Satanism and The Rolling Stones: 50 Years of ‘Sympathy for the Devil’

When Mick Jagger sang ‘Just call me Lucifer’, pop music changed forever, but the tragedy of Altamont lay ahead, writes Simon Hardeman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fifty years ago this week Mick Jagger became the Devil. Everyone had known the Rolling Stones were misogynistic, drug-taking, all-round bad boys but as he sang, “Please allow me to introduce myself / I’m a man of wealth and taste…” the genie – or, rather the demon – bolted from the bottle. The results would be devastating. For pop, it laid a new path for some of the biggest bands ever, but for the Rolling Stones it led to a vicious murder at an infamous concert exactly a year from the song’s release, and an abiding reputation for evil.

The song was “Sympathy for the Devil”, the opening number on the Beggars Banquet album, both released on 6 December 1968. The Stones’ previous LP had been Their Satanic Majesties Request. Its occult pretensions pretty much began and ended with the title, but it was a sign of something coming. Stones guitarist Keith Richards’ lover Anita Pallenberg, with whom Jagger had a steamy on-set relationship during shooting of the film Performance earlier in the year, was said to wear anti-vampire garlic round her neck and keep voodoo-style bones in a drawer; American filmmaker and occultist Kenneth Anger wanted Jagger to play Lucifer in a film he was making; and, as the peace-and-love era drew to a close, the dark side had become increasingly attractive to pop musicians. Occult legend Aleister Crowley had appeared on the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper, and there was even a diabolic track in the charts on the day of the song’s release – Gun’s “Race with the Devil”.

But what seems to have been the key inspiration for songwriter Jagger (it is his only solo masterpiece, according to his biographer Philip Norman) was when his girlfriend, Marianne Faithfull, gave him The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov’s long-suppressed and recently translated Russian novel in which the Devil appears in Moscow and creates murder and mayhem. “Sympathy” has many lines that mirror Bulgakov’s book – including the way the debonair Devil presents himself, and passages about Jesus’s crucifixion.

Jagger had written “Sympathy” as “sort of like a Bob Dylan song”, he told Rolling Stone’s Jann Wenner in 1995. But during recording, guitarist Keith Richards suggested its trademark samba beat. Jagger said this had “a tremendous hypnotic power… because it is a primitive African, South American, Afro-whatever-you-call-that rhythm. So to white people, it has a very sinister thing about it.”

And over this insistent, primal rhythm he personified Satan in an extraordinarily uncompromising, gloating way – “I was ’round when Jesus Christ / Had his moment of doubt and pain / Made damn sure Pilate / Washed his hands and sealed his fate… / I stuck around St Petersburg / When I saw it was a time for a change / Killed the Tsar and his ministers / Anastasia screamed in vain”. And, in case anyone doubted where he was coming from, he sang “Just call me Lucifer”. The original title of the song had been “The Devil Is My Name”.

Musicians and artists had played with devilry before but for pop this was something else. Jagger WAS the Devil! Richards told Rolling Stone: “Before, we were just innocent kids out for a good time.” But after “Sympathy for the Devil”, he said, “they’re saying, ‘They’re evil, they’re evil’… There are black magicians who think we are acting as unknown agents of Lucifer and others who think we are Lucifer.”

Jagger was taken aback by the effect. “It was only one song. It wasn’t like it was a whole album, with lots of occult signs on the back,” he said, 20 years later. He was amazed how “people seemed to embrace the image so readily, and it has carried all the way over into heavy metal bands...”

He had opened Pandora’s Box, according to musician and occultist Kieran Leonard. “It kicked down the door for diabolism in the mainstream,” says Leonard, whose forthcoming book investigates the esoteric and creativity, and whose music with his own band, St Leonard’s Horses, is inspired by this passion. He admits a fascination with the darker side was “in the air” then, but says “Sympathy for the Devil” was the key moment, “the pin-prick in the time map”.

And then, a year to the day later, came the moment that confirmed the Stones’ new reputation. It was what one reporter called “rock’n’roll’s all-time worst day”. At their chaotic free concert at the Altamont Speedway in California an African American teenager with a gun was knifed to death by Hells Angels to whom the Stones had contracted security. Popular belief, fuelled by bad reporting, was that the murder happened as the band were playing “Sympathy for the Devil”. Though trouble seemed to start during that song, it was actually a few numbers later that Meredith Hunter was stabbed. Nevertheless, accused of “diabolical egotism” by Rolling Stone magazine, and stunned by the general outcry, the Stones didn’t play the number live again for several years.

They might have been warned off, but others were not. Black Sabbath formed in 1969, aiming to create the musical equivalent of horror films. Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page was inspired by Aleister Crowley, opened an occult bookshop, and a line of Crowley’s was written into the vinyl of Led Zeppelin III. David Bowie incorporated occult inspiration into his music all the way from “Quicksand” on Hunky Dory to his final album. The list of hard rock and heavy metal bands who have dabbled in and drawn on the occult is a long one, from Black Widow’s chilling early-Seventies “Come to the Sabbat” to Iron Maiden’s “The Number of the Beast” to Marilyn Manson to the welter of contemporary metal bands with names such as Evil Empowered, Make them Suffer, Black Rites in the Black Nights, Black Wedding, The Devil Inside, Pop Evil and Black Soul.

As rock’n’roll frontman Jim Jones of the Jim Jones Revue says, Satan is now “an easy go-to, a one-stop shop for distancing yourself from everything ‘good white Christian’” though, for him, occultism and Satanism represent esoteric knowledge –“always the smart choice, whatever the consequences”.

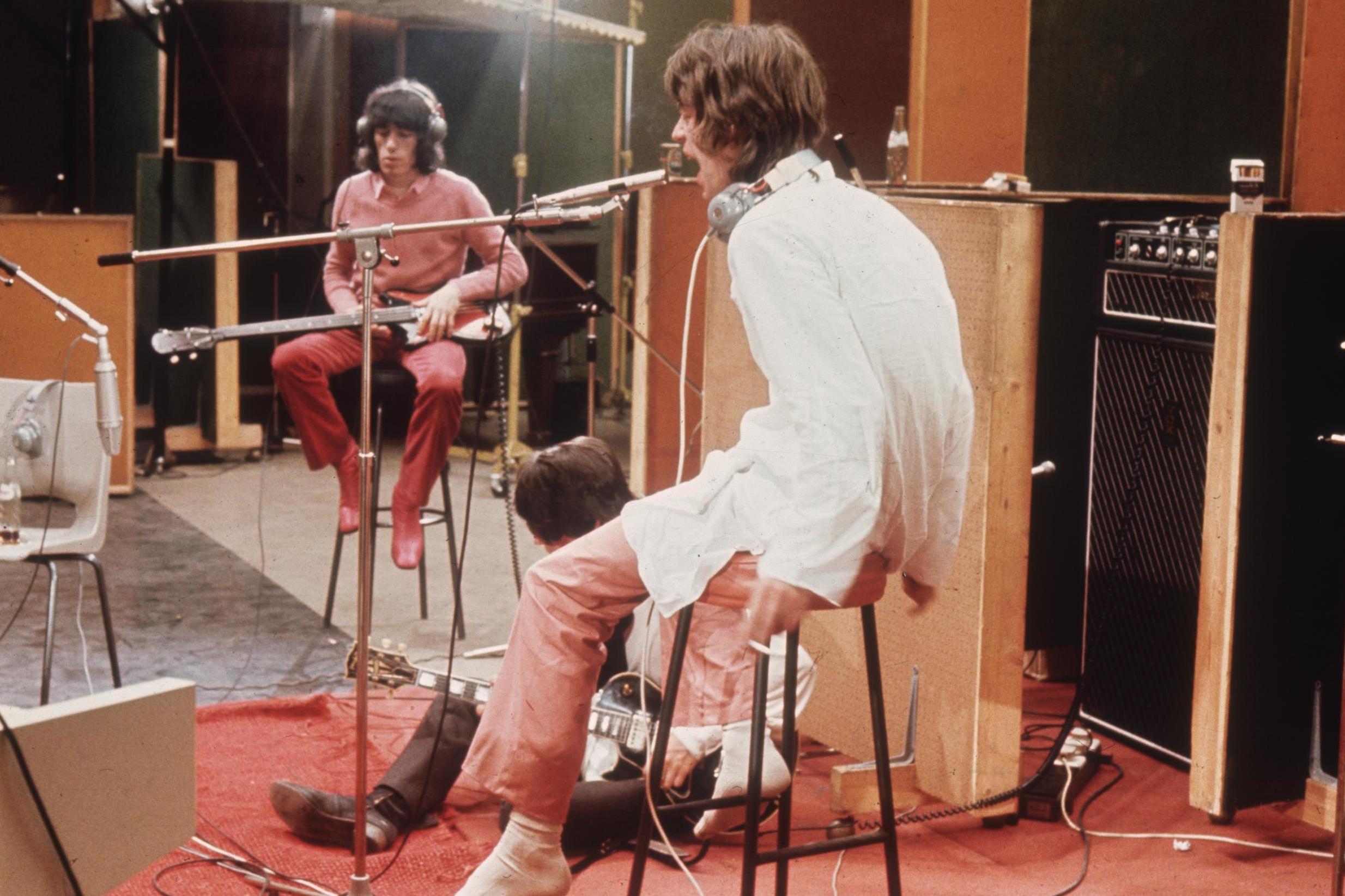

There are three fascinating films about “Sympathy for the Devil”. Jean-Luc Godard’s otherwise borderline-unwatchable film of the same name documents the recording session, the first time audiences had been able to see a major band creating a track in the studio in such a way. The Altamont gig is the jaw-dropping centrepiece to the Maysles brothers’ movie Gimme Shelter. And just five days after “Sympathy” was released, Jagger was captured performing the song for the film The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus. It’s still shocking today, when the “devil’s horns” hand gesture is commonplace in the mildest of music, to see him pull off his shirt at the end and reveal the horned head on his chest.

Or maybe the Devil had been underneath all along.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments