The funky legacy of Grace's island

As disco died in the late Seventies, no one saw a Caribbean backwater as the new home of dance. Then Ms Jones, and Sly and Robbie, came.

The Bahamas is generally not seen as the musical hotbed of the Caribbean. It hasn't produced a Bob Marley, David Rudder or Rihanna. However, 10 miles west of the city of Nassau, on New Providence, one of the 29 inhabited islands in the Bahamas, lies Compass Point. It's a string of huts and cottages painted lavender, teal and tangerine, overlooking two coves bordered by white sand.

Opposite the tiny resort is Compass Point Studios. It was here that some of the most progressive, idiosyncratic dance music of the Eighties was made, a body of work that has more than stood the test of time. A new compilation, Funky Nassau: The Compass Point Story makes this very clear.

While Grace Jones' "My Jamaican Guy", Tom Tom Club's "Genius of Love" and Gwen Guthrie's "Padlock", tracks that have filled floors from New York to New Zealand over the years, are obvious highlights, other cuts, rarities like Will Powers's "Adventures in Success", are stand-outs too.

The studio was the vision of Island records boss Chris Blackwell, the man who brought Marley to the masses in the early Seventies. He dreamt of a recording complex "in a restful location" to pursue new projects, and no place fitted the bill better than one and a half acres of oceanside land in a Bahamian hideaway.

It was in 1977 that construction of the studio got underway. Everything was state-of-the-art; songs were recorded on a 24-track unit and the mixing desk was a MCI 500; Blackwell initially built one room, Studio A, but because artists were clamouring to record, a second room, Studio B, was added shortly afterwards. Initial sessions were booked by the likes of Dire Straits, the Stones and Roxy Music, but they didn't really put Compass Point on the map as a studio with a signature sound.

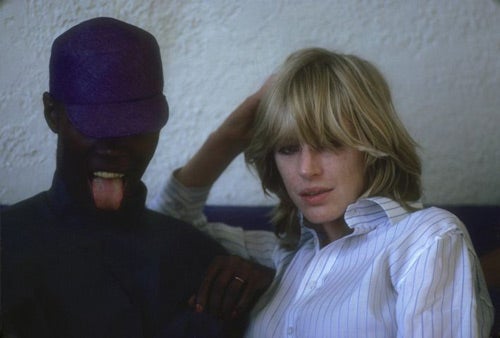

The artist who did that was Jones. The daughter of a Jamaican preacher who had worked as a model in Paris and New York in the Seventies, Jones reinvented herself as a singer with an outrageous, androgynous look at the dawn of the Eighties.

While her fearsome flat-top haircut and men's suits turned heads, Jones's early records like Portfolio had precious little artistic coherence. Signing her to Island, Blackwell handpicked a studio house band that would include a "Jamaican rhythm section with an edgy mid-range and a brilliant synth player" to work with her, to make music that suited her. So was born the Compass Point sound.

Anchoring the combo were the drummer Sly Dunbar and bassist Robbie Shakespeare, arguably Jamaica's finest groove merchants, and who had played with anybody from Lee Perry to Peter Tosh. So telepathic was their chemistry that they were dubbed the "riddim twins". While their compatriots, guitarist Mikey Chung and percussionist Uziah "Sticky" Thompson, also a member of Tosh's band, kept the Caribbean flavour strong, the urbane English guitarist Barry Reynolds, once of oddball British blues-rockers Bloodwyn Pig, was also drafted in. Arguably the trump card was the Ivory Coast keyboard maestro, Wally Badarou.

Behind the mixing desk was a brilliant American engineer, Alex Sadkin. He was a man so meticulous he could spend as long as four hours setting up Dunbar's drums in order to capture every fluttering high frequency and sub-sonic blast as the tapes rolled.

The fruit of their labour was a strange, saturnine blend of reggae, funk and rock with Jones's glacial, menacing voice sitting perfectly on grooves that were both muscular and sensual. Many of the songs were dance numbers but they had none of the sagging grind of the last days of disco. Texture, tempo and pulse were all imaginatively manipulated.

Sly and Robbie often played tight, sparse lines, while Thompson laid down a frenetic cowbell pattern to give the impression that the head of the music was jerking frantically while the body sexily moonwalked down below. Jones's "Pull Up to the Bumper" was the epitome of this polyrhythmic pinball beat.

Then there was the input of Badarou. He was essentially to the Compass Point Band what the great Bernie Worrell was to Parliament, and contrived to produced all those fizzing, syncopated synthesiser sounds that brought a space-age tingle to the mix, which was given an eye-of-the needle precision by Sadkin.

Over time the team expanded and another significant figure – the Jamaican engineer-keyboard player Steven Stanley – joined the fold. The players were encouraged to be adventurous. Many Compass Point sessions yielded music that chimed with New York's "No Wave" scene, the hybrid of punk and disco.

Apart from the scary posters of Jones on the walls, there was, by all accounts, nothing remarkable about the studio itself. What gave it something special was the paradise-like setting, its "restful" location and the relaxed atmosphere.

For example, when Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth, both members of Talking Heads, cut tracks at Compass Point as Tom Tom Club, the group created magic through the input of studio staffers. On the funk classic "Genius of Love", Stanley supplied the robot-like synth licks, and Sly and Robbie popped in to provide handclaps because they were in an adjacent studio.

Similarly, Ian Dury and his pianist-writing partner Chas Jankel flew in at Blackwell's request and ended up playing with the Jamaicans to produce the controversial, and banned, "Spasticus Autisticus".

Even more fortuitous was the session with a brilliant New York vocalist, Gwen Guthrie, who met Sly and Robbie in the city when they were looking for vocalists to work on Peter Tosh's Bush Doctor album. She was Aretha Franklin's backing singer. "Padlock", a piece that set Guthrie's surging lead vocal to a tough Sly and Robbie beat would become a massively popular track in New York clubs, and in many ways perfectly captures the cosmopolitan pedigree of the whole Compass Point music machine. Unfortunately, towards the end of the Eighties, cocaine started to ravage the Compass Point staff. Chris Blackwell spent more time overseas, some dodgy business went on the books and Alex Sadkin was killed in a car crash. Recording sessions eventually stopped.

Blackwell would re-activate the studio in the early Nineties, but there has been no attempt to re-assemble the house band.

As the Funky Nassau compilation shows, their musical legacy is a rich one. It grew out of specific conditions: a record label boss willing to take risks and allow musicians to create spontaneously was one thing. The fact that in the early Eighties there was less stratification in the music industry was another. Moreover, nobody saw it coming from a studio in the Bahamas next to a few lavender, teal and tangerine cottages.

'Funky Nassau: the Compass Point Story' is out now on Strut

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks