The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The need for speed: From Springsteen to SZA, where did the rapid-fire remix trend come from?

Between mainstream artists and emerging indie acts, sped-up remixes of existing songs are fetching millions of streams every month. Nadine Smith brings us up to speed on the DIY history behind the industry’s latest trend – and where it can go from here

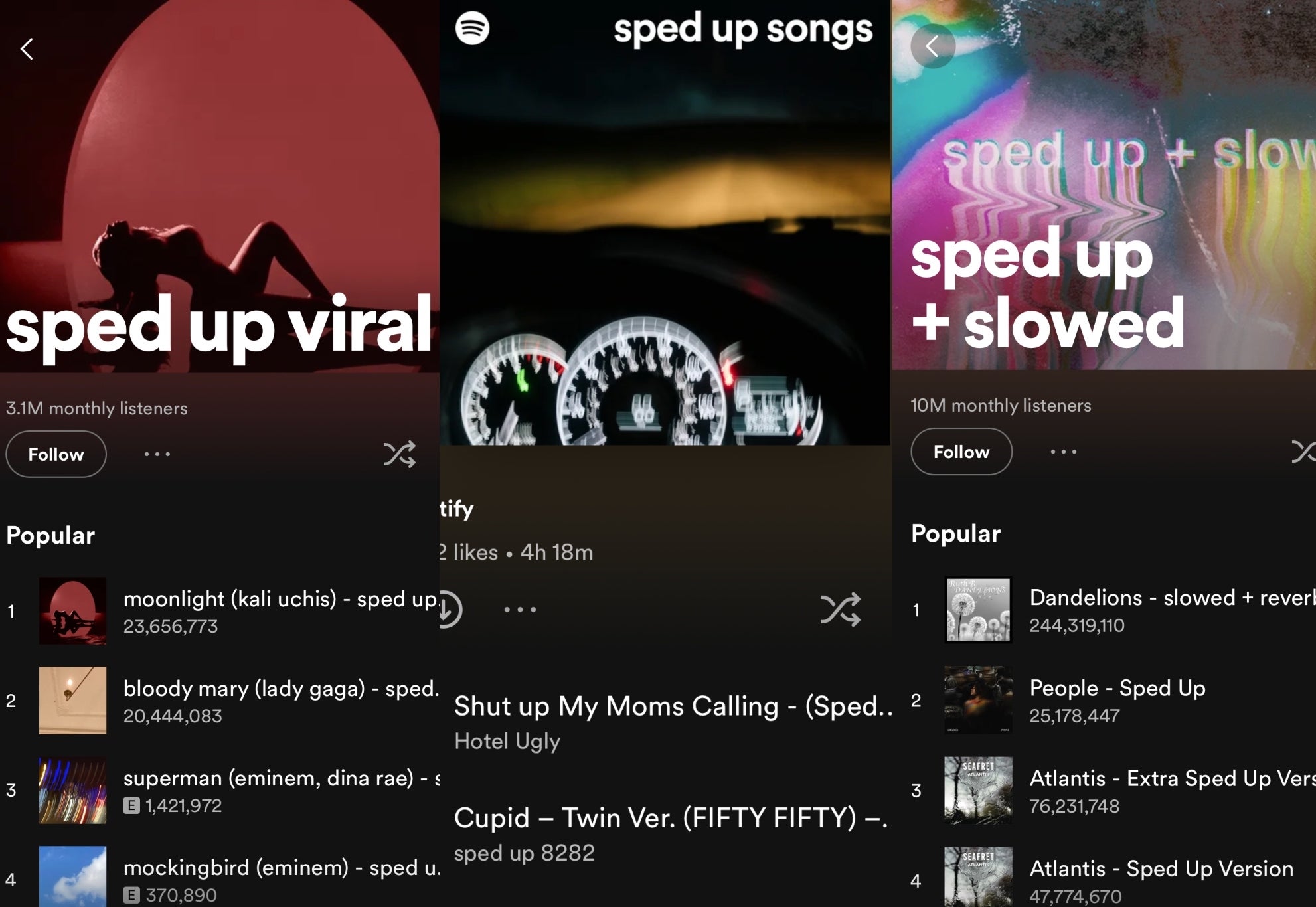

To be alive today can feel like a perpetual state of acceleration, overloaded as we are with information and stimulus at a whirlwind rate. It makes sense, then, that over the past few years, pop music has quite literally been speeding up. If you’ve been on TikTok or hit shuffle on a ready-made Spotify playlist in the past year, you’re probably familiar with the sped-up remix: from mainstream pop stars like Miguel and SZA to emerging indie acts, artists have racked up major streaming numbers with high-pitched and extra-fast remixes of their existing work.

The result is exhilarating. Take “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” as an example. The Tears for Fears hit from 1985 is a classic pop/rock karaoke staple, but turn up the tempo and it becomes a thumping club beat. Meanwhile, a remix of Jason Derulo’s “Whatcha Say”, which samples Imogen Heap’s folktronica ballad “Hide and Seek”, has both artists sounding like they guzzled a litre of helium. It’s not just the voices that change; the extra-fast “A Thousand Miles” turns Vanessa Carlton’s iconic opening piano line into the kind of hyper-charged loop you might hear on an old-school rave track.

For almost as long as there’s been recorded music to play, people have been playing it at the wrong speed. It’s an experience we all know, whether that’s spinning an LP at 45 RPM or accidentally hitting fast-forward on a podcast. From chipmunk soul to the literal Chipmunks, there have been countless creative and commercial uses of pitch-shifting. It’s a technique that became even more prevalent with the rise of digital samplers that enable the human voice to be manipulated beyond recognition.

Sped-up samples and high-pitched flips have long been elemental to styles of dance music like jungle and happy hardcore, a style of high-BPM rave music that’s full of bright colours and cartoonish voices. Historically, though, these forms of remixing were usually much more involved and labour-intensive than merely changing the tempo; it’s only in the past decade or so that speed itself has become an aesthetic virtue and a commercial selling point.

Right now, the #spedupsounds tag on TikTok has over 20 billion views and rising. Sure, there’s an obvious novel appeal to hearing an altered version of a song you already know, but increasingly these pedal-to-the-metal remixes are a way for unfamiliar voices to break through. Look at Cafuné, the indie-pop duo who were signed to Elektra Records after a sped-up remix of their 2019 single “Tek It” went viral on TikTok two years after the song was released. You can even hear the sonic trend’s influence outside of literal remixes, whether it’s the supercharged hyper-pop of artists like 100 Gecs and Charli XCX, or the pitch-shifted falsetto flows of rappers like 454 and Eem Triplin.

Like most trends, the music business did not invent the sped-up remix. Before it, there was the nightcore remix, an underground genre that proliferated on YouTube and SoundCloud around the 2010s. The nightcore formula was simple: take an existing song, speed it up, and put it over images of animé. A New York Times profile traced the origin of the term “nightcore” to two Norwegian musicians, Thomas S Nilsen and Steffen Ojala Soderholm, who recorded high-BPM tracks in the late 2000s under the nocturnal moniker.

In the early 2010s, nightcore was just one of a legion of electronic micro-genres that sprang up on SoundCloud and YouTube. Others had names like “vaporwave”, “hypnagogic pop”, and “seapunk”, which described an aesthetic vibe more than the sound itself. Despite their individual stylistic differences, what united all of these adjacent scenes is that they were primarily driven by unlicensed samples: while nightcore was speeding up anything and everything, vaporwave producers were slowing down R&B and throwback pop to make uncannily haunting chopped-and-screwed compositions, like, say the slowed-down remix of Diana Ross by producer Macintosh Plus.

Before collaborating with The Weeknd and scoring Adam Sandler’s hit 2019 film Uncut Gems as Oneohtrix Point Never, Daniel Lopatin produced Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1, a woozy compilation of distorted remixes by everyone from JoJo to Fleetwood Mac to 2Pac.

“I don’t know that there were ever really nightcore artists per se,” says music critic Sam Goldner, who specialises in sample-heavy electronic scenes like vaporwave and hyperpop. “Even compared to something like vaporwave, which had more names that emerged from it, nightcore had an organic fan-made vibe, mostly random mixes and YouTube videos.”

It’s the cobbled-together nature of nightcore that’s notably missing from its corporate offspring, which fits in effortlessly with pre-fabricated playlists. “That makes it strange to see on this major mainstream level. I was in my office today and had some Spotify radio playing, and it played the SZA song ‘Kill Bill’, but a sped-up version of it. It took me a second to even recognise what it was, and then I was like, who is even getting paid for this? Is this a fan or did the label make this?” says Goldner.

Of course, a major distinction between official remixes released by major labels and DIY nightcore is that the former can legally exist on streaming platforms. But even then, fan edits still manage to slip through; you can often find unofficial sped-up or slowed-down remixes uploaded to Spotify under the podcast section in order to better evade detection.

If you were a fan of nightcore, it was an easy jump to start making it yourself. All you needed were songs on your hard drive and a free sound-mixing program like Audacity or Virtual DJ. The bootleg element gave scenes like these a low barrier to entry; anyone could do it – but this also meant the resulting tracks had little commercial viability, reliant on samples that could probably never be cleared.

It has taken a few years, but the industry seems finally to have figured out how to cash in on both ends of the speed spectrum. Parallel to the “sped-up” remix is the “slowed and reverb” or simply “slow” remix, essentially a low-effort version of chopped-and-screwed, the iconic style of slowed-down hip-hop developed by DJ Screw in Houston, Texas in the 1990s. Producers like xxtristanxo and Ex7stence, who have pivoted from amateur TikTok edits to officially sanctioned major label remixes, often dabble in both styles.

That being said, while there may be growing name recognition for producers within the sped-up scene – xxtristanxo and Ex7stence share over 9 million followers between them – it shares a similar anonymity with nightcore, even at the highest commercial level. Universal Music regularly releases sped-up and slowed-down versions of their artists’ back catalogues. On generic Spotify pages such as “USpeed” and “UChill”, tempo-shifted remixes of everything from Hanson to hair metal to “God Bless the USA” accumulate hundreds of thousands of listens every month – and yet, there is no evidence as to who actually produced them.

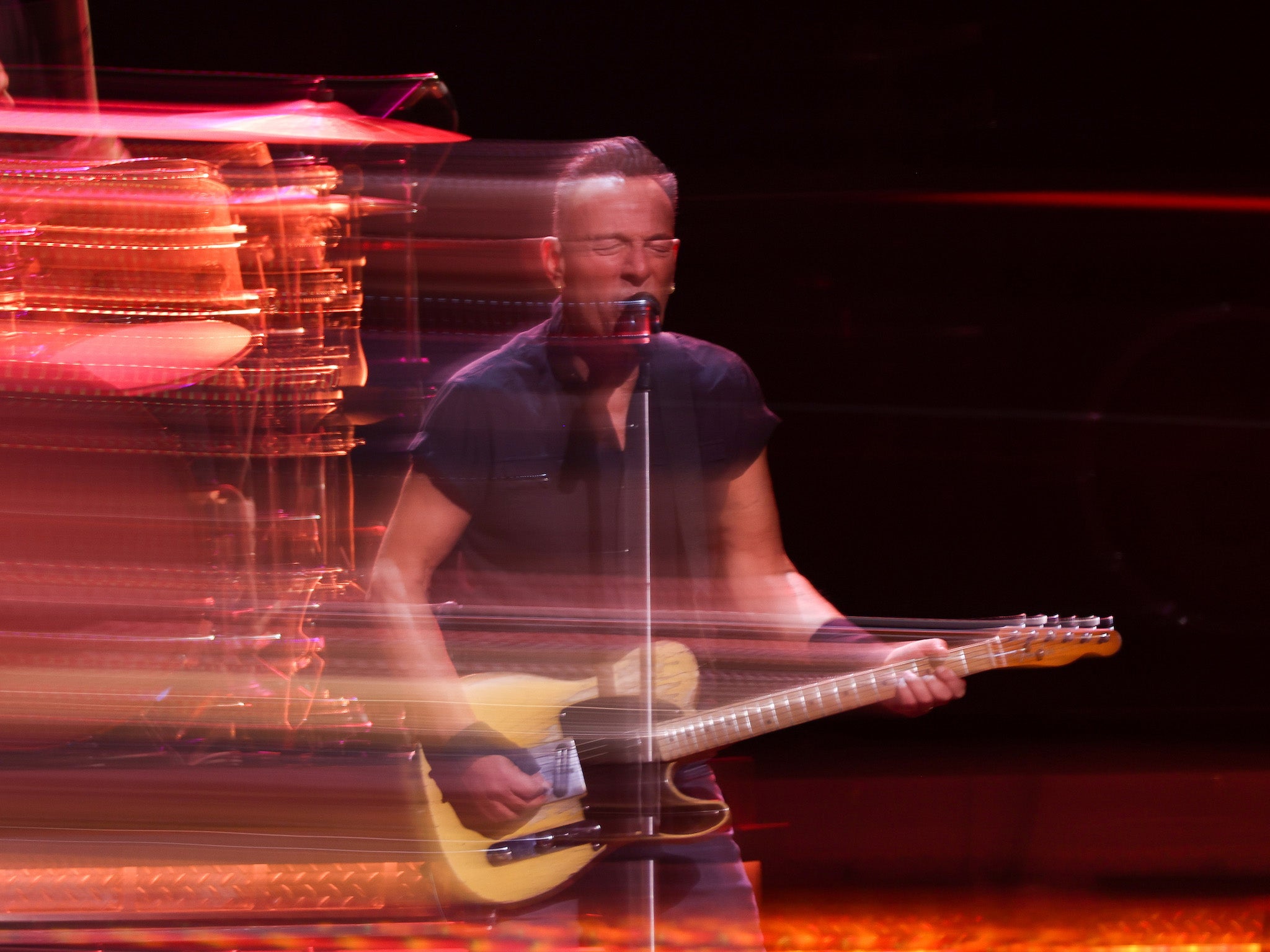

Jaime Brooks is an astute observer of industry trends as a writer, but she also has direct experience with pitch-shifting, as part of musical projects like Elite Gymnastics and Default Genders. A personal favourite of mine is her nightcore-adjacent version of Bruce Springsteen’s “Secret Garden”. After originally uploading it as a bootleg sped-up remix to SoundCloud in the early 2010s, she later recorded her own pitch-shifted cover for the Default Genders album Main Pop Girl 2019.

Pitch-shifting my voice on record is probably because of my desire to escape the classifications that people make based on how my voice sounds

“I got interesting feedback on ‘Secret Garden’ because I had some friends who didn’t realise it was a cover,” says Brooks, whose journey into pitch-shifting began when she discovered a simple Autotune slider on Garageband. “Everybody’s heard that song because of Jerry Maguire, the marketing was so prominent and it was a big radio hit for Springsteen in the late Nineties, so maybe they knew the song before from those contexts, but they had never really listened to it until the sped-up version I did.”

For many trans musicians like Brooks, recording vocals can be a fraught thing. There is a gut reaction to the human voice, she says, that speaks to how innately we’re conditioned to gender people based on their tone and resonance. Altering pitch is a way to queer the voice, to scramble expectations and alter the listener’s engagement with a musician’s identity. “For me, I think pitch-shifting my voice on record is probably because of my desire to escape the classifications that people make based on how my voice sounds. I have not really enjoyed a lot of the feedback I’ve received about my singing over the years, and I wanted to exist outside of that, so I used effects to do that.”

In Brooks’s opinion, the impact of gendered perception on the voice isn’t a new phenomenon, but one that dates back to the origins of recorded music. “Early radio stations would alternate male vocalist, female vocalist, and instrumental, because the idea was that you would have these three types of recordings that would appeal to a different segment of the audience,” she explains. “The only real difference between pop and rock radio stations today is that pop stations are predominantly women’s voices, and rock stations are predominantly men’s voices.

“If there are men’s voices that do fit into pop, it’s usually a higher falsetto, where rock stations have deeper, Imagine Dragons-type voices. Even though music discovery has become more complicated, those instantaneous gut-level reactions people have to the voice that is singing a song still persist.”

With sped-up remixes of songs by female artists, such as Ellie Goulding’s “Lights” or Nelly Furtado’s “Say It Right”, the change is often more subtle because the vocalist’s voice is high-pitched to begin with. But speed up a deeper male voice and it can produce a radical change: dour emo rockers Pinegrove recently scored an unexpected viral hit with a sped-up remix of their 2015 song “Need 2”, which makes lead singer Evan Stephens Hall sound softer and more feminine. And if that wasn’t fast enough for you already, there’s even a “hyperspeed” version of it. “When you speed up certain songs,” says Goldner, “it adds a certain ethereality, or maybe it emphasises the femininity in it.”

Like Brooks, Goldner has experienced the queer potential of pitch-shifting first-hand– whether that is slowing down or speeding up. “I had this thought that maybe at a time in high school I wasn’t very comfortable with my sexuality or my body, so that kind of pure and unadulterated beautiful pop production of Jojo felt inaccessible to me,” says Goldner. “But once you slow it down and make it a little weird, a little ugly, a little imperfect, suddenly you can appreciate that it’s a beautiful melody or chorus, because of the dissonance. Speeding up has a similar effect.”

Part of the popularity of scenes like nightcore and vaporwave lies in how little effort it takes to make something that sounds “new” and eerily beautiful. That ease of access, though, is a double-edged sword, because it is exactly this ease that is allowing the industry to start capitalising so heavily on the potential of pitch-shifting.

For major labels, a sped-up remix isn’t about queering the human voice or generating creative dissonance. It’s about racking up more streams for less work. If you already have a recording on hand, it only takes a couple of clicks to create a sped-up and slowed-down version, potentially tripling the streams you would get from the original alone. “Whether we’re talking about the nightcore era or playing records at different speeds on a turntable, changing the speed of music used to be something the listener had control over,” says Brooks. “The emergence of prefabricated sped-up [remixes] has removed some of the agency and control the consumer used to have. Spotify can’t give you a nightcore button.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks