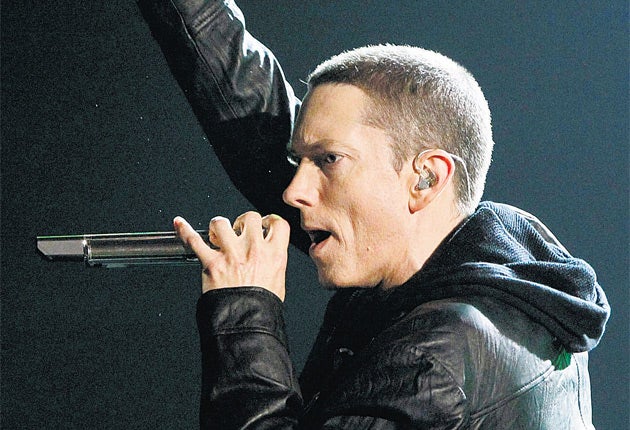

Slim Shady's rap-sheet of relapse and recovery

Eminem soared from drug-filled poverty to adulation and notoriety, and then collapsed into gilded, narcotic, seclusion. But, after his latest comeback, his biographer Nick Hasted believes the future holds plenty for the master wordsmith

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I began writing the first serious biography of Eminem 10 years ago, he was at the height of his powers and notoriety. "Stan", his astonishing shaggy-dog tale of letters between himself and an unhinged fan – somehow made more funny and menacing by the sampled Dido's wan desire for a cup of tea on a drizzly English day – had just been released. Everybody I knew wanted to talk about it, and its singer, and once they started they couldn't stop. This was a rapper who in other songs had decided to kill his estranged Mum, absent Dad and long-suffering wife Kim, claimed to have murdered OJ Simpson and armed the Columbine killers, and, who when attacked for homophobia, rapped: "Hate fags? – yes." He was picketed by feminist and gay groups, baited by homophobic tabloids and liberal broadsheets. Eminem for one moment gave pop back its centrifugal force at culture's core. For the first and, to date, last time, I was offered sex for my ticket when he flew into Manchester to find he'd become a folk devil.

I was soon walking Detroit in his footsteps. The city looked as if it had been dredged from underwater. You could hear the wind whistling through huge roofless factories, and walk for 15 minutes in the city's gutted, once grand, heart without seeing a soul. Pacing down 8 Mile Road, the borderland between black urban Detroit and its white suburbs which he made notorious in songs and an Oscar-winning film, I saw the broken landscape that helped make him great. As Elvis did in Memphis, Eminem – then Marshall Mathers, of course – had experienced life as a minority on the black side of town. And he knew from black friends the bigger American picture. His shattered city made him understand class too; he knew which he was, and rapped for the underdog. The misogyny, beginning with his awful relationship with mother Debbie Mathers-Briggs, and continuing with childhood sweetheart and lyrical punchbag Kim, was more troubling; the homophobia too. But female and gay friends found his articulate rage universal. Sometimes they felt just like him.

He tended to attack rather than retreat when criticised, anyway, as Presidents from Clinton to George W Bush (who called him "the worst thing to happen to American youth since polio") both found. Retaliating to such slurs made him the most brave, articulate anti-government pop star during the paranoid, post-September-11 clampdown. In the year of Bush's 2004 re-election, "Mosh" lyrically decimated the new McCarthyism. In the ultimate battle rap, he called out the President: "Maybe we can reach al-Qa'ida with my speech/ Let the President answer our high anarchy/ Strap him with an AK-47/ Let him fight his own war/ Let him impress Daddy that way... no more blood for oil". Anyone who was in America at that time knows the risks he was taking, which no other pop star did with such directness. Those who've rhetorically wondered where the 1960s- and 1980s-style songs of protest and resistance are now: they were here.

When I thought I'd concluded my book, in 2003, I compared Eminem to Allen Ginsberg: two men big enough to write about America every time they wrote about themselves, and themselves every time they wrote about America. These were, I thought, inexhaustible subjects.

Eminem has turned out to be. Every few years I have found myself coming back to my book, which has grown with its subject. When I began work again for its new edition, it was like picking up with familiar acquaintances; older and apparently wiser, but beneath the surface still just the same. In the spring of 2009, Eminem had not released an album for five years. For the last four, he had disappeared altogether into one of his two cavernous mansions on the outskirts of Detroit. There he lived anonymously with daughter Hailie, his half-brother Nate (14 years his junior) and adopted daughters Alaina and Whitney, both from Kim's family.

He'd briefly surfaced in the unlikely pages of Hello! to marry Kim for a second time on January 14, 2006; they lasted 41 days. His lyrics' misogyny had, anyway, long ago been outweighed by the exasperated affection that peeked through them for a woman he couldn't live with or without. In the same way, his homophobia had melted under his contact with a wider world, not least in his unlikely friendship with Elton John. The essential decency I'd discovered in his private life (a soft-spoken, considerate existence, the opposite of his more hateful lyrics) seemed to have doused the rage his work flared from. As he became rap's Howard Hughes, hidden away on vast estates, his movements unknowable, insiders said he was rapping every day. What sappy nonsense would it be?

But behind those gates, Eminem had not become contentedly successful. He was instead sinking towards suicidal rock-bottom. He had constantly railed on record against his mother's alleged addiction to prescription drugs and childhood feeding of them to him. But now, with the active assistance of the sort of compliant "Dr Feelgoods" who fed Elvis his pills, he was gulping 20 Vicodin a day. He lost count of the Ambien and Valium, and soon was trying other things too.

He had been dabbling for years, accounting for some of the mush-mouthed, stumbling raps on Encore (2004) and the hits collection Curtain Call (2005). The excuse to go deeper had come on April 11 2006, when Proof, rapper and best friend since adolescence, was shot dead in the small hours, in the last bar open in the sort of rough Detroit neighbourhood Eminem had retreated from. Pistols had been pulled. When the bullet-smoke cleared, Proof and ex-Marine Keith Bender were dead.

"His death brought me to my knees," Eminem later said. Some days when the rapper opened his mouth he made no sense. Some days, he couldn't walk. The shock had spread right through him. That was when the mansion gates slammed shut, and pills began to be stockpiled in porn-video cases where his daughters wouldn't look, among other addicts' tricks. Marshall Mathers had shown iron will to haul himself up from an unstable family background and near-destitution to become Eminem. Now, when the kids had gone to school, he'd sit half-dressed on the sofa, wondering when the first naked breast might appear on TV. He watched the Rocky films and Boogie Nights 150 times each, comforted by familiarity. It was true he rapped in his home studio each day. All but one of these hundreds of recordings (the desperate "Beautiful") was doggerel. The man who read a dictionary as a child and obsessively filled notebooks with astonishing words couldn't write. In December 2007, he took blue pills he'd not seen before. He fell and woke in an ambulance. "They say if I had got to the hospital two hours later I would be gone," he later remembered with horror.

Back home, he gulped more drugs. But, on April 20, 2008, he took his last pill. He trained at a boxing gym just like Rocky. Slowly, he started to write again. He went down to Dr Dre's studio in Orlando, Florida. He had taken several mortifyingly unproductive trips there before, and feared failing in front of his old friend again. They blazed through 11 tracks, which he finished in a new Detroit studio.

Relapse (2009) was the result. It had the brilliantly agile word-play of a man giddy with delight that he can rap at all; the jig you give when you throw crutches away. But the words were superficial, as was the album's impact. So he went back, and wrote last year's five-million-selling Recovery. There he wept over Proof, and exposed every raw nerve the pills had numbed. On "No Love", he let the current rap king Lil Wayne guest. Ramping up his skills to warp-drive, Eminem more than matched him. This was his real comeback, after half a decade of darkness.

Eminem at 38 has changed, as the isolation of his American fame has deepened. He writes about himself much more than his country now. Maybe he isn't like Ginsberg. But his commitment to renewing his astonishing talent, and the intense dramas of his life, are as bottomless as I first hoped. I'll be going back to my book.

'The Dark Story of Eminem', Nick Hasted's updated biography, is out now (Omnibus Press)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments