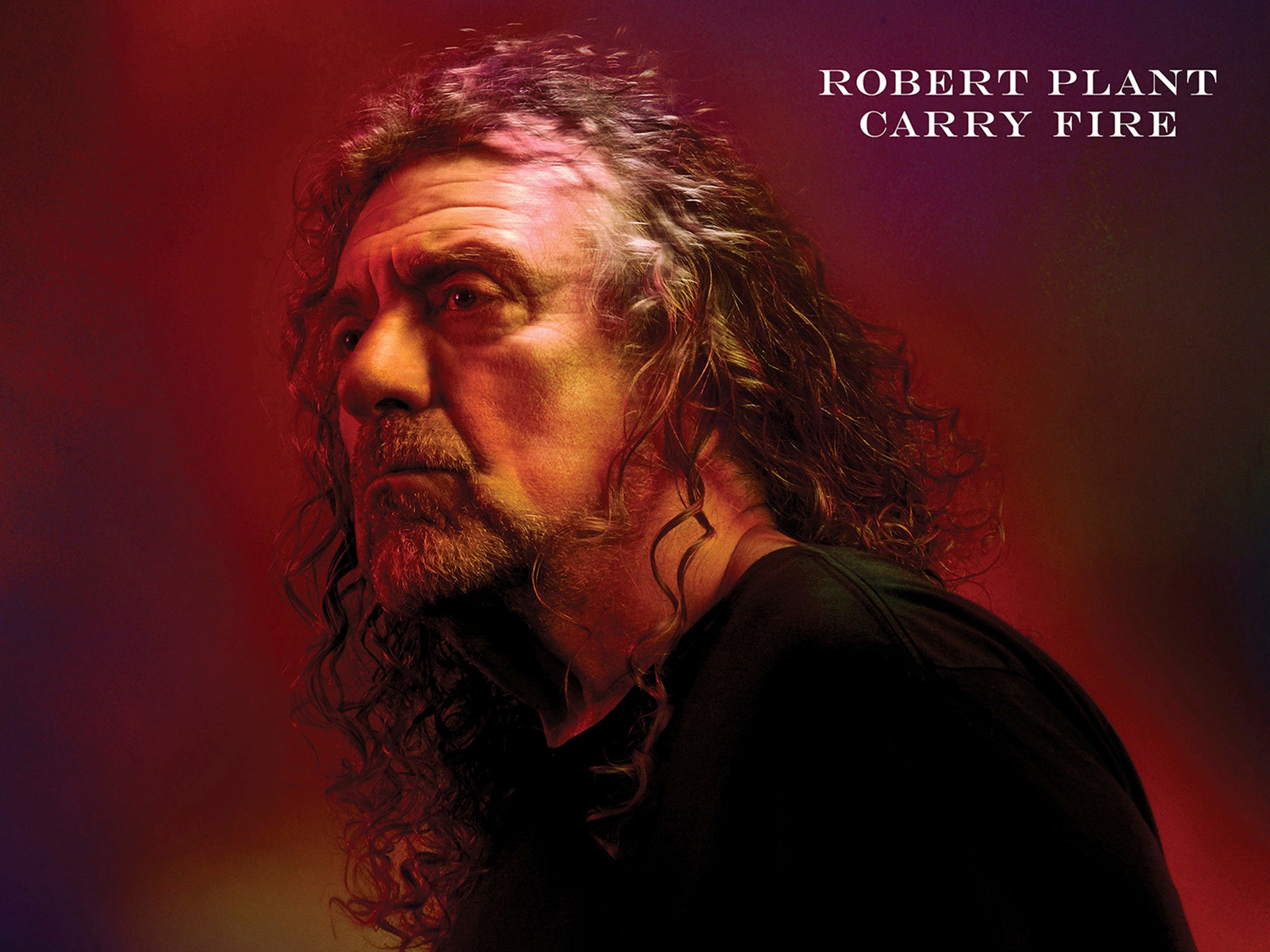

Robert Plant on returning to England, Led Zeppelin and new album Carry Fire

Plant talks to Jonathan Ringen about his inability to deal with attention, working with Alison Krauss and whether a Led Zeppelin revival will ever be on the cards again

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A few years ago, Robert Plant found himself suddenly overcome with an urge to return to his roots. “I know I’m emphatically British,” he says. “But I didn’t realise how much that was true until I’d been away for a while.”

He had been living in Austin, Texas, with his girlfriend at the time, the singer-songwriter Patty Griffin, who was also his bandmate on his 2010 album and tour, Band of Joy. And, for a time, he relished the opportunity to absorb American life and culture. “The hospitality and friendships and initiation into Americana – not just music – was marvellous,” he says.

The process began several years earlier, when he teamed with the bluegrass great Alison Krauss for the Nashville-recorded 2007 album Raising Sand, probably the most acclaimed and successful project of his post-Led Zeppelin career. (He last played with his old band 10 years ago this December, during a one-off gig at the O2 arena in London that made headlines around the world.) The pair won an album of the year Grammy, and the LP went platinum; along the way, he discovered an entire world of Appalachian music and the joys of vocal harmonies, which were never a big part of his musical repertoire.

“It was one of the most rewarding, classic periods of my life,” he says. “And it was just such a...” he pauses to search for the right word, “tear to leave America and return to Britain.”

Plant speaks to me from the lobby of the Frome Memorial Theatre in Somerset, which was built just after the First World War. Since returning from the United States, he has lived, as he put it, “only eight miles from where I learned how to speak French and do geometry” in Shropshire. Affable and chatty, he cheerfully recounts tales from his past lives: as the golden-maned, howling frontman of Led Zeppelin; in partnership with the Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page as Page and Plant; a foray into Eighties synth-rock; and the rootsy solo path he has forged over the last two decades.

On the theatre stage, his band the Sensational Space Shifters – an eclectic crew of British musicians, several of whom he’s worked with on and off since the mid-Noughties – was running through a mix of solo material and reconfigured Led Zeppelin classics. The group was deep in rehearsals for a tour behind Plant’s latest album, Carry Fire: a swirling mix of deep blues, mountain music, North African rhythms and Zeppelin-heavy weight.

“Some people don’t get it,” says Justin Adams, one of the band’s two guitarists, and a specialist in Middle Eastern and African sounds. “Why are you interested in the blues and devotional music from Pakistan? It’s not out of geographical interest, particularly. It’s about transporting music that really takes you somewhere – a beat that makes you feel a slight sense of dread and foreboding.”

In Shropshire, Plant is part of the tapestry, the same way Bruce Springsteen maintains anonymity in his slice of New Jersey. He said his decision to return wasn’t connected to his relationship with Griffin. “It was my own inability to deal with the rabid attention that was paid to me – and there was kind of no way to hide it.”

So he returned to the land of his birth, gathered up the band and got back to work, first with the 2014 album Lullaby and... The Ceaseless Roar, and now with Carry Fire, both of which largely comprise original songs, as opposed to the covers he performed with Krauss and the Band of Joy. With the Sensational Space Shifters, Plant embraces a modern, digital approach distinct from the painstaking analogue perfectionism of Led Zeppelin. Various combinations of the band – which include the keyboard player John Baggott, a veteran of trip-hop acts like Massive Attack and Tricky – split off to write and record interesting chunks of music, which are then woven together in the studio.

“We chop the stuff up and see how it falls into grooves and moods,” Plant says. “That’s basically the whole signature of our music: grooves and moods.” As the tracks cohere into songs, he mines a notebook he’s scribbled in for years for lyrics. “I have a lot of lyrics, and if they’re not interrelated they can be,” he says. The vocal melodies are also all Plant, delivered in a haunting, otherworldly mode. “I tried with this record to make melodies really, really important,” he says.

The result is a heady, autumnal record, blending Plant’s early influences (the folk musicians Bert Jansch and John Fahey), blues-fuelled riffs, Berber sounds and Bristol trip-hop sonics. Many of the songs, including the title track, are love ballads tinged with fables. In contrast, “Carving Up the World Again … A Wall Not a Fence” is a Sun Records-ish stomper spiked with a curling, Middle Eastern guitar solo that delves into post-Brexit and President Trump discourse. Taking part of its title from a quote by Trump, Plant takes aim at jingoism and the refugee crisis. “There’s progress in many areas of humanity, but it’s juxtaposed with doors slamming and pain,” he says.

The sole cover, of an old rockabilly tune called “Bluebirds Over the Mountain” gets new energy from a fractured electronic beat and the twinned vocals of Plant and The Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde.

Plant is delighted that there’s still an audience for his music and a major record label, Nonesuch, invested in releasing it into the world. But that’s about as much thought as he puts into who might be out there listening. He emphatically does not delve into Spotify data to learn more. “No, I don’t give a hoot,” he says. “I couldn’t even think about it. I don’t think I write to suit anybody – I just write to suit my mood.”

As for his old band, Plant said he sees Page and the bassist John Paul Jones “from time to time, and it’s very civil”. The three were thrown back together in 2016 during a high-profile copyright lawsuit over the song “Stairway to Heaven”, which the band won, but Plant doesn’t seem eager to relive that: “We’re enthusiastic toward each other, and each of us does our own things, and that’s how it is.”

When Led Zeppelin ended in 1980, Plant set out to live a more human-scale life. To the public annoyance of his old bandmates, he’s been emphatic about not reviving the band for a full-scale tour, and when asked about it he tends to make an artistic argument about wanting to resist nostalgia. But there might be another, simpler, reason – maybe there just isn’t any payday, no matter how vast, worth more than his carefully cultivated life?

“Yeah, that’s true,” he says. “I know where it’s at for me. I’m in an incredibly good place. For a guy like me, who was a singer in band, who played no instrument – but just being eager to learn and experience more and more music? I’ve just been incredibly fortunate. I’m in the middle of my own joy. I don’t need anything else.”

‘Carry Fire’ is out now

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments