The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Rude Girl Rocks: Meet the 83-year-old reggae matriarch who brought Jamaican music to the world

A documentary and memoir chart the unlikely story of how a former ice cream shop in Kingston came to define Jamaican music. Kevin E G Perry charts talks to the woman at the centre of it all: Miss Pat

When it comes to Jamaican music, Patricia Chin has heard it all. The 83-year-old, known as “Miss Pat”, has been a fixture of the island’s music industry for over 60 years. Today she runs VP Records, the world’s largest reggae music and distribution company, making her a crucial music mogul for the island's music. DJ Kool Herc, who along with his sister Cindy Campbell is considered the founder of hip-hop, once said of the sweet-natured 4ft 11in entrepreneur: “What Berry Gordy was to Motown Records, Patricia Chin is to the reggae industry.”

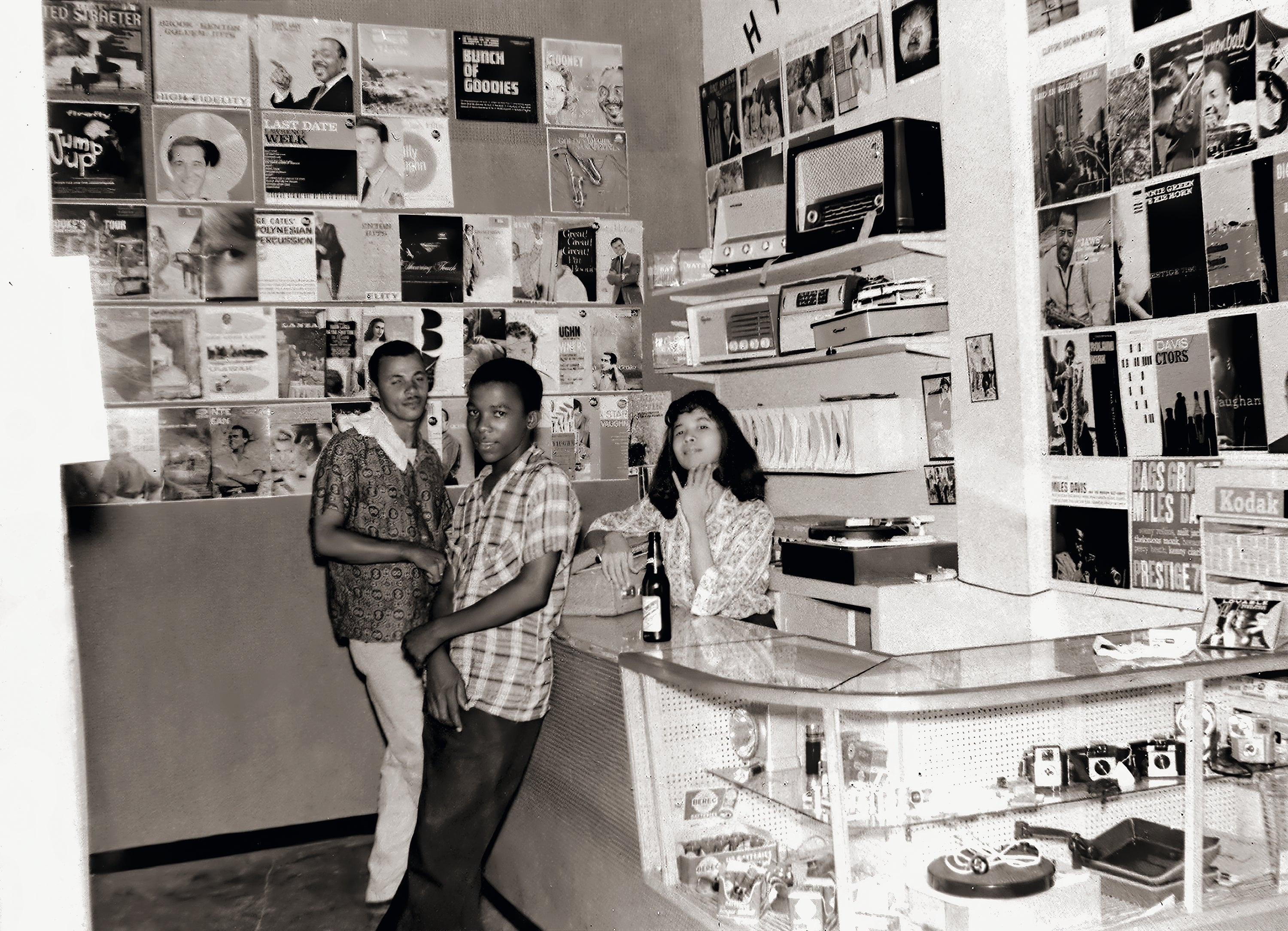

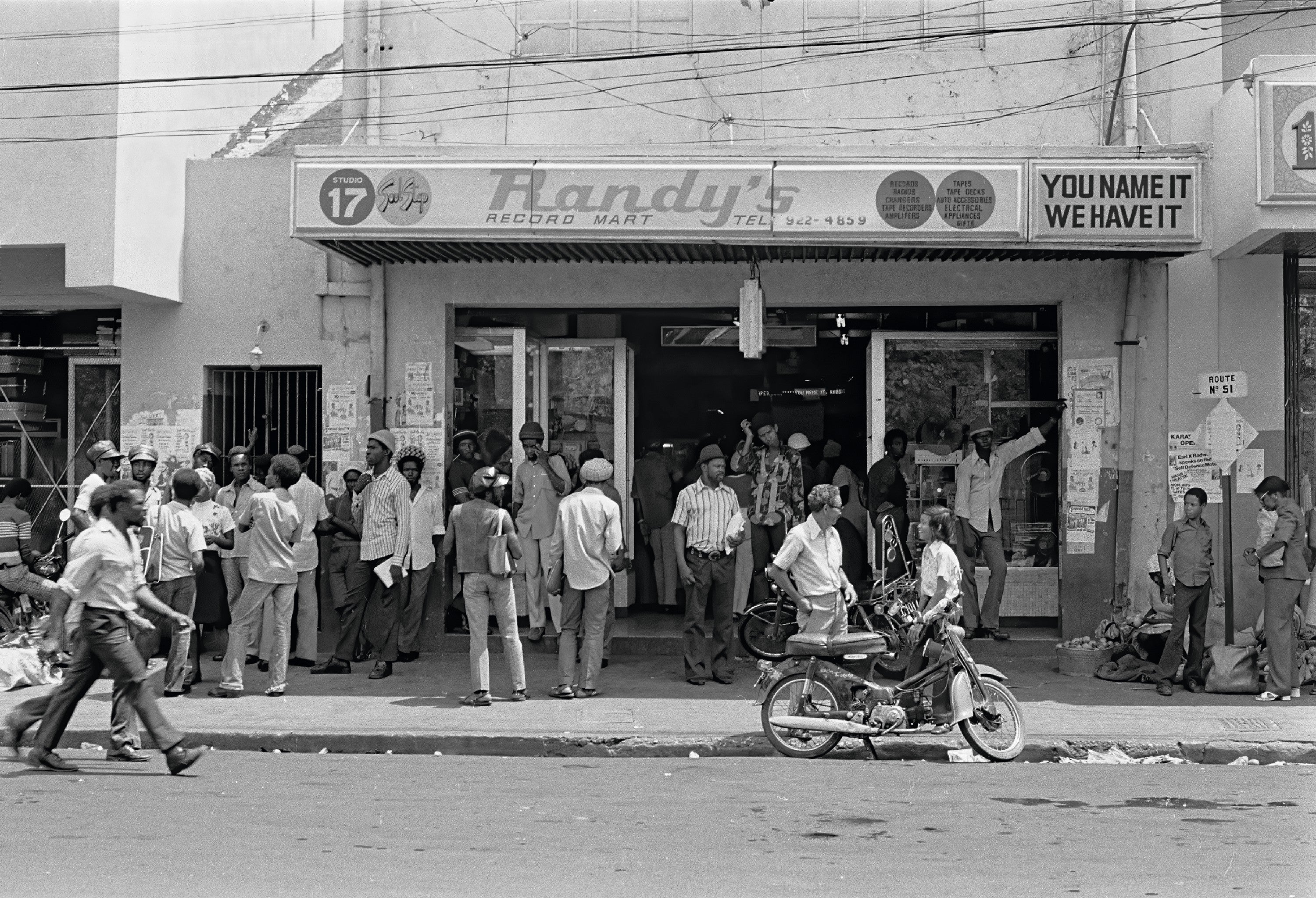

It all started in a former ice cream shop in Kingston, which Miss Pat and her husband Vincent opened as Randy’s Record Mart in 1959. In her new memoir, Miss Pat: My Reggae Music Journey, out this week, she describes how it was there she developed her legendarily encyclopaedic knowledge of ska, rocksteady, reggae, dub and dancehall. It was there, too, that Jamaica’s homegrown musical explosion in the Sixties and Seventies took place, bringing those sounds and styles to the world.

Randy’s, at 17 North Parade, is a central location in the story of Jamaican music. Upstairs was Studio 17, where many classic recordings were made – including a pair of seminal reggae albums produced by Lee “Scratch” Perry for Bob Marley & The Wailers. The studio was so popular that the alley outside became a gathering place for aspiring stars and world-class musicians alike. Known as Idler’s Rest, it was there that drummer Sly Dunbar and bassist Robbie Shakespeare – who would become the prolific reggae rhythm section and production duo Sly & Robbie – met for the very first time.

Miss Pat remembers the atmosphere well. “From 9 o’clock each morning, singers, musicians and record collectors would gather outside,” she says, over the phone from New York. “When they wanted a backup singer, they would just call downstairs and say: ‘Hey, we need a singer! Come up here, Delroy Wilson!’” (Wilson is widely regarded as Jamaica’s first teen star.) “There was a great feeling of community.”

Vincent and Miss Pat’s involvement in the music business started from humble roots. Before the couple opened Randy’s, Vincent Chin had a job servicing jukeboxes in bars across Jamaica and updating them with the latest tunes from the likes of Fats Domino, The Drifters and Sam Cooke. Naturally after each new round of releases, Vincent would be left with a surplus of used records and at his wife’s suggestion, he struck a deal with his employer to sell the old unwanted 45s directly to the public.

Thus “Randy’s” was born, with Vincent lifting the name from a show on a Tennessee-based jazz and country station that he would listen to religiously on ham radio. They soon began to sell new records alongside the old, although their budget was too limited for them to build up much stock. “I used to go and buy one Percy Sledge record, one Jim Reeves record, all the new records in ones,” explains Miss Pat, who was born and raised in Kingston by her Chinese mother and Indian father. “Then we bought one turntable and one needle. Everything we bought in ones. Then we’d sell it and go and buy one more.”

Randy’s slowly grew, one record at a time, and before long, Vincent decided it was time to expand into the recording end of the budding Jamaican music industry. It’s strange to think now that, before the island gained independence from the British Empire on 6 August 1962, if you tuned into a radio station or fed a shilling into a jukebox anywhere in the country, you’d have been unlikely to hear anything but American R&B, gospel and country and western records. Vincent built Studio 17 from scratch in a room above the shop and started experimenting with his own productions.

As Jamaica enthusiastically approached independence, he set about capturing the prevailing mood, recruiting calypso singer Lord Creator (who was actually from Trinidad and Tobago) to record a track called “Independent Jamaica”. It gave the rechristened ‘Randy’ Chin his first hit as a producer.

Studio 17 quickly became a magnet for musicians. Well-known artists like Gregory Isaacs, Dennis Brown, Alton Ellis and The Skatalites all recorded there, yet it was also known as a place that would give a chance to those with few means. “If you were a poor artist and you did a session, you could go downstairs and say: ‘This has just got pressed up, could you sell my record?’” explains journalist Reshma B, who produced the recent documentary Studio 17 - The Lost Reggae Tapes (available now on QwestTV, a new video-on-demand platform founded by Quincy Jones).

“Even if you hadn't recorded at Studio 17, you could sell your records at Randy's. Miss Pat would say: ‘Leave what you have, if we sell it, we sell it. If we don't, you can take it back.’ That didn't happen at other studios.”

The island was experiencing an explosion of musical creativity as the reggae sound began to develop, but only a fraction was making its way onto the radio, which at the time rarely played anything other than American records. To get around this, many producers had their own sound systems, rigged to huge speakers and set up on the back of trucks for street parties where they’d compete against others to play the best tunes. Miss Pat was a fan. “I wasn't a good dancer, but I was a very good listener,” she says. “I knew all the versions.”

Working behind the counter at Randy’s, Miss Pat had learned the ability to identify everything they sold by ear alone. In her book, she recalls a day when her skills were put to good use by sound system selector Tony Screw, known as Downbeat The Ruler, who came in looking for a particular remix of a record. The only problem was he had no idea what it was called or who it was by. Miss Pat told him to hum it for her.

“I was really versed,” she says. “Because I stayed so long on the counter, I listened to every record – good, bad and indifferent. When I found the record for him, he was so overjoyed. He said: ‘Miss Pat, please, if anybody else wants this record, tell him you don’t know it!’ He wanted to play it against another sound system. He still reminds me of that. He says: ‘You made my day, you made me win that contest!’”

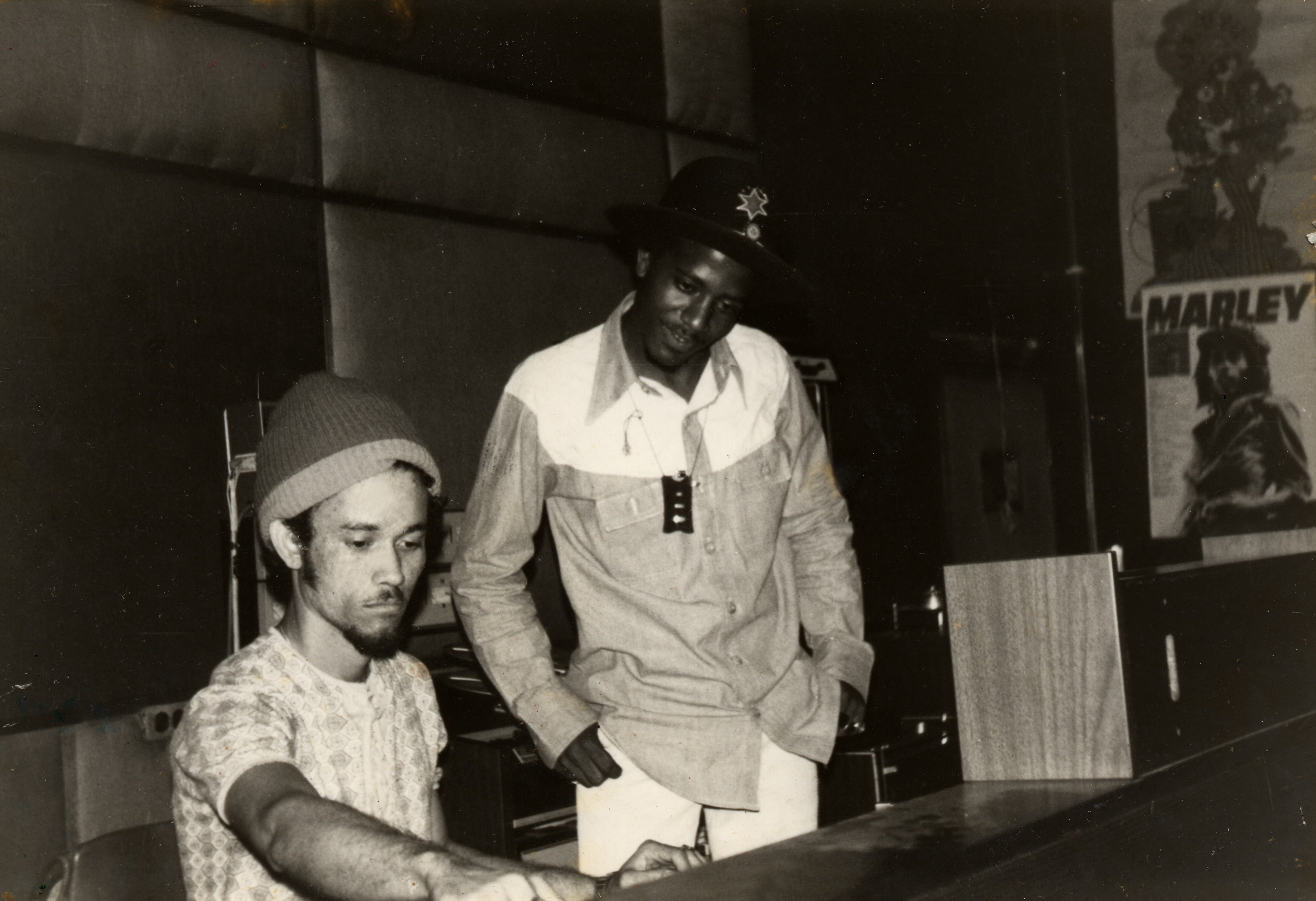

The reputation of Studio 17 was such that it was where The Wailers, the band central to reggae’s global reputation, laid down their first reggae music. In August 1970, Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer approached maverick producer Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry – who would go on to become a pioneer of dub music – about producing their second album and helping them to move away from their earlier ska sound. For Perry, there was only one place he wanted to use to record their first full reggae album.

Clive Chin, Vincent’s son from a prior relationship, was 16 when Perry recorded the Wailers at Studio 17. Then a budding record producer, he says he learned a lot from watching Perry turning up at the studio laden down with pots and pans to use in his recordings. “People call him a madman, but Scratch is a very innovative producer,” says Clive, now 66. “I found out that you can use just about anything and put it in the music.”

To illustrate his point, Clive gives the example of one of his own productions: Alton Ellis’s cover of Cornelius Brothers & Sister Rose's “Too Late to Turn Back Now”. “Listen to the rhythm guitar,” he instructs. “That’s not a Fender Strat. That’s actually a cheese grater.” He explains that instead of using a guitar to get the specific sound he wanted, he recorded the sound of a fork being scraped over the grater holes. “It makes a very nice sound, very crisp,” he says. “You have to be creative.”

It’s perhaps no surprise that, having grown up surrounded by the milieu of Randy’s, Studio 17 and Idler’s Rest, Clive Chin became a revolutionary producer in his own right and has worked with anyone who’s anyone in reggae. “Java”, a track Clive produced for his school friend Augustus Pablo, gave him his first hit and is considered one of the earliest examples of dub-reggae.

The album they made together, This Is Augustus Pablo, remains a classic of the genre and a prime example of Clive’s musical innovation. “I found instruments so fascinating,” he says. “There’s a track on that album called “Please Sunrise”. The lead instrument was an acoustic piano, but then I had Pablo put in a melodica harmony. I found it was so embracing. It enhanced the track.”

The Chin family left Jamaica in the late 1970s as the country was engulfed in political turmoil. They left in such a hurry that Studio 17 was left behind to fall into disrepair - and it was only decades later, during the filming of Studio 17 - The Lost Reggae Tapes, that Clive returned to salvage master tapes that had been left there. After relocating to New York, Vincent and Pat established VP Records (named after their initials), now the world’s largest independent distributor of reggae and dancehall music, which has discovered and nurtured stars including Sean Paul, Maxi Priest, Lady Saw and Beenie Man.

Miss Pat remains at the helm – and retains that vast and enviable music catalogue in her mind. There’s a special place, of course, for “Independent Jamaica” and the other early recording produced by her husband, Vincent “Randy” Chin. “In those days, we were naive,” recalls Miss Pat. “We were just doing music out of pure joy because we didn’t have a culture called Jamaican music. It was all American music. We were just experimenting. We were so naive, but it was fun. It was pure fun.”

Miss Pat’s autobiography My Reggae Music Journey is out now from Gingko Press. Studio 17 - The Lost Reggae Tapes is available to watch on Qwest TV.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks