‘She was deemed mad and unpredictable’: The day Sinead O’Connor tore up a photo of the Pope on Saturday Night Live

Thirty years ago, a young Sinéad O’Connor shocked America with her political protest on ‘Saturday Night Live’. She was promptly banned for life by broadcaster NBC, pelted with eggs in the street and booed during live shows. Ed Power reflects on the impact of that night and the contrasting reactions in the US and Ireland

This article is being reshared in light of Sinead O’Connor’s death, aged 56

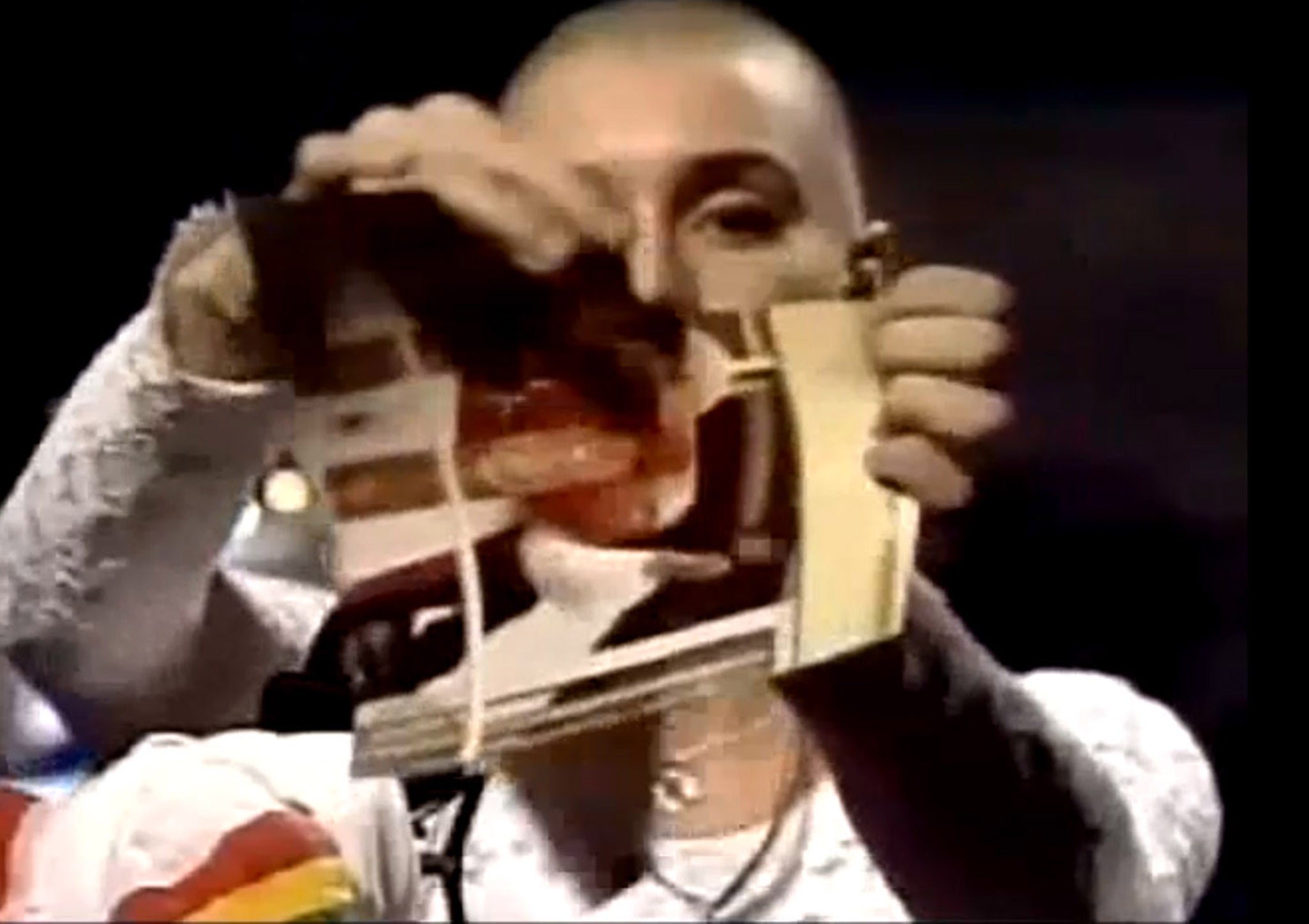

Her green eyes gleaming with determination, Sinéad O’Connor stares into the cameras at the Saturday Night Live studio – in the bowels of the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan – and holds a photograph in front of her face.

Nobody blinks or says a word. Around her, the backstage bustle continues uninterrupted. The picture is of a Brazilian street child shot dead by police death squads. It’s 3 October 1992 and O’Connor is rehearsing her cover of Bob Marley’s “War” for her performance on SNL that night. The child’s photo is a calculated distraction. For her real appearance, she’ll proffer another image entirely. And the response will be very different. Thirty years on, it remains a defining moment in the Irish singer’s life and career.

“I sing ‘War’ a cappella. No one suspects a thing,” O’Connor recalled in her 2021 memoir, Rememberings. “But at the end, I don’t hold up the child’s picture. I hold up John Paul II’s photo and then rip it into pieces. I yell, “Fight the real enemy!’” Her words hung in the air as she blew out the candles set on a table to one side. Darkness descended, in more ways than one.

NBC immediately banned O’Connor for life. Outside the studio, on that warm Manhattan night, passers-by pelted her with eggs. At a Bob Dylan tribute concert in Madison Square Garden a fortnight later, she was booed (the noise mingled with shouts of support). Putting an arm around her, Kris Kristofferson told her not to “let the bastards get her down”.

With jeers ringing out, she sang “War” again (the track was the centrepiece from her just-released covers record, Am I Not Your Girl?). “Until the colour of a man’s skin is of no more significance than the colour of his eyes/Me say war,” O’Connor intoned, her voice cracking. The chorus of disapproval only grew louder. Her plea for racial solidarity was received by New York as a taunt. “Half [of] them are booing, half [of] them are cheering. It’s the weirdest noise I’ve ever heard in my life,” O’Connor explains in Nothing Compares, Kathryn Ferguson’s new documentary about O’Connor’s life and times (released 7 October). “It makes me want to puke.”

Just two years earlier, O’Connor had received an altogether different reception in America. She had vaulted to the top of the US charts with “Nothing Compares 2 U”, her unfiltered cover of an obscure Prince track. In the video, she cried over the memory of her late mother, who died in a car crash in 1985.

Marie O’Connor was also the “inspiration” for her daughter’s Saturday Night Live protest. The two had a difficult relationship: O’Connor accused her mother of traumatising her physically and emotionally during her childhood. After Marie’s death, O’Connor took down a portrait of the Pope from the wall of her house in Dublin. This was the image she smuggled into the SNL studios. Was the “real enemy” her abusive parent, rather than the Bishop of Rome?

When you’ve outraged Madonna, you know you’ve touched a nerve

Whatever her motives, America was scandalised. “Holy Terror!” ran the front-page headline of the New York Daily News. Joe Pesci, a devout Catholic, said he would “have given her such a smack” when he hosted SNL the following week. Even Madonna – the mother superior of scandalous pop stars – criticised O’Connor. “I think there is a better way to present her ideas rather than ripping up an image that means a lot to other people,” she said. When you’ve outraged Madonna, you know you’ve touched a nerve.

Back in Ireland, the response was more muted. One reason was that the footage of O’Connor was not widely seen. Saturday Night Live had a negligible cultural imprint (to this day, its groaning, immature humour remains lost in cultural translation). And it wasn’t as if you could seek out the clip on YouTube. The scandal came and went largely unnoticed. There was a second factor, however. Public opinion in Ireland was slowly yet inexorably turning against the Catholic Church. The floodgates were straining. Within a few years, they would burst, the country swamped in clerical abuse scandals.

The turning of the tide had already begun by autumn 1992. In May of that year, the standing of the Irish Catholic Church had been fatally undermined by the revelation that Bishop Eamonn Casey – a familiar face on the airwaves – had fathered a teenage son during an affair with an American in the 1970s. Far from provoking people back home, O’Connor had tapped into a gathering storm of anger. Where she had gone – publicly rejecting the Church and its hypocrisies – an entire country would soon follow.

“There had been no dismantling of the power of the Church in America. The Catholic Church there was still very much revered,” Dr Finola Doyle O’Neill, a broadcast and legal historian at University College Cork, tells me. “It wouldn’t be [dismantled] until 10 years later, in 2002, with the Boston Globe revelations [about the cover up of clerical abuse in New England]. We in Ireland were a decade ahead in terms of dismantling the Church. In 1992 there would have been the big revelation about Bishop Eamonn Casey. Slowly but surely, there was a slow drip-drip of the release of the hold of the Catholic Church.”

But if O’Connor would ultimately be vindicated, in the short term the impact was devastating. She was dismissed as unhinged, in the way that women who speak out have been since the dawn of time.

“The fact that she was right to rip up the picture of the Pope and expose the harsh realities of what was going on behind closed doors was irrelevant. She was deemed mad and unpredictable, causing the end of her career,” says Linda Coogan Byrne, a music publicist who has researched gender disparity in radio playlists in Ireland and the UK. “O’Connor became an oft-parodied figure in popular culture. Every time she spoke out, which is what many artists do, she was at risk of being cancelled. All we have to do is look at all the male artists who have had a slap on the wrist and then go on as normal. When it’s a woman, it’s utterly damning. Women with something to say are always deemed a dangerous thing.”

As alluded to above, O’Connor’s motivations for ripping up the picture were complex and personal. Born in 1966, she had grown up in an Ireland where, if the Church’s days were numbered, women remained marginalised. Catholic Ireland had reached its apotheosis in 1979, when Pope John Paul II became the first pope in history to visit Ireland. O’Connor, who was 13 at the time, will have remembered the mass outpouring of emotion all too well. The pope’s trip was Ireland’s equivalent of Britain following the death of Diana. A mania descended upon the country.

But, as pointed out already, Church misogyny wasn’t O’Connor’s only target. She had a traumatic relationship with her mother, who “stripped and kicked” her as a child. “My mother was a very violent woman. Not a healthy woman at all,” O’Connor said in Nothing Compares. “The cause of my own abuse was the Church’s effect on this country. Which had produced my mother. I spent my entire childhood being beaten up because of the social conditions under which my mother grew up. I would compare Ireland to an abused child.”

Marie died when her car skidded on black ice and collided with a bus in a suburb close to where her daughter had grown up in south Dublin. She was 45 and had been driving to mass. Afterwards, O’Connor removed just two items from her house: a cookbook and that portrait of John Paul II. “I took down from her bedroom wall the only photo she ever had up there,” she wrote in her book. “Pope John Paul II. It was taken when he visited Ireland in 1979.”

On the night of the broadcast, O’Connor had arrived at the Rockefeller Centre in a confused frame of mind. She’d been living in New York on and off for several months and had struck up a friendship with a Rastafarian named Terry, whom she met at a juice bar. But shortly before the rehearsals, he’d told her that his real job was as a drug smuggler, and that he had used children as “mules”. He also claimed that he had been targeted for assassination by a rival dealer (he would be shot dead soon afterwards).

O’Connor was upset. But she nonetheless went about smuggling in the image of the pope with impressive efficiency. “I bring the photo to the NBC studio and hide it in the dressing room. At the rehearsal, when I finish singing Bob Marley’s ‘War’, I hold up a photo of a Brazilian street kid who was killed by cops,” she wrote. “I ask the cameraman to zoom in on the photo during the actual show. I don’t tell him what I have in mind for later on. Everyone’s happy. A dead child far away is no one’s problem.”

Then came showtime. She went on in a lacy white dress that once belonged to the singer Sade, which O’Connor had acquired in a London flea market for £800. She first performed “Success Has Made A Failure of Her Home” (her take on Loretta Lynn’s Success). It went down a storm. “I’m the flavour of the month. Everyone wants to talk to me,” O’Connor wrote of that moment. “Tell me how I’m a good girl. But I know I’m an imposter.”

Next, it was time for “War” – and the ripping of the Pope’s image. “Total stunned silence in the audience,” she said of the reaction. “And when I walk backstage, literally not a human being is in sight. All doors have closed. Everyone has vanished. Including my manager, who locks himself in his room for three days and unplugs his phone.”

In a way, America had been looking for an excuse to turn on O’Connor. There had been an uproar in August 1990 when she refused to allow the US national anthem to be played before her concert in New Jersey. She’d gone on to boycott the 1991 Grammys in protest at America’s wars in the Middle East and urged her fellow artists to follow her example.

Pope-gate was the end of O’Connor as a commercial force in America. She never again troubled the charts or performed on primetime TV. But in Ireland, she inspired a generation of female artists who finally had someone to look up to – singers such as Dolores O’Riordan of The Cranberries and Róisín Murphy who, like O’Connor, refused to let the industry tell them what they could or could not do.

O’Connor herself never wavered in her feelings about the incident. She was proud of her actions. “A lot of people say or think that tearing up the pope’s photo derailed my career,” she wrote in her memoir. “That’s not how I feel about it. I feel that having a No 1 record derailed my career and my tearing the photo put me back on the right track… Far from the pope episode destroying my career, it set me on a path that fit me better.”

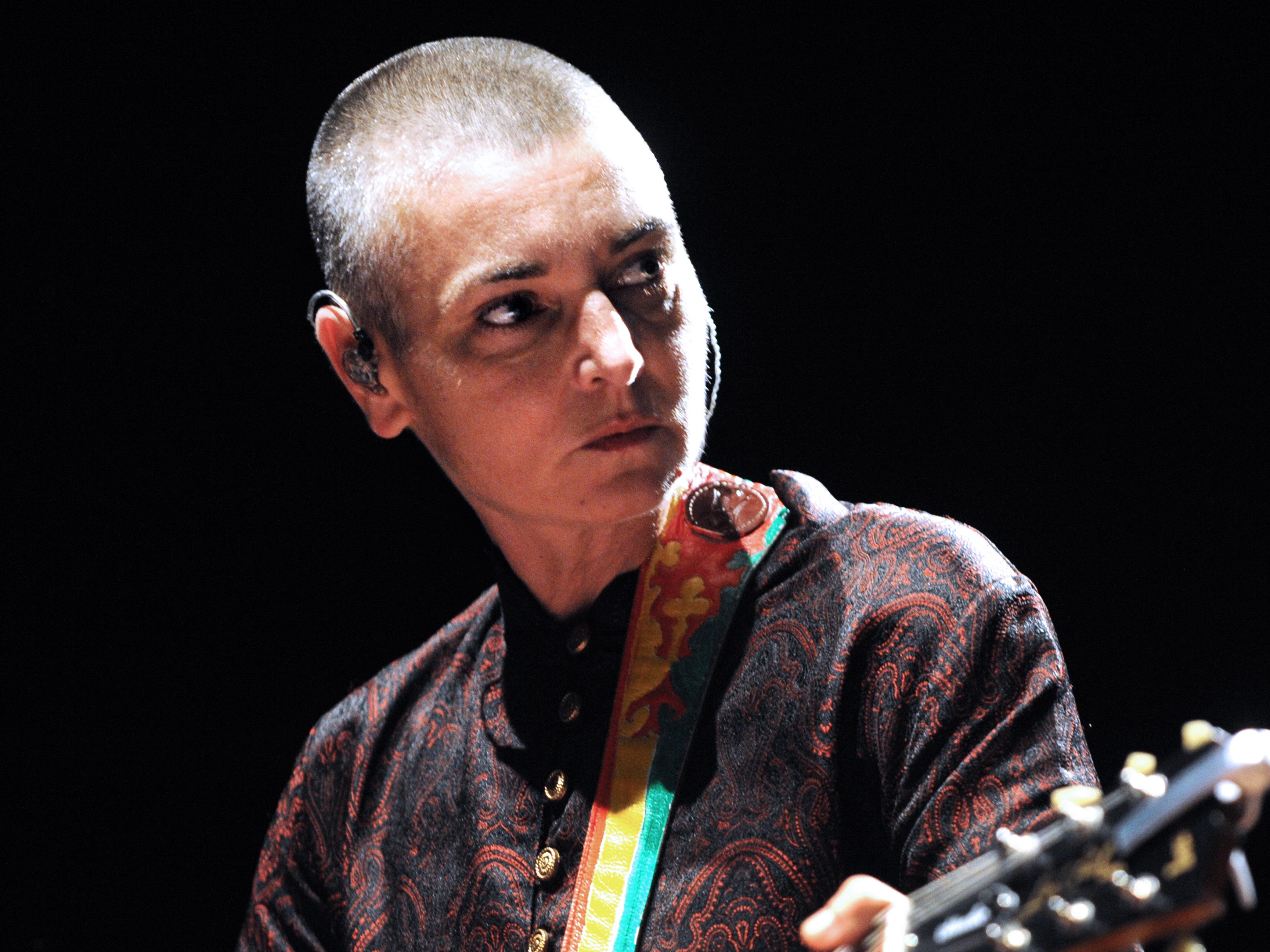

Her life has since been beset by tragedy. But her ferocity as an artist never dimmed. I last saw her perform at a festival in Tipperary in 2019. Halfway through, she reached for Nothing Compares 2 U, the song that had changed everything and brought her the success she never craved.

She sang with her eyes closed, beneath the cold sky in a slightly run-down stadium far from the bright lights of New York. Under the stars, a long way from the spotlight, she seemed, just for a moment, at peace.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks