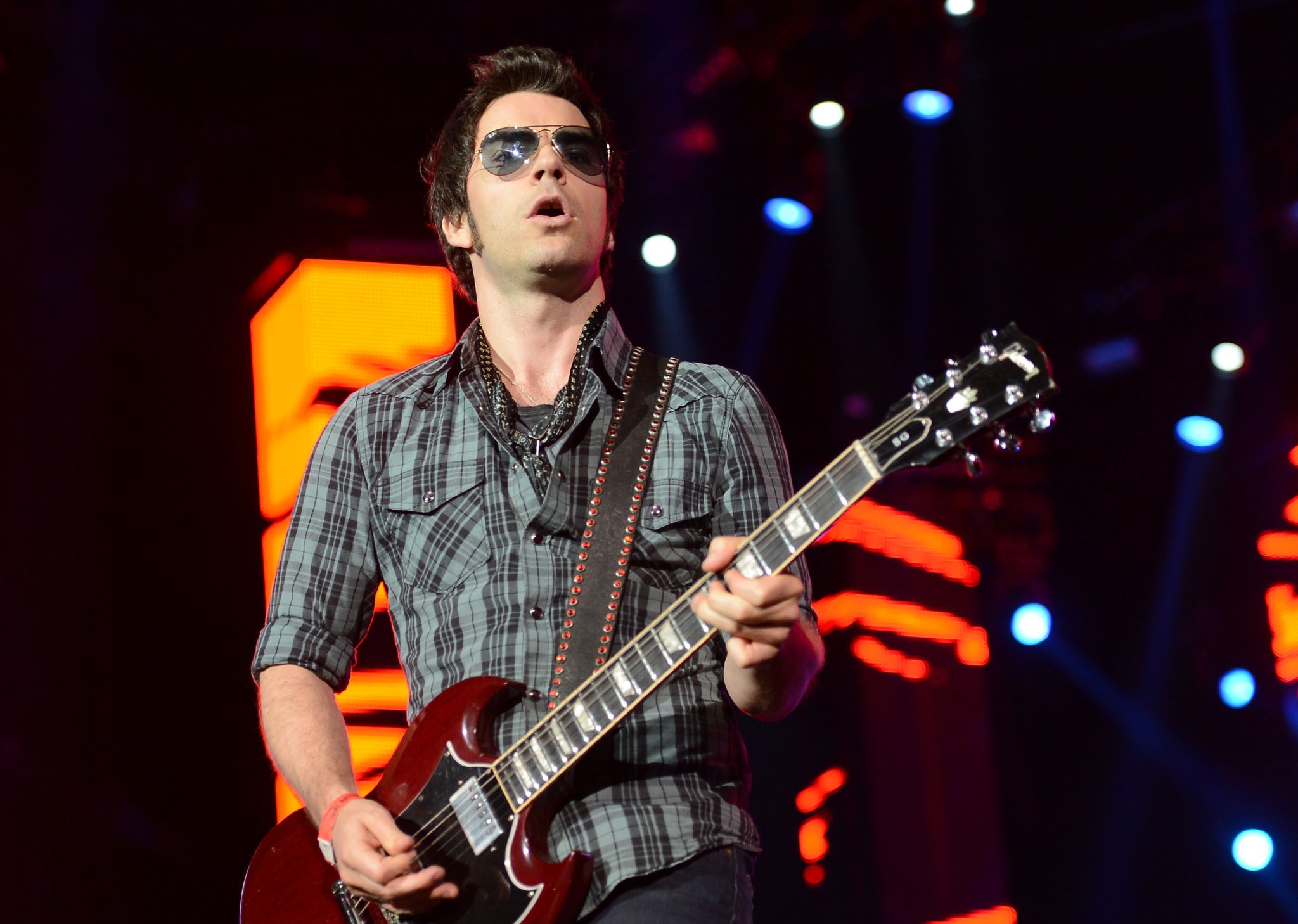

Stereophics interview: Kelly Jones on the Britpop heyday: 'People are way more diplomatic now, compared to what we were then'

Kelly Jones had a low-key upbringing. Coming from a small village in Wales, he grew up with his bandmates and spent his early years doing amateur boxing, selling fruit and veg at the local market, and trailing round with his dad, a musician, to local pubs. It didn’t really prepare him for a life as the frontman of one of the most successful rock bands to come out of the Nineties, and it has taken a while for the 41-year-old to adjust.

“I was the youngest of two older brothers and my dad was singing in working men’s clubs. I was sent into pubs in my pyjamas, but people started to accept that, because I was Oscar’s little boy and he had a record on the jukebox when I was a kid. So I guess I was accepted into that circle of people who would talk very openly. It was a small town, lots of gossip, lots of rumours, some of them very tragic, some of them very funny, very sarcastic.”

Those stories and adolescent experiences were woven into the band’s first record, Word Gets Around, released in 1997, which led to them receiving the Best Newcomer award in 1998 at the Brits. They were still relatively unknown then and everyone expected All Saints to win but Jones strode on stage and infamously announced: “It’s about time for some fucking recognition, thanks.” That quote has gone down in the annals of rock history for its ballsy, laddish arrogance, which in many ways epitomised the attitude of Britpop bands of the time.

“The things we all said in the Nineties, they change a little bit don’t they?” he says, a glint in his eye. “I’d been in bands since I was 12 and by the time I was signed I was 23, I felt like I’d been doing it a long time but obviously in the public’s eye it had been, like, six months,” laughs Jones when we meet in a hotel in Kensington, west London. He still has the strong Welsh accent and dry humour from his early days.

“It was a period of time when everybody was trying to stir something up week after week in the press and if it was jumped on and you said the wrong thing then it lasted too long. So you can just imagine, we came from a small town that was one road in, one road out, and that was it. And when we broke out of it, we did the Britpop thing, us and the Manics and it was all just bollocks, really. I think we did have opinions and that’s what it’s about. It’s kind of the equivalent of what Twitter is now. People are way more diplomatic now, compared to what we were then.”

When Jones left college he wasn’t sure exactly what he wanted to do for a living and began a course for the unemployed in scriptwriting. At the end of the course he pitched his idea to Carl Francis, who was the head of BBC Wales.

“He offered me to write an 11-page treatment, paid, and then weirdly Richard Branson offered me a record deal. So it was a good month but it was like, which way are you going to go?”

Jones took the record deal but over the last few years he has been exploring the film route too. He now has a hand in directing all the band’s videos and has a screenplay in the works which ties the upcoming album, Keep the Village Alive, and the last album, Graffiti on the Train, with a loose narrative about two boys leaving their village for pastures new. It’s based on episodes from his youth as well as more recent events, like the death of Stuart Cable, the band’s former drummer and Jones’ childhood friend. After Cable’s death, after a bout of heavy drinking, in the summer of 2010, Jones went through the most creative period of his life since the first album.

“I never understood that when people said after the first album I’d have nothing to say. I thought, if people don’t have anything to say they can’t be doing much,” he says, describing how the themes of the film gradually morphed from being about two young boys into a reflection of his own youth and a meditation on his friend’s death.

“It’s a cross between Stand by Me and Quadrophenia. I guess [the process] dug down inside me and it brought up a lot of stuff. I think some of the emotions are about things that happened when I was younger, possibly because Stuart died in the summer of 2010 as well.”

The video for single “C’est La Vie”, with its playful, youthful exuberance, is about two young men fighting over the same girl. It probably derives from when Jones broke up with his girlfriend of 12 years in 2002, only to discover his friend and the band’s photographer, Julian Castaldi, had started dating her. Jones smashed in his front door and vandalised his two cars with a piece of scaffolding, later saying it was “out of character”.

These days, if Jones gets a bit tipsy, he tends to be the victim of his own folly. A few weeks previously, he decided to test out a BMX bike belonging to his daughter (he has two children, Bootsy and Misty, with his former girlfriend, interior designer Rebecca Walters and is now married to MTV journalist Jakki Healy) and ended up smacking his head on the floor. “It was a good night, fucking headache by the end though,” he deadpans.

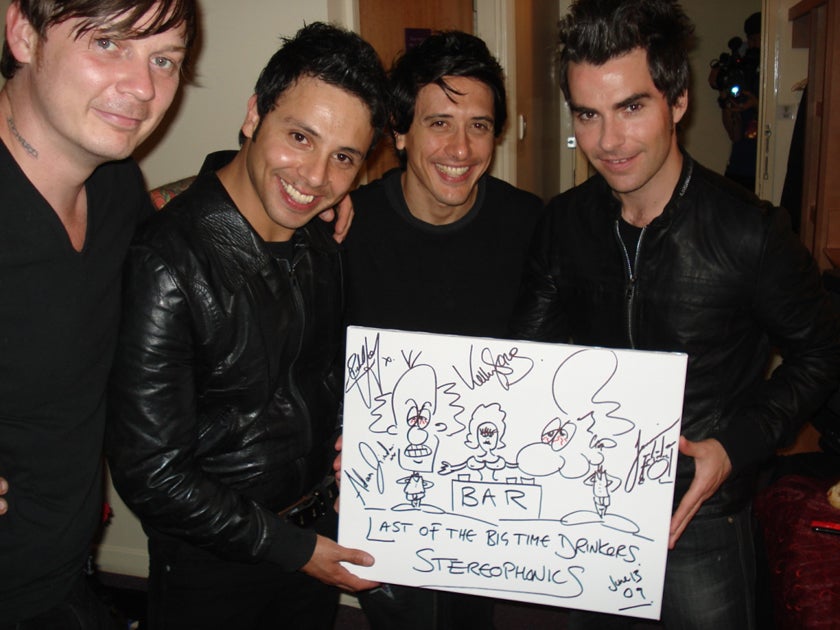

Jamie Morrison, the drummer who joined in 2012, stopped drinking about 14 months ago. “He’s a lot better for it,” Jones says with a smile. “He’s not an alcoholic, trust me, but we’re allowed to go into countries now we weren’t allowed in before.” Morrison, who came to watch the band 25 times as a fan, has quickly slotted in with the tight-knit group.

While the band and its sound continues to grow and evolve, Jones has also been considering bringing someone in to write with him, which he has never done before, and Grammy Award-winning producer Frazer T Smith, who worked on Adele’s “Set Fire to the Rain”, and James Morrison’s “Broken Strings”, has suggested they work together.

Although he still loves performing and music, Jones says he “never felt comfortable doing the other bits”. When I ask if he’d like to see his two daughters take the same path as him, he hesitates. “I don’t think you really take on board when you’re younger how much it’s going to take over you the older you get. As much as you think you can put it down whenever you want, you can’t, because you’ve made it part of your system. So that whenever things happen to you, you express them out. I’m glad that I can do that because a lot of people where I come from, that are my age, they couldn’t do that. Some of them wouldn’t have the balls to do it.

“I mean, at the end of the day it’s a bloke writing poetry to music... but I think people now, they look at the television and they think, ‘I could do that’, because they want what comes with it, but we didn’t want to be famous really, that’s the truth.” Then he corrects himself, “Well, Stuart did. All he wanted to do was be famous, and have a swimming pool and a fast car, but to me that was the last thing on my mind. I didn’t even know why I wanted it; I just knew I loved this thing.”

‘Keep the Village Alive’ is out on 11 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks