Suggs from Madness: ‘The Rolling Stones? They just keep going and ruining retirement for everyone!’

The Madness frontman might be 62, but he’s still on cackling, foul-mouthed Nutty Boy form, finds Michael Hann. He talks about growing up as ‘terrible thieves’, how the band avoided the ‘black hole’ of cruise ship offers, and the story behind the sequel to ‘Our House’ penned for their new album

When Suggs was 20, and Madness were in the flush of success that saw them reach the top 10 with 15 singles in just three years, the singer was interviewed for Smash Hits by Neil Tennant. “I said, ‘There’s no way I will be playing that f***ing “Baggy Trousers” when I’m an old man of 30.’” He laughs – cackles, rather – since that’s exactly what he will be doing next month at Madness’s annual run of Christmas shows, at the age of 62. “But the f***ing Rolling Stones just keep f***ing going and ruining it for everyone. You’re supposed to be f***ing dead now!”

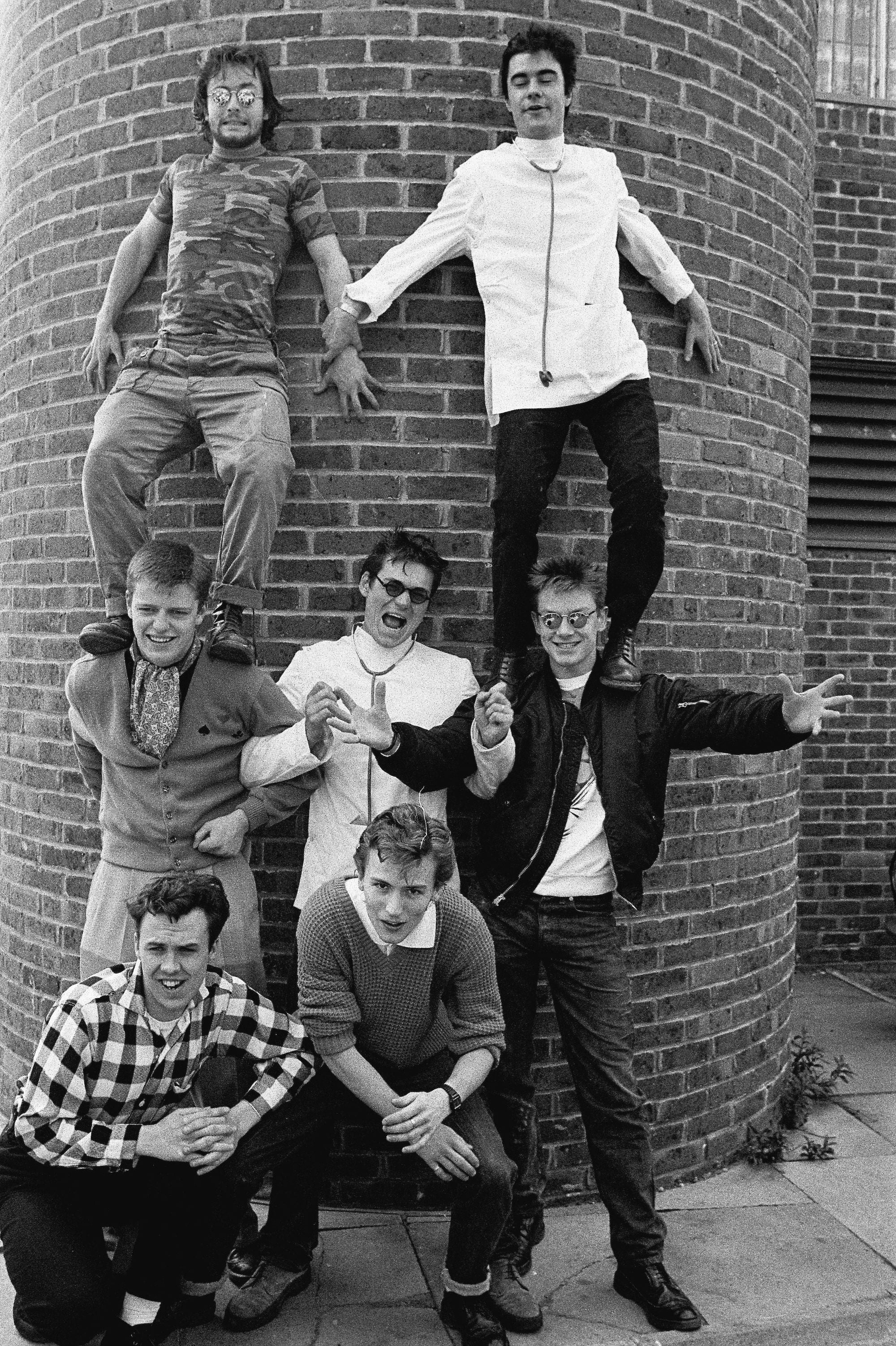

Back then, Madness were the Nutty Boys: street-smart (and street-tough) kids from Camden Town and Kentish Town, whose songs reflected the turmoil of teenage life with wit and empathy and joy. They were the band who, as one of their songs put it, kept going “One Step Beyond” – in their videos, in their ability to create chaos that they just about harnessed. These days they are rather more venerable. Suggs is in his seventh decade, though his ability to insert expletives into any sentence is a testament to that past.

It’s also an indication of how combustible Madness can be. They can disagree about anything, Suggs says. At the moment, it’s what they’ll be playing at those Christmas shows. “There’s huge arguments about how many songs we play off this new album. But who do you think’s coming? Do you think there are going to be any office parties there? What do you reckon? Do you want to hear our new album, with your party hats on? I don’t think so. So do five or six new songs, for your own mental health. But then they’ve got to be given the big guns, out of the old purple velvet bag of joy.”

The new album is Theatre of the Absurd Presents C’est la Vie, the fourth record in a late-career renaissance that began with a concept album about London, The Liberty of Norton Folgate (2009), described recently in the Telegraph as “the equal of any LP released by an English band this century”. The new one is presented, almost music-hall style, in a series of acts, introduced by spoken word sections, for what appears to be no good reason. “Between you and me, it’s an absolute nonsense affectation that we came up with at the last minute,” Suggs says. “You say it’s a concept album, and it becomes a concept album. And the concept is whatever you want it to be. When we did Norton Folgate, the concept was our history and connection with London, and we were halfway through and Chris [Foreman], our guitarist, said, ‘What have all our other songs been about then?’”

One of the most striking songs on the new record is “In My Street”, written by Suggs, which comes over as a sequel to the beloved 1982 single “Our House”. It was prompted by him moving away from the little patch of north London in which he had lived for most of his life – and where the band met and which they mythologised – to Leyton in east London, to be closer to his kids and grandkids, who couldn’t afford to stay in the area they’d grown up in.

“When I was moving out, I was having memories of that street. It’s slightly sentimental. But it’s funny – I remember talking on stage about ‘my band’ and a couple of them afterwards went, ‘No, it’s our band.’ And it’s ‘Our House’, whereas I wrote ‘In My Street’. I don’t know if that says something about me.”

It’s a little reminiscent, too, of Before We Was We: Madness on Madness, Tom Doyle’s oral history of the band – though that book is unusual in that its interest lies in the social history of the inner north London suburbs in the 1960s and 1970s rather than the music (it ends as Madness reach the charts). It’s one of the best books about music because it concentrates on what made the band what they were. It’s a book about Madness’s great subject: London and living there.

“In Camden Town, as a young man, the biggest problem was that I didn’t see a girl – I didn’t know there was an opposite sex till 1982, because all you had was blokes in pubs. But then the music scene really kicked off with punk. You had all these fantastic pubs, probably about 12 of them. You could go out every night and watch music for nothing. Another thing I recall is never ever thinking about money. You just went out and walked about and kipped on someone’s sofa.”

Well, perhaps he never thought about money because, as the book makes plain, the young Madness never paid for anything. Suggs sniggers. “There was that. We were a terrible bunch of thieves. Mike [Barson, keyboards] says in that book, ‘I can’t remember paying for records, but I must have stolen a lot, because I had 400 of them.’” He sighs at the memory. “That poor chap in that shop Rock On – he used to chase us down the road.” That leads on to a series of reminiscences about the shops that are still there – the Ben Nevis Outdoor Clothing Company on Royal College Street, where I stock up on waterproofs before festival season, and from which Madness used to nick that essential element of Seventies skinhead garb, Harrington jackets.

I remember we were in America and the crowd all sat down and booed

Then there’s the British Boot Company, just up from Camden Town Tube, which Suggs recalls, “used to be run by Alan Holt. And he was a character. He used to have a Ford Zephyr and, in the days when you could park, he used to park it out front and it was so big he actually had a drum kit in the boot. He was an old swing drummer, and it was just in case he got a gig. He said to me, ‘Have you seen that Elvis Costello recently?’ I said, ‘Look, Alan, I gotta tell you, whatever you might imagine, there isn’t some world where pop stars just all congregate together. We barely see each other because we’re on the road or doing what we’re doing.’ He said, ‘Well tell him he owes me a tenner for his brothel creepers.’”

Madness’s first burst of fame lasted just five years, from 1979 until the departure of Barson. The group soldiered on for one more album, then four of them made another as The Madness. The joy had gone by then: the group resented not being taken as seriously as others whom history remembers less fondly, they were fed up of having to be caricatures instead of people. “We were going round Europe doing TV shows and they’re going, ‘Come on! Be wacky! Be nutty!’ And you just start getting a little bit exhausted. Having said that, every time we would do it. ‘Would you like to dress up as legionnaires?’ ‘No, f*** off, don’t take the p***.’ Ten minutes later, we’re all dressed up as legionnaires running around in circles.”

Half the time, Suggs accepts, they did the damage themselves: he looks back with particular horror on performing “Night Boat to Cairo” on Top of the Pops in 1980, in pith helmet and khakis. “That was a low point. I knew as I was putting these khaki shorts on that it was going wrong. But we had these very serious costumiers called Berman and Nathan’s in Camden Town. They were doing films and you’d go in there and it would be all the gear from Lawrence of Arabia, all the gear from Oliver!. They liked us and they trusted us enough to give us authentic coppers’ uniforms or parking wardens or whatever. We’d just run out of things to dress up as: we dressed up as mushrooms, flowers, f***ing everything, but it was great fun. Young people jumping about in fancy dress. Fantastic.”

Eventually, though, Suggs says, the fun lessened, the stress worsened and “it got more and more dark to the point that we ground ourselves into a hole. I remember we were in America and the crowd all sat down and booed. I don’t know if you’d call it self-indulgent, but we just didn’t feel like being told to be funny.”

After the group called it a day, there was the inevitable period of drift. Suggs saw a psychotherapist who told him he was scared of the blankness but he should instead see the opportunity ahead of him. He had kids, he managed the band The Farm, and then in 1992, Madness reunited off the back of the smash-hit Divine Madness compilation and played two nights in Finsbury Park. Suggs had initially been reluctant to reunite, and he certainly didn’t want to tour, but the old ties reasserted themselves, and Madness again became a band.

We didn’t want to go down the cruise ship spiral

But being Madness was still a role, and though they made new albums, they felt they had become trapped again in the run-up to The Liberty of Norton Folgate. “We were getting to the point where we were getting offered all those big Eighties tours and cruises and it weren’t gonna be too bad financially, but we realised, ‘F*** this, we’ve got to try and get out of this’. So we worked really hard on that album, and it was the first time that we ever got any intellectually good reviews. It felt like the moment in Star Trek, where you’ve got to get out of the black hole and get to warp factor 12. ‘I dinnae think she can take any more, Captain!’ And then from then on, we’d be making records for ourselves and the hardcore fans. But ultimately for ourselves, to ensure we don’t go down the cruise ship spiral.”

Even as Madness are nowadays lauded alongside Ian Dury and Ray Davies as the great chroniclers of London, it’s jarring to realise just what a “local” band they really were. You could easily walk the landmarks of Madness’s London in a day, starting at King’s Cross and working north for no more than a couple of miles. And Suggs sounds discombobulated talking about having moved from Tufnell Park to Leyton – 6.8 miles by road – as if it’s a completely different world there. But it’s in the details and the differences that he learnt to find a voice that spoke to everyone.

“I always remember Ian Hunter [of Mott the Hoople] saying, when they asked him, ‘Why did you write All the Way to Memphis? And he said, ‘I’m hardly going to write All the Way to Walthamstow.’ But Ian Dury did. He found out that you can make universal stories out of your own very small detail. Like ‘Have a Cuppa Tea’ by The Kinks. If you express it as realistically as you can, everything becomes universal. Everyone’s had a girlfriend who gets annoyed when you want to go to football, or whatever.”

The songs on which Madness expressed those sentiments – “My Girl”, “Embarrassment”, “Baggy Trousers”, “Our House” and the like – are now part of the national consciousness. They’re more than pop songs, they’re cultural shorthand for Britain. “And it’s still great fun,” Suggs says. “People talk about learning a craft, and I hated that when I was a kid – I hated to think it was a job or something like that – but ultimately it is. And then you do your job, and if you do it well you get the rewards of people digging what you do. And that really is very enjoyable.”

‘Theatre of the Absurd Presents C’est La Vie’ is out now via BMG

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments