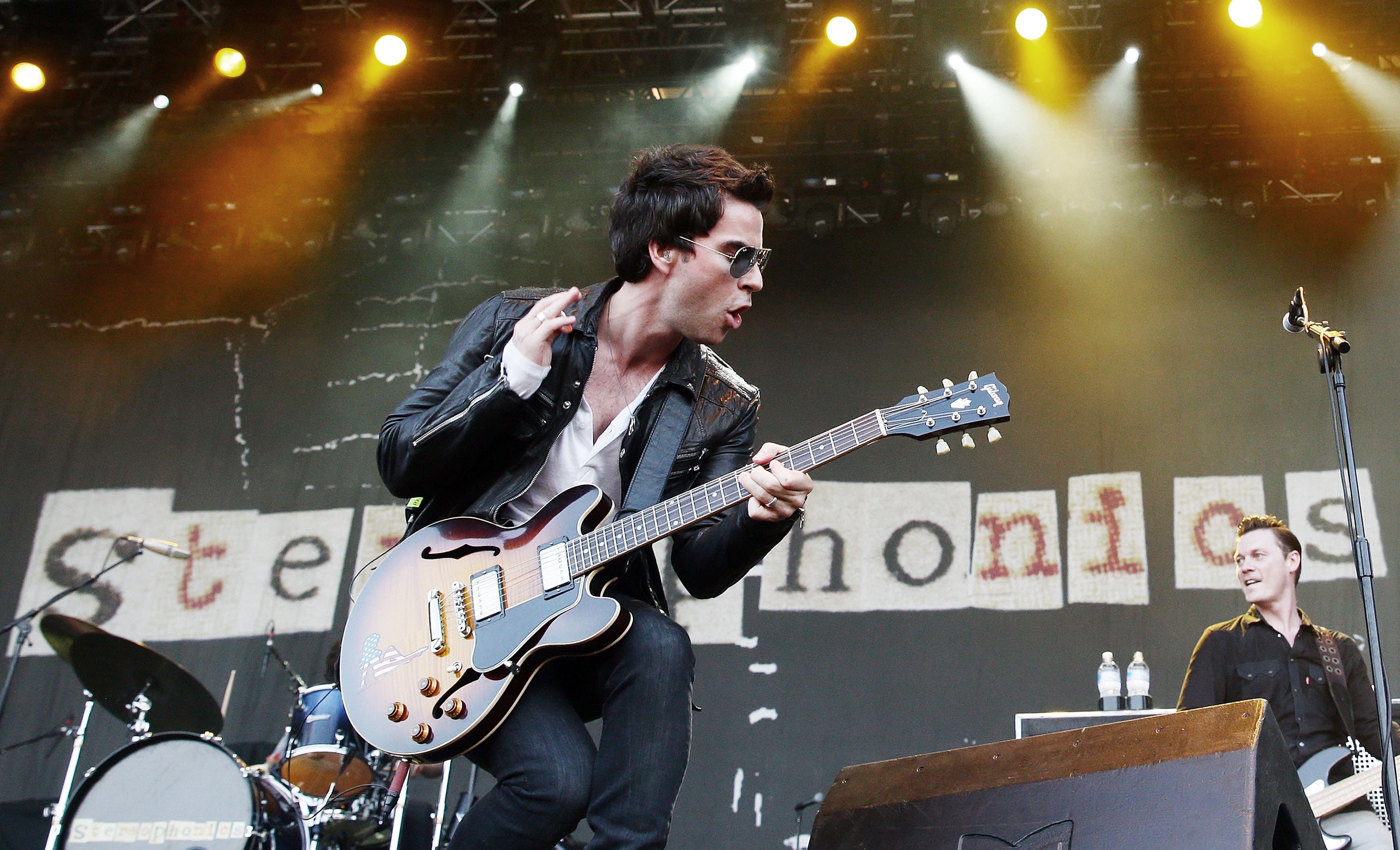

Stereophonics’ Kelly Jones: ‘I stand by what we did. We followed the guidelines at the time’

As the band release their 12th album, ‘Oochya!’, frontman Jones talks to Kevin E G Perry about their controversial pandemic show in Cardiff, his late drummer Stuart Cable, and why he’s speaking out about his trans son

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On Thursday 12 March 2020, Kelly Jones, his Stereophonics bandmates and their crew gathered in front of a television screen to watch the prime minister address the nation. “That was the first day Boris Johnson went on telly with those scientist guys, and they said: ‘Nothing’s closing down. Everything continues as it is,’” recalls Jones from his studio in London. The announcement was met with relief, as it meant the band were clear to go ahead with a pair of headline shows at Cardiff’s Motorpoint Arena that weekend.

It was only after the gigs were done that Jones, who doesn’t use social media, realised he’d inadvertently found himself at the centre of a national controversy. “I got back to my house in Wales and someone said: ‘Piers Morgan’s been having a right pop at you, hasn’t he?’” he remembers. “I didn’t know what they meant, because I knew Lewis Capaldi was doing shows, and the West End was still running.”

That same weekend, Premier League fixtures were suspended, as was Wales’s Six Nations rugby match against Scotland, but Jones says even with hindsight he has no regrets about pressing on with his band’s performances. “I stand by what we did,” he says, matter-of-factly. “We followed the advice. I had my own family there, including my parents, my pregnant wife and my five-year-old. If we upset people, we upset people, but we followed the guidelines at the time.”

The furore overshadowed the end of a tour that had otherwise been triumphant for Jones. In late 2018, during a routine health check-up, his doctor spotted a vocal polyp that required surgery. Jones feared he might never sing again. Fortunately, the operation in January 2019 went smoothly and within months he was back behind a microphone.

“I went pretty hard on it,” says Jones, now 47. “I’ve got a brilliant coach called Joshua Alamu and he had me blowing f***ing straws in bottles of water. It was bizarre, man, but I think I’m singing better now than I ever have. It ended up being a good thing to do at this point in my life, getting older. A bit like an athlete, you learn how the muscles work and then you can use them better.”

But the pandemic did something that even vocal surgery couldn’t: it forced Jones to slow down. He says he “didn’t do much” during the first year of lockdown, taking the opportunity to spend time with his family. His wife, Jakki, gave birth to his fourth child early in lockdown, a “f***ing weird” experience as “you’re allowed in for labour, and then you’re told to leave four hours after”, adds Jones.

He also helped homeschool his older children, including his son Colby, who had been dealing with transitioning while attending an all-girls school. “He’s in a great place now, at the BRIT School doing digital design,” says Jones. “When he was in the all-girls school that was a lot more tricky, because he didn’t feel like a girl any more. He did f***ing brilliant at GCSEs, all As and A*s after all that time out, and me and my wife are supporting him as much as we can.”

Jones first spoke publicly about his son’s transition in 2020, and says he hoped that by making their story public it would help reassure fellow parents in similar situations. “I was trying to think: ‘Who do I know who’s going through this?’ Well, nobody. I don’t know anybody who’s going through this,” he says. “If other families are going through it the same way I was, I just wanted to talk about it a bit.”

The enforced slowdown also gave Jones time to reflect on his journey in the 25 years since the release of the Welsh rockers’ debut, Word Gets Around.“Right Place Right Time”, one of the stand-out tracks on new album Oochya!, their 13th, looks back even further. It’s a frank, introspective song that embraces the band’s past while signalling Jones’s desire to avoid becoming merely a nostalgia act. In part, it is addressed to his childhood friend and original Stereophonics drummer Stuart Cable, who choked to death after a three-day drinking session in 2010. “You got drums / I got a guitar,” sings Jones. “When we made up a band / Who knew we’d go far?”

Jones and Cable grew up in the small Welsh town of Aberdare just a few doors down from each other: Jones at number 54, Cable at 62. He vividly remembers watching his friend unpack his first drum kit, a “Ferrari red Pearl drum kit from the music shop in Aberdare town centre. I’d never seen anything like it. He was a big Rush fan, so he was loving it.” They started out playing covers together: AC/DC, Beastie Boys, “anything that was easy with an overdrive pedal”.

They played their first gig at the local Working Men’s Club when Jones was just 12, opening with Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Bad Moon Rising” and Van Halen’s “Jump” before slipping in a song they’d written themselves. “We rehearsed every Thursday and every Sunday for 10 years,” remembers Jones. “F*** knows why, but something was driving us to continue.”

Jones’s father, Arwyn, had been a professional musician himself, recording under the name Arwyn Davidson, as his label, Polydor, felt there were already too many Joneses in the music industry to keep up with. He had some success, supporting Roy Orbison and releasing a cover of Graham Nash’s “Simple Man”, which Jones remembers hearing on his local pub’s jukebox. But he never reached the heights his son has achieved: headlining festivals, winning a Brit award in 1998, and selling more than 10 million albums worldwide.

Jones remembers him offering cautionary tales about the music business. “I think he was trying to put me off a bit,” he says. “He wasn’t a massive talker about it, but bit by bit you’d have these little seeds dropped: ‘Oh, I recorded in Air Studios. Dudley Moore was the piano player and George Martin was the producer.’ Bit by bit you’d piece things together, but when me and Stuart were getting ambitious, my old man would be saying: ‘Be careful, you’re going to get burned.’”

There were so many bands in the Nineties, and unless they stuck at it and wrote some decent songs they all died off

Stereophonics signed their first record deal in May 1996, a decade after that first Working Men’s Club gig, and released their debut album the following August. Looking back now at the wave of bands who got their break in the wake of Britpop, Jones notes how few of their peers are still putting out music. “We saw so many fall away,” he says. “There were so many bands in the Nineties, and unless they stuck at it and wrote some decent songs they all died off.”

Jones’s own ability to fashion a decent tune was evident right from the release of the band’s first single, “Local Boy in the Photograph”. Written, like many of his early songs, while working on a market stall, it tells the story of Paul David Boggis, a young man who Jones knew who was killed by a train travelling between Cwmbach and Aberdare.

“He was a great kid, a good-looking kid,” remembers Jones. “I was working in the market and he came in and had a chat, said he was going someplace. Then I remember being at my mate’s house and hearing what happened. I was thinking: ‘F***, I only just spoke to him.’ His family came up to me in about 1997 saying they took it as a celebration, which was a relief because I didn’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings by writing about him. Then it becomes the first single, and all these people are jumping up and down in a field f***ing singing it back to you. It’s had quite a journey, that track.”

The song showcased Jones’s knack for writing concise, impressionistic lyrics about everyday life – a skill he developed at art school, before the band took off, by writing screenplays for short films. Songs like “She Takes Her Clothes Off”, from chart-topping second album Performance and Cocktails, were based on dialogue he’d written for scripts, while hit single “The Bartender and the Thief” was inspired by a VHS copy of Eighties crime drama The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover.

Jones hasn’t given up on his dream of having a screenplay produced, coming closest in 2012 with Graffiti on the Train, a title and story he also used for the eighth Stereophonics album. The film version was set to be made with 1917’s George MacKay and Dunkirk’s Aneurin Barnard before financing fell through. “Now those two are in everything, so at least I picked some good people!” says Jones with a wry laugh. “I had a period of time where I was very focused on scriptwriting, but it’s a very collaborative sport so you can’t do it in the middle of all this s***.”

In 1999, the same year Performance and Cocktails made the band a household name, Stereophonics teamed up with Welsh music icon Tom Jones to cover Randy Newman’s “Mama Told Me Not to Come”. It gave the band another hit, and a perfect excuse to go and see the man himself complete one of his famous Las Vegas residencies.

“He had a 15-night stand in Vegas, and we got there on the 14th night,” remembers Jones. “We watched his show and then he took us out all night to this place called Studio 54, but in Vegas. Then we went back to his room and he told us stories until it came light. The next day, he walked on stage and he had 11 glasses of water on a table. He put the spotlight on us in the booth and said to the audience: ‘If you’re wondering why these 11 glasses of water are here, it’s because these b******s kept me up until seven in the morning!’ What a f***ing legend.”

As the Stereophonics’ star rose, Jones would rub shoulders with many more of his heroes. He became friends with Rolling Stones guitarist Ronnie Wood through a shared producer, and recalls surreal parties at Wood’s home in Kingston Hill. “It’d be f***ing nuts up there,” he says with a grin. “You’d be playing snooker with Ronnie O’Sullivan and Ronnie Wood would be the referee.”

When they supported the Stones in Paris in 2003, Cable caused a minor incident by digging into Keith Richards’s shepherd’s pie before the guitarist had broken the crust – strictly against Stones tour protocol. Jones remembers Richards taking great delight in explaining to his young children where Wales is. “He drew a map of Great Britain and put a red line around Wales, saying his grandparents were Welsh,” he says, adopting an appropriately piratical slur as he recalls Richards telling his daughters: “... and that’s where the dragons live!”

The following year, Stereophonics joined David Bowie for what would prove to be his final tour across America. Once again there was a surfeit of surreal moments, like Bowie heckling from the sidelines as they played five-a-side football against his crew and then mockingly lowering a trophy on a string over their heads during the gig after they lost. Jones remembers Bowie for his dry sense of humour and approachability. “We’d watch him soundcheck and he’d go: ‘What do you think lads, should I do that one tonight?’, says Jones with a raised eyebrow. “I was just like: ‘F***ing hell mate, you’re asking me?’”

It was while on tour with Bowie, passing through the town of Vermillion in South Dakota, that Jones wrote “Dakota”, which became his band’s first No 1 single in 2005. By that point, Stereophonics had been selling out arenas and headlining festivals for years, but Jones says he struggled to come to terms with their success. Even when they’d headlined Glastonbury in 2002, he’d found it hard to wrap his head around the fact that anyone actually liked his band.

“I think it’s a working-class, small-town thing,” he says thoughtfully. “You don’t really get pats on the back and people saying: ‘Go for it son.’ People don’t mean to do it, but there’s an underlying negativity in those towns. When you start achieving stuff, you’re on the back foot. You can be in front of 90,000 people thinking: ‘Well, what are they all here for then?’ It’s ridiculous really because at shows your name is on the f***ing ticket! You’re a kid from a dead end street one minute and the next you’re on the front of all the magazines in the f***ing country. It took us by surprise.”

It was only after the success of “Dakota” and fifth album Language. Sex. Violence. Other? that Jones felt some sort of acceptance of what he and his bandmates had achieved. “I started to go: ‘Well, this is five albums in now! People are actually into what we do.’ It sounds stupid when I say it out loud, but that’s how it felt.”

These days, Jones seems to have overcome his crisis of confidence. He’s helped, no doubt, by the statistics: Of the 11 albums Stereophonics have released before this year, no fewer than seven have gone to No 1. As we we sign off, I ask Jones if he’ll be disappointed if Oochya!, a fast-driving record he calls “uplifting and positive”, fails to similarly top the charts. The question causes him to break out into a toothy laugh. “Yeah,” he says, clearly no longer troubled by false modesty. “Yeah, I will be!”

‘Oochya!’ will be released on 4 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments