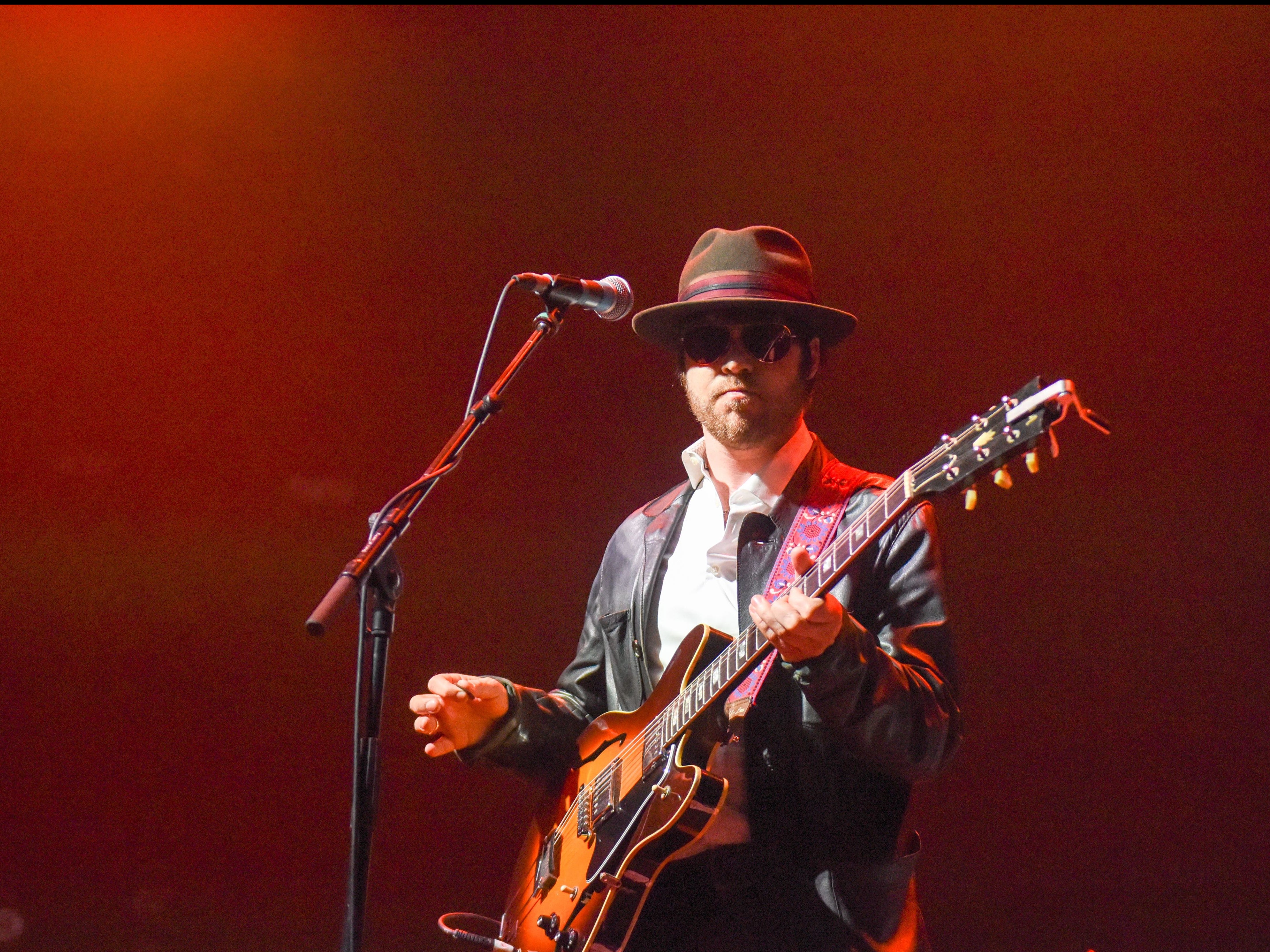

The Coral: ‘People are tricked into believing that tiny thing called the mainstream is everything’

Michael Hann talks to the band who shot to fame in the Noughties about their glorious new album, why there’s only space for one or two groups in the mainstream, and how once you turn your back on that type of fame, you can’t really get it back

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There’s something about a tattered seaside resort, where the smell of vinegar and beer hangs heavy on the front, and the air is alive with the sounds of yapping gulls and the rattle of the penny cascades. “It feels like you’re at the edge of the world, doesn’t it?” says James Skelly, the lead singer of The Coral. “There's nothing beyond it as far as you can see; I became obsessed with old photographs of New Brighton and Llandudno and places like that when they were in their heyday, and when I'm there, I'm imagining what they were.”

You might say the notion of seaside towns as ramshackle but adored places whose days of glitter and glamour are behind them is an apt metaphor for The Coral. After growing up in Hoylake, on the western side of the Wirral peninsula, they found sudden and unexpected success with hit singles such as “Dreaming of You”, “Pass It On” and “In the Morning”, songs that were timeless, connected as much to the pre-rock’n’roll era as to the other Merseyside guitar bands who emerged at the start of this century – The Zutons, The Dead 60s, The Little Flames, The Stands. They were Mercury-nominated for their debut album; they seemed set to be the next big northern guitar band after Oasis. And then they weren't.

Nick Power, The Coral’s keyboard player, might be talking about his own band, then, when he talks about seaside resorts. “They’re totally marginalised places. England seems to want to write them out of its history. I think it's ashamed of them. So then that creates a sort of outsider thing, where the people who we don't want to see on the front pages of our magazines and newspapers congregate, but then they're the most interesting people a lot of the time. A lot of good ideas come from those fringe places, because you're left alone. They don't care about adherence to any notion of what's acceptable.”

Hence children learning to gamble on the penny cascades, frittering away copper after copper. Hence the food. “Yeah, you’d never sit in your house and just eat a stick of pure sugar, would you?” Skelly says.

The Coral have been spending a lot of time at the imaginary seaside. Their 10th album, Coral Island, is a double – with narrative interludes by Skelly’s grandfather – loosely themed around the notion of the seaside as the place where everything can be explored. “It started off when we drove past Coral Island in Blackpool after we'd done a gig,” Skelly says, “and it triggered the idea for a place, a banner where all our separate ideas could come together. Then it started to develop into something else – in my head it started to become like an HBO series, or The Prisoner. It was this mythical seaside place where you went and you could never leave, but it didn't exist.”

It’s a glorious record, both sunny and cloudy. Sometimes its waters are warm and clear, sometimes murky and chilly. It nods to The Coral’s musical touchstones – variously identified by Skelly and Power as Joe Meek, Del Shannon, the Everly Brothers, Liverpool music, rock’n’roll and Texas psychedelia – and still sounds like, well, The Coral: defiantly English, creators of their own world. “If you know music, I think you know where little bits come from,” Power says. Nick Cave and Tom Waits, he points out, always end up sounding like themselves, no matter how much they have borrowed from others.

Coral Island is the highpoint of an unlikely career renaissance for The Coral. They came together as teenagers 25 years ago; close enough to Liverpool to be drawn by the gravitational pull of that city’s music, but not quite of it. They were still little more than kids when they released their debut album in 2002 and went top five, then followed it with a No 1, Magic and Medicine. And then they took their toys, and threw them out of the pram with the record Nightfreak and the Sons of Becker, very much their Captain Beefheart album.

They didn’t realise what they were doing at the time, but Skelly and Power both recognise that record now as their call for help. They had become suddenly and unaccountably successful – no one could have predicted that a group mixing sea shanties and psychedelia and pre-Beatles pop would have captured the public imagination so thoroughly – and they had no idea how to deal with it. Skelly remembers telling Alan Wills of Deltasonic – the label that released their albums, through Sony – that he’d be happy selling 30,000 copies of their debut, as The Beta Band – likeminded psychedelic travellers – had of their compilation The Three EPs. “And then suddenly it just went off. And I just don't think we have the infrastructure to deal with it.”

“I think I was so deluded that I thought people on tennis courts” – I have no idea why Power picks tennis courts – “would listen to Nightfreak. There's something about being big in that way where people are projecting their image of you back onto you. And I was never comfortable with it. I think that's what fame is. People projecting something in their mind onto you that isn't necessarily you. It was self-sabotage, definitely.” Though Nightfreak was followed by more hit albums, something had changed irrevocably within the band – they had been burnt by their proximity to real success (“It feels like you're not yourself,” Skelly says. “And I think at some point, I did make a decision that I would rather have myself back”) – and eventually it would cause them to force themselves into a complete reset.

They talk about those first few years of success with a degree of ambivalence. On the one hand, it drove them to the edge. On the other, what’s not to love about being in a band whose every gig is bigger than the one before, and who are constantly hailed as geniuses? “I think I took it for granted,” Skelly says. “I was young, arrogant, smoked way too much weed. And so in a way you're riding on it. I was 21 and was going, ‘I want this.’ Then you get there and go, ‘Do I want it?’ You're so young. I don't think anyone knew what was happening. And I don't think you can even make sense of it now. You just have to go, ‘It happened. It was great. I had a laugh. And now I'm here.’”

“I could barely do an interview at 21,” Power says. “I was still living in my mum's. And smoking about 40 quid’s worth of skunk a day. It was stupid. We didn't really even have a manager. No one said to us, ‘Just knock that on the head for a bit, go for a run and get your hair cut, and you'll feel better.’” He starts sounding like the parent he has recently become. “You know, them little things are important: ‘Eat three meals a day! You've got three cold sores on your lip!’” In retrospect, he says, “I think we wanted out too quickly.”

The first to get out was their brilliant guitarist Bill Ryder-Jones, who went on hiatus, then left for good. “At that point, really, that version of The Coral was over,” Skelly says. “And then you're in a trance, sort of in purgatory, just kind of trying to make things work within that. But we weren't all pulling in the same direction.”

By 2012, when the band went on a four-year break, Power says, “we had nothing left to say. We didn't know why we were doing it. We didn't know what kind of songs to write or what we meant to people. We didn't have any connection to our fans, which we do now. We were just bored. We all went away and found different outlets, so when we came back it was like a new band.”

Coral Island will be their third album since their return in 2016, but now The Coral face a different issue: how to be a band that never gets any bigger or any smaller. All three albums have been excellent, but The Coral are now in that position that many bands find hard to cope with: being a part of the furniture. Power notes that lots of bands start to struggle immediately after their first album, because having invested all their hopes in that one record, and having ridden that wave of excitement, they realise nothing will compare to it, and life from here is just paddling frantically to maintain position. “You quickly learn that there's only space for one or two of you in the thing that we call mainstream. And then when it gets taken, you can't really get it back. But it's a lesson. I think people are tricked into believing that tiny thing called the mainstream is everything, when a lot of my favourite records and things growing up, and films and everything, were not in the mainstream.”

For Skelly, contentment has come in the simple act of writing songs. “When you're younger, you're more idealistic, but when you get older, you do become more pragmatic about it,” he says. And getting older has taught him to be more accepting of the lows. “You accept that you're not going to be happy and fulfilled all the time. The Coral is like a brotherhood. I think at one time, it was probably a cult. You get older, and for most people it's difficult to spend time with your friends. So we still get to do that and get paid for it. You have to look upon it in that way.”

Power uses the same phrase to describe their early days. “When we were younger, we were like a cult. We were five or six days a week in each other's company in a windowless rehearsal room on the Dock Road in Liverpool. And that was the mission. When you achieve it, that's when the confusion sets in. Because you've been working on it for five to six years. But when you achieve it, you think, ‘What the f*** do I do now?’ But now we can turn up to a studio separately and leave separately. It used to be: everyone in the van to the studio, leave at the same time. We were just in each other's pockets.”

He considers their current place in pop’s giddy firmament, and laughs gently. “We’re a band that writes double albums about decaying seaside towns. So maybe we’re at our right level. I don't think we should be massive. But we make a living and it's good and I get to do art every day. So there's nothing to complain about.”

Coral Island is released on 30 April on Run On Records

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments