The Kinks’ Dave Davies: ‘Ray and I have spoken about a reunion – it’s possible!’

The groundbreaking guitarist talks to Kevin E G Perry about reuniting the iconic band with his brother, relationships with men and women during the swinging Sixties, and his viral tweet about pubic hair

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In his new tell-all memoir, Living on a Thin Line, The Kinks guitarist Dave Davies writes movingly about his recovery from a stroke in 2004, his fractious relationship with elder brother and bandmate Ray, and his own years of rock star excess. Tabloid coverage of the book has, however, tended to focus on just one aspect. “Dave Davies: Aliens banned me from having sex,” ran a recent headline in the Toronto Sun, proving that you can be as candid as you like about your life, but mention just one alien sex ban and it’s all anybody wants to talk about. “F***in’ hell, it’s a cheap gag isn’t it?” says 75-year-old Davies, chuckling good-naturedly. “It’s like taking your trousers down to get a laugh.”

The curious incident in question occurred in 1982 at the Sheraton Hotel in Richmond, Virginia. Davies was on the road with The Kinks, the revolutionary British rock band he’d co-founded two decades earlier, when he began to hear otherworldly voices communicating via telepathy. “What you’re about to read might sound a bit crazy,” writes Davies in Living on a Thin Line. “I called these voices ‘the intelligences’ and I realised they had taken over complete command of my senses.” Among the messages he received was an instruction not to have sex. “The reason being, they told me,” writes Davies, “was they wanted to transmute my sexual energy to a higher vibrational level.”

Davies is well aware that this doesn’t sound entirely rational, but that’s sort of his point. Speaking over a video call from London, looking bohemian in a black beanie and red-rimmed specs with a string of beads slung around his neck, Davies makes the case for exploring the irrational and the unconscious mind. “Life can be hell for really sensitive people,” he says. “We have a hard time trying to work out what the f*** is going on, on a day-to-day basis. We have to formulate some kind of imaginative concept just to put our bleedin’ shoes on! What is this madness? Carl Jung spent all his life trying to work out what the f*** is going on in there, and he realised that we haven’t even begun to understand the mind. We can’t be afraid of new ideas. That’s what art is for!”

Like so many other sensitive young people, Davies found salvation in art. Born in Fortis Green, north London, in 1947, he was the youngest of eight siblings: six sisters and brother Ray. “You have to remember,” he says, “that Ray and I grew up in a matriarchy.” Some of his earliest memories are of Saturday night knees-ups in the front room, where his extended family would gather to drink beer and play music. “It seemed like everybody knew how to play the piano!” he says with a laugh. “It was a big, working-class family, so it was quite a houseful at the weekends. They were the generation who lived through two world wars, so they made their own entertainment.”

It was in the front room, in March 1964, that musical history was made. Davies was 17, a science fiction-obsessed teenager who liked to tinker with electronics to “make silly things that didn’t make any sense with bits of wire”. He’d recently bought a little green guitar amp for the princely sum of £10, which one day in a fit of hormonal angst he’d set upon with a single-sided Gillette razor blade. “I’d had an argument with my girlfriend and I was full of rage and pissed off,” Davies remembers. “Rather than slash me wrists, I thought I’d attack the speaker cone. I sliced the cone down, virtually all the way around, and was quite surprised that it was still working. It had this kind of raspy sound, and I liked it.”

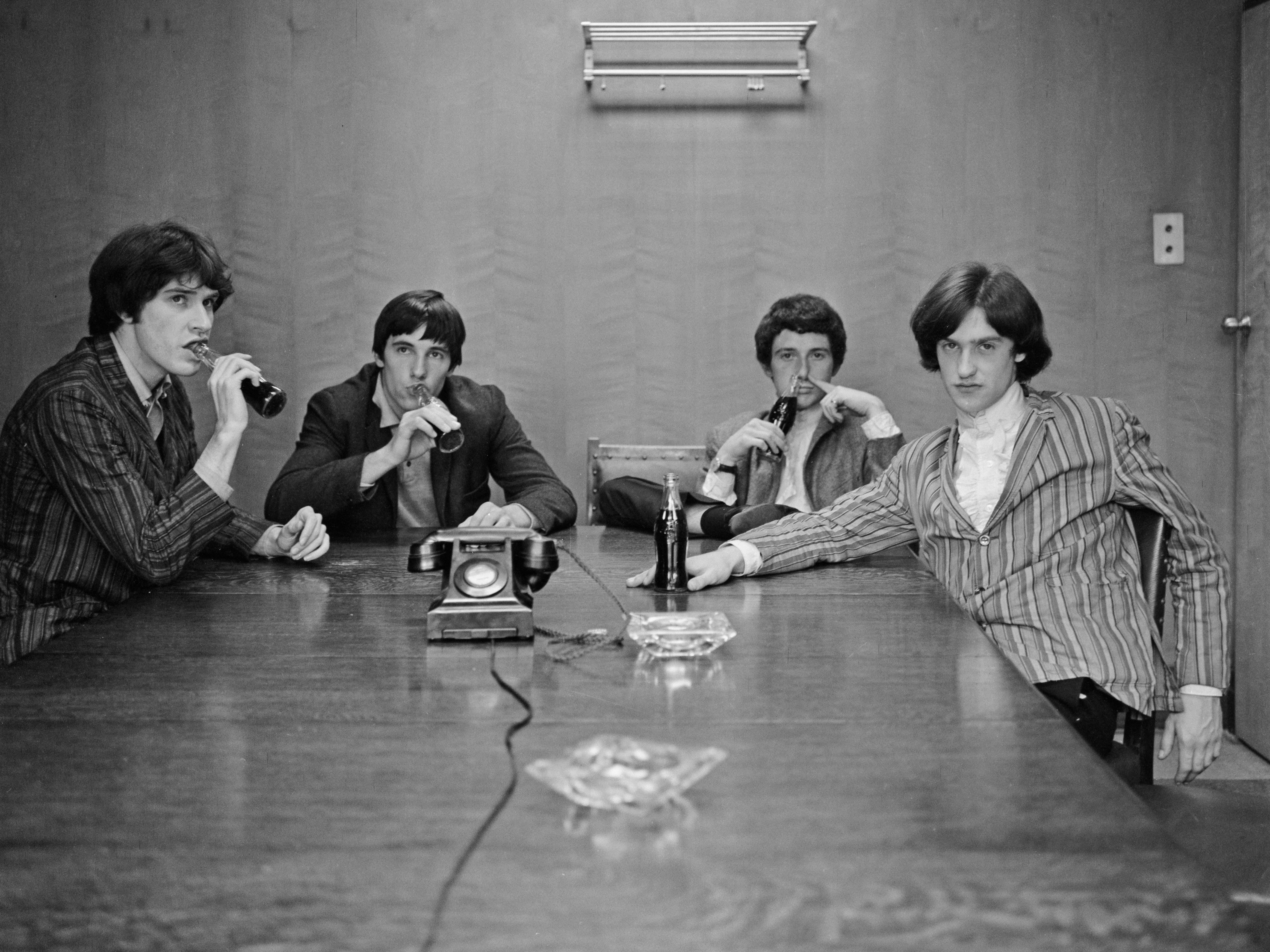

At the time, the Davies brothers had already formed a band with their friend Pete Quaife on bass, and Ray had begun writing songs on the family’s upright piano. “He wrote the ‘You Really Got Me’ riff on that piano,” explains Davies, “I tried it with my new sound and that’s how we really started.”

Music, fashion and silly hats; it’s all part of this incredible period in history when we lifted the lid on society

The distorted power chord that reverberated out of Davies’s guitar would transform rock’n’roll. Generations of musicians, from The Who’s Pete Townshend to Tom Petty, credited it as a seismic influence. Jimi Hendrix told Davies he considered the song a “landmark record”, and Van Halen covered it as their debut single. In that moment, however, it was only the two Davies brothers who had heard it. “I thought it was amazing,” says Davies, smiling with pride. “I felt more like an inventor. Some people adored the sound, and others hated it, but once we put it into the context of the song Ray was writing it started to become what it became, which was a phenomenon. It was a phenomenal time anyway. It seemed like the working class was really breaking through with art and movies and music.”

Released in August 1964, “You Really Got Me” quickly rose to the top of the charts. Together with follow-up “All Day and All of the Night”, it catapulted The Kinks to the heart of London’s Swinging Sixties pop scene. “It seemed like you could do anything, say anything, wear anything,” recalls Davies. “That’s why I got into fashion, because I found it to be a perfect way to express yourself. Music, fashion and silly hats; it’s all part of this incredible period in history when we lifted the lid on society.”

Davies was soon a regular fixture at London club The Scotch of St James, where he’d hang out with the likes of John Lennon and The Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones. “Every night was party time,” says Davies. In Living on a Thin Line, Davies writes candidly about his “rapacious desire” for women as well as his relationships with men, including an “intense affair” with Michael Aldred, one of the presenters of music show Ready Steady Go!. Although Davies remembers the era as one of great personal freedom, he also knew wider society still hadn’t caught up. “Homosexuality didn’t become legal until ’67,” he points out. “But I suddenly realised that there were a lot of gay people in the music business. At school I didn’t think it was even possible! This whole new world had opened up, but because being gay was illegal it was very private. It became quite a common thing to go to parties where people were experimenting with sex. It wasn’t a free-for-all mad orgy, but you could express the way you felt a lot easier at that time.”

He worries, he says, that young people today don’t get to experience a similar sense of freedom. “I’m not sure we’re on the right track,” he says. “I’ve got sons of my own, and it’s f***ing difficult growing up. The pressures on young people are probably more than ever, certainly more than when I was leaving school.” These days, he says, there’s a greater sense of being watched and judged because “these Orwellian complications have entered into our lives”. Davies got a taste of that himself in December last year, when a tweet of his went viral to much outrage and consternation. He’d written: “I’m not sure if this is an appropriate tweet but in the Sixties some of the models shaved their minges. I always thought it was a turn off. I always liked women to look ‘au naturel’.” Davies does a high-pitched impersonation of a shocked matron as he recalls the response. “Oooh you can’t talk about pubic hair!” he trills. “Nobody has pubic hair any more, it’s not allowed. There’s been an act of parliament!” He shrugs. “It’s just language.”

By 1967, at the tender age of 20, Davies was already starting to feel burnt out by The Kinks’ fame and relentless touring schedule. As had become something of a Davies tradition, he went home to write a song on the family’s upright piano. The song, “Death of a Clown”, was released as Davies’ first solo single, although it was also included on The Kinks album Something Else by The Kinks. It captures Davies’ increasing weariness about the non-stop party scene that had become his world. “I felt like a bit of a clown living the party life,” he says. “It gets you down after a while. You realise, what the hell am I doing? Why am I buying drinks for all these people? When you get to writing and thinking about life... it’s fun, but there’s a lot more to life than just that. Life can be fun, but it’s also quite a serious endeavour.”

By the end of the Sixties, The Kinks were maturing as a band. Records such 1968’s The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society and 1969’s Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) weren’t just a showcase for Ray’s evolving songwriting; they were an examination of what it means to be English. “The Village Green Preservation Society,” writes Davies in Living on a Thin Line, “was about an England that did exist or never existed, or may exist in the future.”

Over half a century on, questions about the nature of Englishness have only become more pertinent in the era of Brexit and Etonian rule. Davies remains fiercely proud of where he’s from. “I’m glad I’m English, and that I was born on these islands,” says Davies. “I’ve taken a great inspiration from my own working-class culture, and the comedians and politicians who came from it. I’m not a great political person, but I think it’s a system that has gone a bit wonky. We need to develop, somehow, more refined spiritual concepts about where we are and about the universe. We’ve got this incredible gaping universe right in front of us, and we’re lying to each other and playing terrible silly games. I found that out when I first took acid, which lets you see through this stuff. Do we really want a life full of lies and s***?”

Davies wrote and sang about his own vision of Englishness on The Kinks’ 1985 single “Living on a Thin Line”, which gives his memoir its title. By then he was starting to worry that the group were little more than Ray’s backing band, so poured his feelings about how their relationship had become an uneasy tightrope into lyrics ostensibly about the decline of England. “Now another century nearly gone,” sings Davies. “What are we gonna leave for the young?” The song has become one of the band’s enduring hits, and was famously used repeatedly to great effect in the 2001 Sopranos episode “University”. Davies is justifiably proud of the song. “‘Living on a Thin Line’,” he says, “is about us.”

Although The Kinks never formally split, the Davies brothers’ relationship continued to deteriorate until the band played their last show in 1996. Each continued with their own solo careers, and there were signs of a rapprochement in December 2015 when Ray joined Dave onstage at London’s Islington Assembly Hall to roar through “You Really Got Me”.

In two years time it’ll be the 60th anniversary of that world-changing single, and Davies says that like fans all over the planet he’s keeping his fingers crossed that it could prove the perfect occasion to get the band back together. “I hope so! I do,” he says. “Ray and I have spoken about it – it’s possible!” The pair were photographed together on the streets of north London enjoying a Christmas Eve beer during lockdown in 2020, and Davies says that after years of tense sibling rivalry their relationship is on the mend. “We get on okay,” he nods. “We talk about football! We’re born-and-bred Arsenal fans… So, yeah, I’m optimistic about the future.”

To my surprise, it’s a lyric from 2016 jazz drama La La Land that Davies recites to sum up what he’s learned from almost six decades of rock’n’roll. “A bit of madness is key/To give us new colours to see,” he quotes. “I grew up in the music business, and it’s insane. We have to touch madness to draw from it, and it stimulates us as well as driving us mad. Maybe real truth is inside that madness somewhere.”

‘Living on a Thin Line’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments