Rock's Faustian pact with the theatre

From Mamma Mia to Jersey Boys, the stage is awash with kitschy jukebox musicals inspired by pop bands. But Damon Albarn's Monkey kicked off a credible age for the rock musical, as new works from Tori Amos, Fela Kuti and Sparks now show. Andy Gill reports

Mamma Mia!, We Will Rock You, Jersey Boys – everywhere you look, rock musicals are thriving. Indeed, according to some , they are about the only productions keeping theatres open, as audiences crave the warm embrace of the familiar to get them through hard times.

The theatre isn't the only medium being saved by rock musicals, either. As the music industry struggles to get to grips with the implications of download culture, performers with any length of service and substantial back catalogue are scrambling to boost their balance-sheets by following Abba, Queen and The Four Seasons in knocking together some flimsy narrative that might serve as a unifying theme for a theatrical presentation of their greatest hits. These productions have become known as "jukebox musicals", but a more apt description might be "pop stars' pension plans".

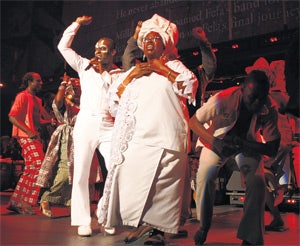

But while the jukebox-musical route is proving profitable for an older generation of rockers, there's a tranche of younger performers whose theatrical aspirations are being realised in more intriguing form. Damon Albarn, most ambitiously, brought the pan-cultural spectacular Monkey: Journey To The West to the stage in 2007, with resounding success; and Rufus Wainwright, never knowingly under-exposing his ego, followed Monkey to the Manchester International Festival with his opera Prima Donna. Tori Amos has been collaborating for the past year or two with Australian playwright Sam Adamson on a musical adaptation of George MacDonald's fairytale The Light Princess for the Royal National Theatre; and multi-tasking A-list stars Will Smith and Jay-Z became successful theatrical producers when Fela!, the musical about Fela Kuti, which they helped bring to the stage, was acclaimed as one of 2009's most vital new Broadway hits. And recent weeks have brought us Sparks' musical radio-play The Seduction Of Ingmar Bergman, in which the absence of staging imperatives has allowed the Mael brothers to make vivid use of evocative musical cues to drive along its narrative. Even former Busted singer James Bourne has dipped his toe into the theatrical pond, his musical Loserville having had a short run in Bracknell, in preparation for moving to the West End.

Not long ago, the term "rock musical" was a weasel phrase employed to varnish what were effectively just common-or-garden musicals with a sheen of youth. By the late 1960s, musicals, along with cabaret, had become tainted by association with an older generation of showbiz operators whose greatest desire was to see their pop-star clients metamorphose into "all-round entertainers". This was exactly the route that Colonel Tom Parker had imposed upon Elvis, with catastrophic consequences for his rock'n'roll reputation, and, in the wake of The Beatles, rock stars correctly surmised that they had no need to follow such an ignominious path themselves.

Teenagers now favoured their own milieu of clubs, concerts and discos over fusty old theatreworld. Hence the invention of the rock musical, with songwriting and production teams desperately trying to lure the young back to the theatre by claiming that the likes of the ridiculous "tribal love-rock musical" Hair had some vital, authentic connection with youth – although it was clear that songs such as "Aquarius" had more in common with jamboree singalongs than rock'n'roll, however naked the singers. But the term "rock musical" quickly caught on, and for years afterwards, productions such as Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar ensured that the staged rock musical was the preserve, not of rockers but of happy-clappy Christians.

However, thanks to the British art-school system, a generation of rock'n'rollers actually had loftier plans. As the 1960s beat-boom mutated into psychedelia and then prog-rock, the "rock opera" became a familiar ambition for British musicians. Mark Wirtz's A Teenage Opera never really developed far beyond the handful of tracks which in 1967 spawned Keith West's one-off hit "Grocer Jack (Excerpt from A Teenage Opera)", but the same year saw the appearance of the original Nirvana's The Story Of Simon Simopath, the first recorded rock opera.

Its form – the life-story of a damaged individual – would be echoed in the next few years, most successfully in The Who's Tommy, which would go on to be both a Broadway stage production and a film made with Ken Russell's typical restraint and understatement.

Tommy has remained the yardstick by which all subsequent rock operas are measured. It was a form to which Pete Townsend would return constantly throughout his career, first with Quadrophenia, followed in the 1990s by an adaptation of Ted Hughes's The Iron Man, and in 2006 by Wire & Glass.

By the mid-1970s, no British prog-rock band worth their salt didn't have at least one concept album in their catalogue though few scaled the more daunting slopes of the rock opera. Like Townshend, The Kinks' Ray Davies was enraptured by the form, which provided a regular conduit for his fascination with the notion of cultural heritage in projects like Arthur (Or The Decline and Fall of the British Empire), Preservation Acts 1 and 2 and Soap Opera, all of which would be presented in small-scale touring productions.

Perhaps because young audiences were more interested in exploring future possibilities than in preserving the past, The Kinks struggled to make much commercial headway with these projects. That would certainly help explain the disparity between their fortunes and those of David Bowie, whose The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars seemed to teeter on the very cusp of tomorrow, with its mingling of apocalyptic sci-fi, gender confusion, rock'n'roll mythology and mascara. Though never, to my knowledge, actually presented as a large-scale stage production – surely someone is missing a trick here? – the album and ensuing tour would not only hoist Bowie to first-rank superstar status, but provide a foundation-stone for the entire glam-rock subculture.

It was no surprise that of all the prog-rockers, only Pink Floyd managed to stage a rock opera with the requisite sense of scale and ambition, when they brought The Wall to theatres in 1980/81 – though in the aftermath of punk, some observers felt that literally building a wall between band and audience was less a metaphor for the way that societal controls imprison the individual than a literal representation of the gulf that had grown between punters and performers through the 1970s. Undeterred, Roger Waters would employ similarly blunt irony when staging the opera in 1990 at the site of the former Berlin Wall, with guest musicians including Joni Mitchell, Cyndi Lauper, Sinead O'Connor, Bryan Adams, The Scorpions, Van Morrison and The Band.

The Wall represented a sort of rock-opera high-water mark, from which the form ebbed gradually away through the ensuing decades, until Mamma Mia! and We Will Rock You revived its commercial expectations, and Monkey revived its theatrical ambitions. But there was no shortage of putative rock-opera projects in the interim (even if few of them actually made the jump from album to stage). One of the more notable was Randy Newman's Faust, an updated 1995 version, which re-cast Faust as a sulking teenage sociopath, over whose worthless soul the devil (Newman himself) and God (a lordly-voiced James Taylor) dispute with understandable reluctance.

Since then, the jukebox musical has come to dominate theatrical production, with Abba and Queen being joined by Madness (Our House), Rod Stewart (Tonight's The Night), Billy Joel (Movin' Out), Take That (Never Forget), The Bee Gees (Saturday Night Fever), The Beach Boys (Good Vibrations) and even Bob Dylan (the Twyla Tharp-choregraphed The Times They Are A-Changin'). Not all were successful, several productions being panned for the superficiality with which the repertoire was shoe-horned into a narrative. Even The Beatles fell prey to the lure of the jukebox musical with Love, though at least in their case trouble was taken to re-mix their songs specifically to accommodate the nouveau-circus presentation by the Cirque Du Soleil.

The Pet Shop Boys opted instead to write a new musical, Closer To Heaven, centred around the sex and drugs exploits of the denizens of a London gay club. But the pitfalls of failing to capitalise on back-catalogue familiarity became evident when, following an initially successful London opening in 2001, dwindling audiences resulted in the show being cancelled.

Paul Simon suffered a similar fate with The Capeman, his 1998 musical based on the real-life story of a teenage New York gang murderer, Salvador Agron, who in the early 1960s became the youngest person sentenced to death in America, before becoming a born-again Christian, having his sentence commuted to life, educating himself to degree level, and becoming a published poet. Despite the promising subject matter, and the lyrical assistance of poet Derek Walcott, the project foundered, closing after a run of less than three months, at a cost of $11m.

The last few years have seen all the standard rock-operatic strands being continued, with Green Day releasing two "punk-rock operas", American Idiot and 21st Century Breakdown, prog-metal band Mastodon reinventing the Tommy wheel with Crack The Skye, their rock opera about an astral-travelling quadraplegic whose soul somehow ends up in the body of Rasputin. But recent years have also been marked by several other, more significant, attempts to raise the bar of pop's interface with theatre. Commissioned by New York's Metropolitan Opera and Lincoln Center Theater, Rufus Wainwright's Prima Donna is a bona fide opera about a day in the life of an ageing diva preparing for a comeback. Reviews were mixed, critics citing comparisons with Ravel, Massenet, Strauss, Puccini and Mascagni in Wainwright's lush, Romantic score, though some found his orchestrations leaden and repetitive, and the plot was deemed too flimsy.

The nostalgic approach of Prima Donna was perhaps unfairly compared with Damon Albarn's Monkey, which, as the same festival's equivalent keystone work two years previously, drew rapturous praise both for its elaborate, multi-media staging and for Albarn's music, which incorporated Western and Oriental elements and instruments – not to mention a libretto in Mandarin – within a score that was truly original and contemporary. It remains the benchmark for modern theatrical incursions by pop, while Sparks' recently released The Seduction of Ingmar Bergman opens up another possible avenue for serious dramatic involvement by rock musicians: the radio play.

Commissioned by Swedish Public Radio, Sparks' play uses an imagined attempt by American producers to lure the great Swedish director into the Hollywood studio system that he considered anathema to his work, set to a sharply-observed score which draws on influences from jazz, pop and rock to Kurt Weill. This latest musical doesn't require any elaborate staging, relying instead upon the listener's imagination for its mise-en-scène; yet also, unlike most other rock musicals, it possesses a thoughtful, philosophical tone that resonates long after it has finished. Clearly, while theatre as a medium seems ever more reliant upon the rock musical, it appears that the medium of pop can draw on drama without abandoning itself entirely to the theatrical.

'The Seduction Of Ingmar Bergman' by Sparks is out now on vinyl on Lil' Beethoven, CD release follows shortly

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks