Why are we still obsessed with finding ‘secret’ messages in Beatles songs? How The Fab Four accidentally invented the music conspiracy theory

Conspiracy theories and rumours about ‘secret messages’ reportedly hidden in songs by The Beatles have persisted for more than 50 years. Why?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As long as there has been music there have been rumours about “hidden messages” inside it.

But no band has inspired more urban legends than The Beatles, who despite breaking up more than 50 years ago, are still fuelling books, internet forums like Reddit, as well as article after article about supposed “secrets” buried in the lyrics, album art and recordings of more than 200 of their songs.

What is it about the Fab Four that interests conspiracy theorists so much?

It all started back in 1966, when they were recording their Revolver album and discovered “backmasking”; the process of recording a message that can only be heard when listened to backwards.

It had been around since the late 1800s, but was popularised by the band in the 20th century.

In 1968, John Lennon told Rolling Stone magazine: “On the end of ‘Rain’ you hear me singing it backwards. We’d done the main thing at EMI and the habit was then to take the songs home and see what you thought a little extra gimmick or what the guitar piece would be.”

He continued: “So I got home about five in the morning, stoned out of my head, I staggered up to my tape recorder and I put it on, but it came out backwards, and I was in a trance in the earphones. What is it – what is it? It’s too much, you know, and I really wanted the whole song backwards almost, and that was it. So we tagged it on the end.”

Fans, avidly searching for more insight into their favourite, global superstars in a pre-mass media and internet age, went wild for the supposed “secret” messages.

But it wasn’t until a year later that the concept, which appeared from the band’s own admission to be no more than a drug-addled in-joke, spiralled out of control, sparking the beginning of famous Beatles conspiracy theories we know today, starting with “Paul is dead”.

The story goes that in October 1969, Detroit DJ Russ Gibb was hosting his show on WKNR, when a mystery caller rang in to report that when you played “Revolution 9” from The White Album (1968) backwards you heard the words: “Turn me on dead man.”

It was “evidence”, the caller claimed, that the real McCartney had died in 1966 in a car crash on the M1 in the UK, and had been replaced by a lookalike (later suggested to be a man called Billy Shears).

As improbable as it sounds today, the story blew up. Undergraduates at US universities started writing articles in their college newspapers.

Fans scoured songs and claimed that if you listened to “Strawberry Fields Forever” backwards, from 1967’s Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, John says: “I buried Paul” (others say it sounds more like “cranberry sauce”).

They also claimed that the “walrus” from “I Am The Walrus” from 1967’s Magical Mystery Tour is a Viking (or Greek, or Scandinavian, or...) symbol of death and that 1970’s famous Abbey Road album cover is actually a symbolic funeral procession, with Lennon as the clergyman in white, Ringo Starr as the undertaker in black, George Harrison as the gravedigger in workman’s clothing and McCartney’s “lookalike” as the “corpse” of the man he was allegedly impersonating, in bare feet.

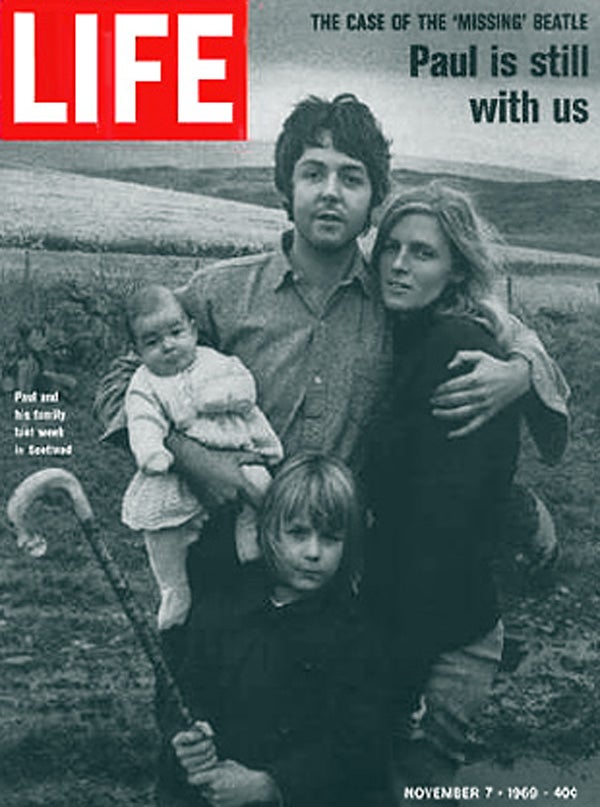

The rumours got so widespread that an interview with LIFE magazine in 1969 actually featured the headline: “Paul is still with us.”

Five years later, McCartney recalled to Rolling Stone: “Someone from the office rang me up and said, ‘Look, Paul, you’re dead.’ And I said, ‘Oh, I don’t agree with that.’”

Author Nicholas Schaffner, who published the seminal Beatles Forever in 1977, called it “a genuine folk tale of the mass communications era”.

But for whatever reason, it never really died down, becoming not just the most enduring Beatles conspiracy theory but the spark behind decades of interest in supposed “hidden” messages in their art, and a wider cultural movement.

With more and more bands using, or being accused of using, “backmasking”, by the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s some US Christian organisations had started to accuse rock ‘n’ roll musicians of using it to hide “satanic” messages to brainwash people.

In 1982, popular TV evangelist Paul Crouch accused Led Zeppelin of hiding the lyrics “Here’s to my sweet Satan” in their 1971 hit “Stairway to Heaven”.

It led to two unsuccessful attempts in the early 1980s by the US states California and Arkansas to pass legislation banning backmasking as an “invasion of privacy” that “can manipulate our behaviour without our knowledge or consent and turn us into disciples of the Antichrist”.

The Arkansas law referenced albums by The Beatles, Queen and Pink Floyd, and there were also calls for similar legislation in Texas and Canada.

By the mid to late 1980s, CDs were rolled out, making listening to records backwards much more difficult, but the rumours remained.

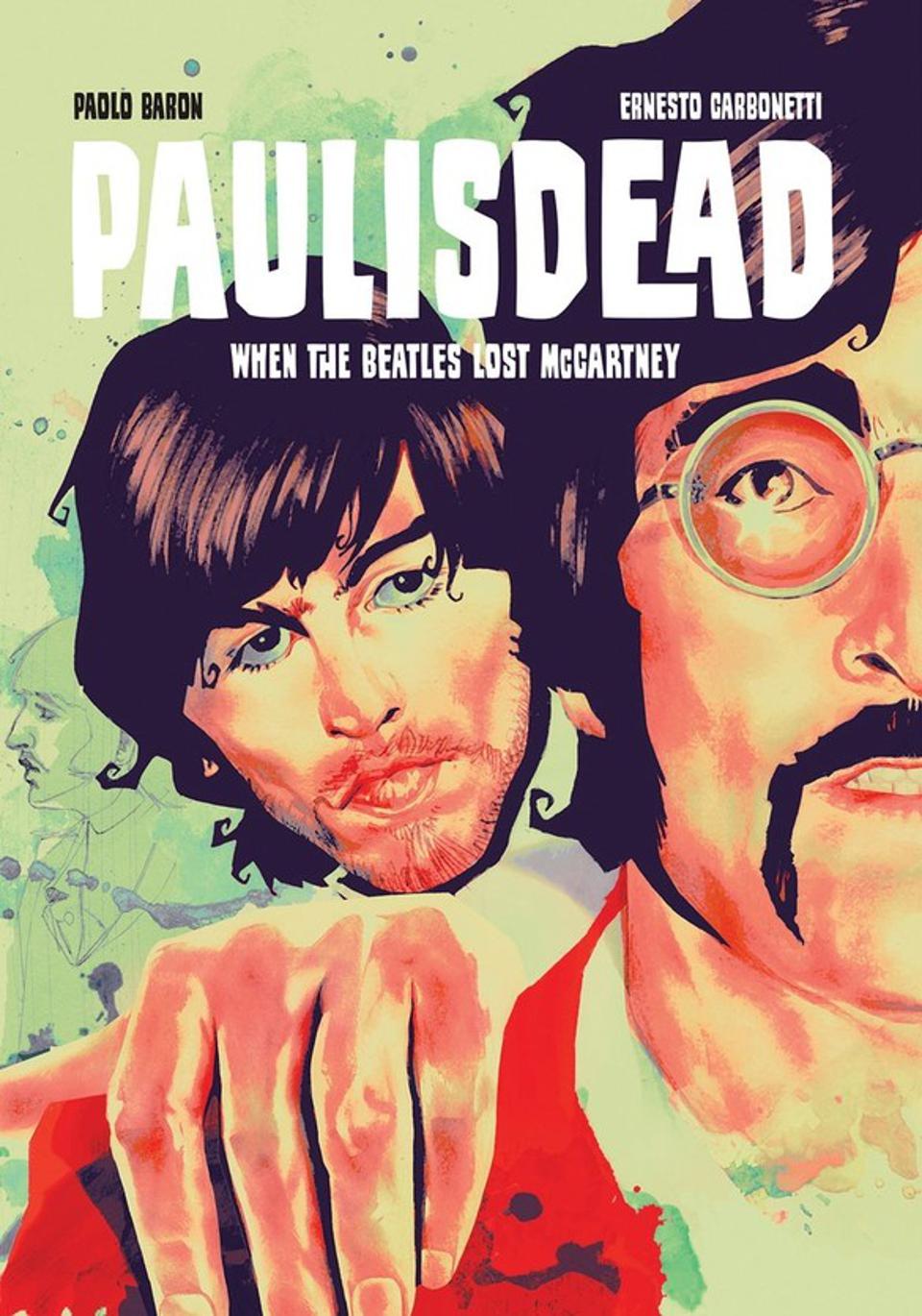

In 1993, McCartney allegedly riffed on the rumours by releasing an album called Paul is Live where he posed on the Abbey Road crossing. In 2018 “Paul is Dead” was made into a comedy film, and a comic book in 2020.

Of course, it could all be boiled down to little more than what kids did for fun before video games arrived, or a way for people to “connect” with the objects of their obsession in a pre-social media era, that all got out of control and became self-perpetuating and a part of Beatles lore.

But as well as having been the first modern example of similar conspiracy theories now affecting current music stars, like Justin Bieber (accused of sending subliminal messages) and Avril Lavigne (accused of being dead and replaced by a body double) , some psychologists have traced the whole phenomenon to an auditory form of pareidolia; when the brain makes patterns or connections that aren’t there.

Similar to people who spot shapes in clouds, or claim they see Jesus’s face burned onto a piece of toast, from Shakespeare’s Hamlet who sees a portent of doom in the sky, to crowds who claimed they saw satan (it’s always satan) in the billowing smoke after the 9/11 attacks.

In 2007, psychologist Professor Brian Wandell, now director of Stanford University Center for Cognitive and Neurobiological Imaging, told The Seattle Times that the phenomenon of hearing hidden messages in songs was partially down to the human psyche looking for structure and patterns amid chaos.

He said: “Wait long enough and certain structures will start to emerge that people will agree on because our brains are built and wired to look for things according to particular rules. So it’s not surprising that one might take 500,000 hours of famous songs and listen to them backward and occasionally hear something that everybody in the room agrees sounds like something weird – even though it wasn’t intended to be there.”

Eric Borgos, who runs the audio reversal website talkbackwards.com, similarly told The Wall Street Journal: “Mathematically, if you listen long enough, eventually you’ll find a pattern”.

Decades later, the riddle may have been solved when McCartney told The Observer in 2005 that in their 1995 “Free As a Bird” song, a reworking of a 1977 recording by the now late Lennon, they added “one of those spoof backwards recordings on the end of the single for a laugh, to give all those Beatles nuts something to do”.

Then in 2020 the now 78-year-old McCartney confirmed toThe Mirror that the secret meanings in their songs that had baffled fans for years, was, in fact, just gibberish between friends.

He said: “When you are kids you make up silly things, and what’s great about it is you and your friends all know those silly things... we were all in on the joke. So, they don’t have to mean anything!”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments