Re-start me up: Is this The Rolling Stones’ last chance to make another great album?

As the legacy rock band prepare to launch a new album, The Rolling Stones are the latest of several acts to look at their seventies and beyond as an opportunity to start over. Ed Power looks at how the legends use old age as a chance to be young again

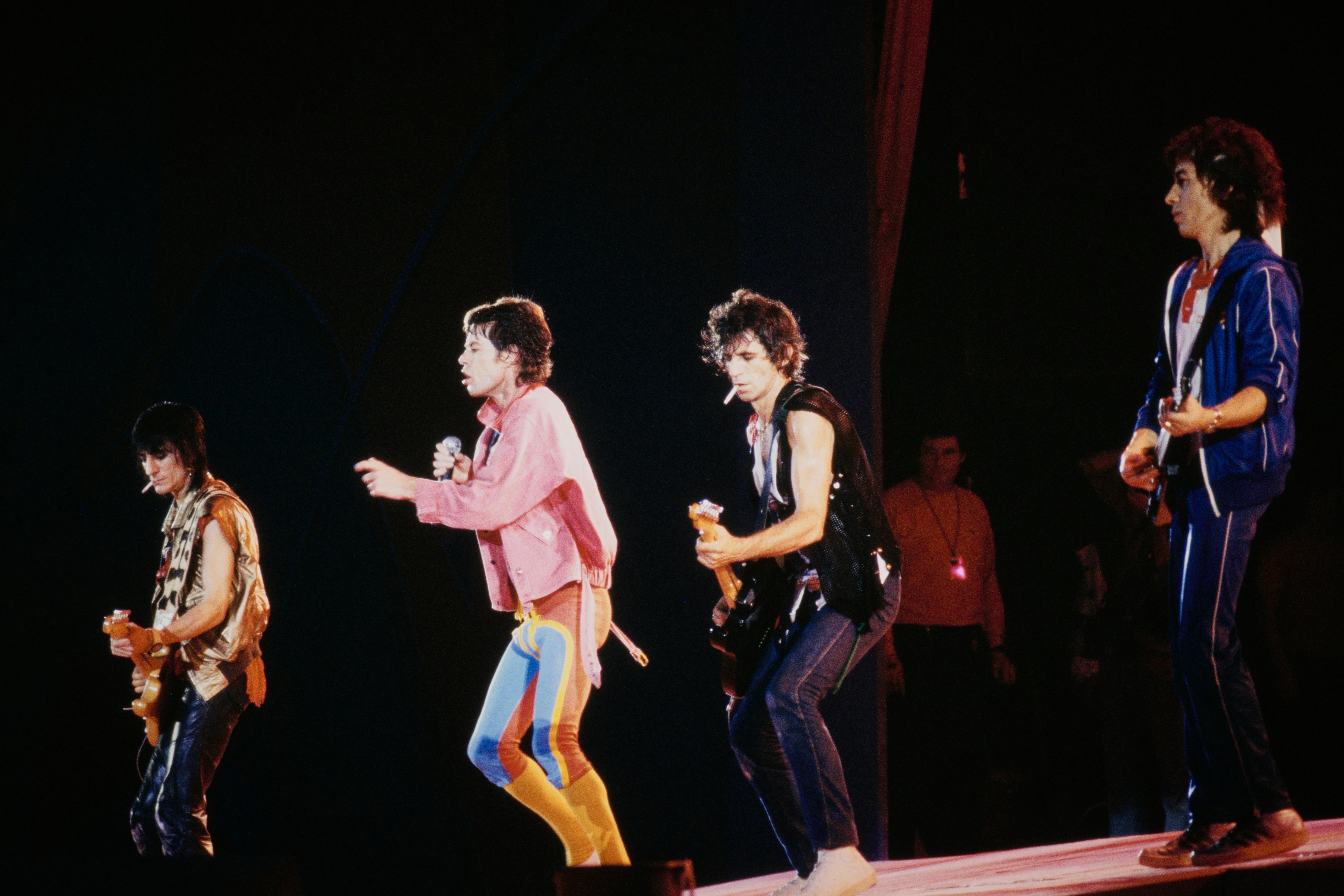

The Rolling Stones’s comeback single, “Angry”, is not a song haunted by the possibility of failure. It is full-throttle Mick and Keef karaoke, with its “Start Me Up”-ish riffs and a video mainly consisting of the camera hugging the bum of Sydney Sweeney – the zeitgeisty star of cult TV shows Euphoria and White Lotus – as she drives around Los Angeles.

At first blush, then, it’s a relatively predictable return from this crumbling Mount Rushmore of classic rock (whose fourth pillar, drummer Charlie Watts, passed away two years ago). Most Stones fans have despaired of the group ever regaining the monstrous creativity that powered them through the Sixties and Seventies. On hearing this formulaic retread, they might be tempted to – yet again – abandon all hope as they look ahead to the accompanying LP, Hackney Diamonds, due 20 October.

But to write off the album would be premature. Jagger has gone out of his way to promise that this set of new songs will be special – implying, after 40 solid years of undercooked Stones records, that it might be different this time. (1981’s Tattoo You is considered their last essential cut, despite being a collection of older, semi-completed outtakes hastily stitched together in the studio at the last minute). “I didn’t want to make an album that was just an assembly of what we had done over the past five years,” Jagger said in a new interview. “Three good tracks, five OK, three mediocre”.

Could they be the latest ageing megastars – following Johnny Cash, David Bowie and others – to pull one more classic out of the hat? The clock is counting down in earnest for these craggy legends, yet for rock stars approaching the end, old age is a chance to be young – and great – again.

In other words, now that Jagger’s hit 80, suddenly, it’s all about the quality again for him and his fellow age-defying desperadoes Richards (79) and Ronnie Wood (76). These noises are hugely positive. They suggest that, having got behind every other cliché in rock music, the Stones might be about to tick off one more by releasing, deep in their twilight, a career-defining new LP.

One of rock’s enduring myths is that it is fuelled by youthful vitality. Whether it’s the Beatles and Stones in the Sixties, a whey-faced REM in the Nineties or a pre-cocaine meltdown Oasis, the consensus is that musicians produce their best art young and full of swagger.

But it is just a myth – particularly where iconic acts are concerned. Step back, observe the lifespan of a musician in its totality, and a different trajectory comes into focus. It is one where the rush of youthful enthusiasm gives way to middle-age bloat: think Bob Dylan’s toe-curling Christian trilogy of the late Seventies, Macca in his dad jumper singing with frogs and Rupert Bear on “We All Stand Together”, Liam Gallagher doing whatever he was with Beady Eye.

But, as old age claws into an artist, a second flowering often manifests. Rounding the bend, spotting the finish line, they shake off the inertia and plug back into the qualities that made them beloved. The lethargy of middle age falls away.

If the Stones wanted examples, as they convened in the studio with producer Andrew Watt, they didn’t have to look far. The past 20 years, in particular, have seen “legacy” artists increasingly look on their sixties, seventies and beyond not as a retirement – but, essentially, a chance to start over.

This trend is particular to rock, it should be acknowledged and largely confined to male artists. Blues, jazz and folk musicians have a longer tradition of carrying on for as long as possible. And it has yet to spread to pop – as seen from the appalling ageism directed at Madonna, who has had the nerve to continue recording past age of 50 (though the reaction would, you suspect, be different were Kate Bush to put out a new LP).

In rock’n’roll, the idea of late life as a purple patch arguably coalesced in the Nineties around Johnny Cash. In 1993, country’s Man in Black was 61 when Def Jam producer Rick Rubin (Beastie Boys, Red Hot Chili Peppers) approached him about working together. Nobody today thinks of 61 as ancient. Thirty years ago, things were different. Cash felt washed up and irrelevant: his race was run.

“He didn’t know who I was, but he wanted to understand why I would want to work with him because why would anyone want to work with him? In his mind, he was done,” Rubin would say.

I didn’t want to make an album that was just an assembly of what we had done over the past five years

Cash believed his relative seniority disqualified him from making interesting music. Rubin had the opposite view. Cash’s voice had matured into a care-worn rumble. Across the four albums he would make with Rubin, that voice would prove the perfect vehicle for haunting interpretations of Depeche Mode and Nick Cave. And most famously, Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt”, which the duo tackled on 2002’s American Recordings IV: The Man Comes Around – when Cash was 70, and a year before his death. Listening to his take on Trent Reznor’s stately howl of despair, it’s clear that he had been thinking about life, legacy, and the end of it all.

“I thought of the image of Johnny Cash as the mythical man in black, and any song he sang had to suit this mythical man in black,” Rubin said. “And one of the ones that seemed to have resonated with people after we did it was the Nine Inch Nails song “Hurt”. And if you listen to the words, it’s like looking back over a life of regret and remorse.”

Cash’s late records speak to us because they capture something universal – much as the outpourings of young rock bands do. We’ve all been fresh-faced and keen to take on the world – that’s why “Live Forever” by Oasis chimes with each new generation. But nobody can empathise with Liam and Noel’s Rolls Royce-in-the-swimming-pool overload of Be Here Now. They’re no longer one of us – their daily experiences of excess and privilege too far removed to speak to the listener at anything other beyond a visceral level of third-hand thrills.

Old age, by contrast, gets to us all. Has David Bowie ever been more relatable than on 2016 swansong, Blackstar, released three days before the announcement that he had died from cancer at a relatively young 69? Bowie had been a rock star in high orbit throughout his career – kooky, quiffed, a charismatic weirdo in a sharp suit. Yes, he had his embarrassing dad phase in the Eighties – but even then, he gave us Labyrinth. Yet, in the end, even he was mortal. “Blackstar” lands like a premonition of the deathbed on which we will all one day find ourselves. The drawing of the shutters had made a human of Bowie, pop’s ultimate alien.

Might it do the same with The Rolling Stones? Thus far, they’ve lived out their supposed pensioner years like students looking forward to a free bar. Not even the death of Charlie Watts seemed to have detained them unduly – they spoke movingly about his legacy at their Hackney Diamonds press conference (he is on two of the new tracks). But his replacement, Steve Jordan, has slotted in seamlessly, they explained from their public interview at Hackney Empire. Rather than looking back, the Stones roll ever onward.

Jagger, in particular, seems to have a deep dread of pausing to reflect. And he’s the one ultimately setting the tone. To quote Richards this week, Jagger “is the controller – and I’m the madness”. “That is Mick’s whole thing: let’s do it,” said the guitarist to the world’s media. “In this instance, it was the right time to put the boot behind us and get going.”

The singer has revealed that the new LP will, oh dear, contain a “high energy” dance number, which he insisted on over the vague objections of his bandmates. Still, Jagger is nothing if not canny and surely understands that a new Stones album is one of the group’s few remaining opportunities to remind the world they’re more than an unstoppable touring machine. Early feedback on Hackney Diamonds suggests they have achieved just that: reviewers have gushed about the “pared-back blues numbers, bucolic country-rockers and lighters-aloft pop-rock ballads”, and proclaimed it their most sparkling moment in decades.

The Stones leave nothing to chance. Whether repurposing African-American rhythm and blues for white kids in the Sixties or inventing stadium rock in the Seventies, they’ve always had a thumb on the pulse of rock music. It won’t have escaped their attention that old age is increasingly a period of renewal for rock bands – a time to dig deep and conjure one more classic. Who knows – they may have even made one of their own.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks