to come and pick us up for a gig”, he tells me.

Does he contemplate his own mortality? “Now and again,” he says. “The parting will be painful. You know, I’ve got four lovely daughters, and grandchildren. And for them, the people you leave behind… But I’ll keep writing songs as long as I can.” He wrote the theme song for Jimmy McGovern’s Broken a few years ago. McGovern has said that on arrival at the pearly gates, he will be carrying the screenplay for Hillsborough under his arm. What, I wonder, is Davies most proud of? “Gosh, that’s really…” he begins. “I’m not proud of anything the most.” He pauses. “I try not to be too attached to anything. People are important.”

‘The Journey Pt. 2’ is out now via BMG

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks