Richard Ashcroft - From urban hymns to united nations

The Verve's Richard Ashcroft is back with a new band, a new name, and a new album. He tells Craig Mclean he's a lucky man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

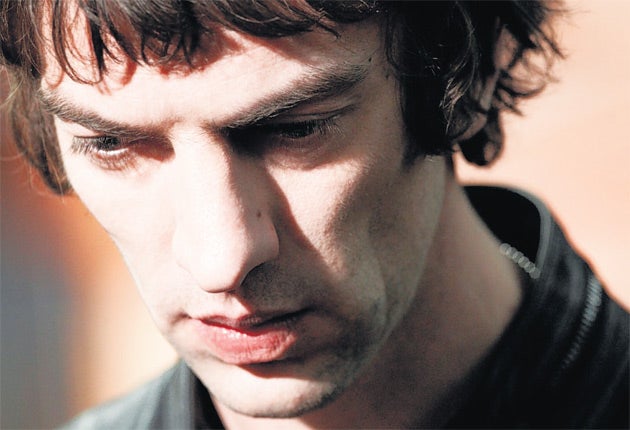

Your support makes all the difference.A hot night in Paris, and Richard Ashcroft was giving the audience what they want, almost. The former singer with The Verve had stalked onstage at Le Trabendo club with his new band, which he has named The United Nations of Sound, and his wife, former Spiritualized keyboard player Kate Radley. All limbs, lips, hips and cheekbones, he'd come to promote his new album, also called United Nations of Sound, a situation somewhat compromised by the fact that the delayed album wouldn't be out for another six weeks.

Ashcroft, the lean, mean, mouth machine about whom Noel Gallagher wrote "Cast No Shadow", had also come fully kitted out as if for a Russian winter rather than a Parisian summer night in a sweatbox club: Gucci overcoat and Belstaff leather jacket, both buttoned up to the neck. Over the ensuing couple of hours the coats would be peeled off and the hits – and the nearly-hits – cranked out. "A Song For The Lovers", 2000's debut solo single, was followed by the baffling revelation that, "I've got a Mexican auntie. She used to sit next to Trotsky." He tried to encourage a little singalong on "This Thing Called Life", a new song no one had yet heard, by telling the French audience that, a couple of nights previously, the Italians had managed to learn the chorus straight away. "I'm not Mr Audience Participation by any means, I've spent 95 per cent of the evening with my eyes closed," he added.

Then he informed the 600-odd people crammed into the club that new track "She Brings Me the Music" was "a beautiful song". To which the only response would be, "he would say that – he wrote it, it's about his missus, and she's sitting three feet away". Finally, when people shouted for "The Drugs Don't Work", The Verve's elegiac No 1 from 1997, he replied, "we'll have to do another night, a request show, six hours long..." After all, he has "too many songs, man, you know what I mean?"

By 11pm it was all over bar the shouting for "Bitter Sweet Symphony". But Richard Ashcroft wouldn't be playing his signature anthem tonight. For one thing, right now he's all about his new gig. He's not even Richard Ashcroft. He's RPA and the United Nations Of Sound. His new musical pals are top-flight American R&B and hip-hop musicians with, variously, work for Timbaland and Mary J Blige on their CVs. He recorded the album in New York with No ID, the Chicago-born producer of Jay-Z and Common.

Ashcroft tells me he didn't want to have a roll-call of big-name guest musicians on the album – he dismisses Damon Albarn's all-star Gorillaz as being a "top trumps" project. Nonetheless, he did try to secure the services of some other American artists.

"Half the people I wanted on the record were either in prison or going there," he avers. "I tried to get Lil Wayne on the end of [new song] 'America', because of his gravel." But the 38-year-old Lancastrian says that the mega-selling rapper was, prior to heading to Rikers Island to complete an eight-month sentence for gun possession, too busy "recording 15 videos and three albums. So, they were in prison, or they wanted 70 grand."

Ashcroft brushes away the suggestion that, after three solo albums of diminishing returns and the disappointment of The Verve's 2008 comeback album Forth, he's rather cravenly "gone hip-hop".

When I look at it, I could have attempted this in the Nineties, 1997, when I was making 'Bitter Sweet'. I could have been working with these guys then, it just took a long time to get there. The idea, if there was any idea, was carrying on this dream of still believing that the roots of music can be drawn on as inspirations. And not mirrored back to you like some facsimile of what you've heard before."

Certainly the album is identifiably something we've heard before: it's Ashcroft in his vaguely messianic, strings-laden, fist-punching, music-is-power default setting, with added beats and groove. But he hasn't sounded this convincing – or indeed sturdily tuneful – since Urban Hymns.

The ghosts of his past are never far behind. He's ambivalent about The Verve's short-lived 2007/8 reunion (actually their second reunion), a comeback that was clouded by rumours of ongoing intra-band argy-bargy. He thinks the always-combustible line-up managed some good gigs, although he claims not to have listened to Forth since then and can only pinpoint three songs that he liked.

"We didn't massacre the past," he offers, a view with which few who saw their stirring Glastonbury headline slot would disagree. "And X amount of people from a generation got to see us who never got to see us before. So, I'm trying to look at the positives now."

Positives around the thorny subject of "Bitter Sweet Symphony" are harder to come by. Yes, The Verve's signature anthem was one of the defining British songs of the Nineties. The first single from third album Urban Hymns, it reached No 2 in summer 1997. It propelled the Wigan five-piece from the post-shoegazey, pre-Britpop doldrums into one of the biggest bands in the country. At the 1998 Brit Awards, Urban Hymns won The Verve the gongs for Best British Group, Best British Album and Best Producer.

Ashcroft proclaims, "it became literally part of the DNA of the country". He considers it both "a gift and a curse if you've been lucky enough to create things that become part of the soundtrack to the times. Which Oasis achieved, and I achieved with The Verve with a few songs. But that's the incredible thing. When it becomes beyond you. You realise you have no control. No real ownership any more. It's not yours any more. That's a great thing."

It is also a pain-in-the-arse thing. Early on in the public life of "Bitter Sweet Symphony", the song was hit by a legal dispute over authorship. In writing the song, Ashcroft used a sample of a version of The Rolling Stones' "The Last Time" by The Andrew Oldham Orchestra. Publishers ABKCO successfully argued that too much of "The Last Time" had been sampled.

Ashcroft had to cede authorship of the song, and all publishing royalties, to ABKCO. "Bitter Sweet Symphony" has subsequently been used in various advertisements worldwide. What does he make of the use of his most famous song on ITV's pre-World Cup international football trailers? "Yeah, that's another of the faked-up ones," he sniffs. "It's not real. They're getting closer and closer so people can't tell any more." He says that this version was played and recorded by other musicians. Why?

"I think it's the easiest way of going about using it... if you're gonna use the original you gotta get my permission. For anything. But if I say 'no', then ABKCO receive money and they allow the company – the car company or whoever it is – just to re-record it. So if they re-record it, that gets me out of the deal."

Judging by his two expensive coats and at least two properties (in one of London's leafier neighbourhoods, and in Gloucestershire), money isn't a huge object for Ashcroft. Still, being cut out of the deal, and therefore out of the fees, must rankle. He insists not. He considers himself the lucky recipient of a greater windfall.

"When I'm sat next to my son [Sonny, 10, big brother to Cassius, six] and we're just about to watch England and he's buzzing that his dad's music is on before the match, you gonna start grumbling about it? My son, he thinks it's great, and you suddenly get [his] naive eyes on it and you lighten up. I mean, it was a door opening. It smashed the doors open massively. It's like anyone who's written big songs..."

Richard Ashcroft has unblinking faith in his own ability to write big songs. He has unblinking faith in himself full-stop. His contrary swagger propels him defiantly onwards – a quality that makes him a "survivor", but also, to many observers, a blow-hard loudmouth. But he denies that this is grade-A arrogance. He traces it back to the death of his dad when he was 11.

"When you lose someone when you're younger the whole time-line of life gets changed completely. It seems to put afterburners on people's lives, whether it's musicians or politicians or whatever. When I look back now to when I was a kid, I was the one who provided a lot of the engine and the energy to the people around me to do something. To get out and do it.

"And I know if you took me out it – and this isn't arrogance, this is just reality – I don't imagine any of the other people involved would have been in a band. I've just got an extra drive," shrugs Richard Paul Ashcroft. "An extra hunger to do something in this short time."

'RPA and The United Nations of Sound' is out on Parlophone

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments