Randy Newman’s scathing satire of America is his life’s work – and never more relevant than now

Over a 60-year career, the singer-songwriter and ‘Toy Story’ composer has chronicled America with a sharp eye and unrivalled wit. Zoë Beaty talks to the writer who has delved into ‘the insecurities, the depressions and the difficulties’ on his creative journey

In 1968, in a studio in California, one of the great political satirists sat down at the piano and began to sing. This was his first album; his tunes were an ode to deep suburban blues, while his lyrics told stories of life in America. They spoke of romance, of the nature of the conventional family; the oppression of the old, the fat, and other outcasts in society. In later years, his clear-eyed wit would be applied to racism, religion, Ivanka Trump, apartheid, George W Bush, economic disparity, the hypocrisy of the white middle class, the environment and homophobia. But you might know him as the Toy Story guy.

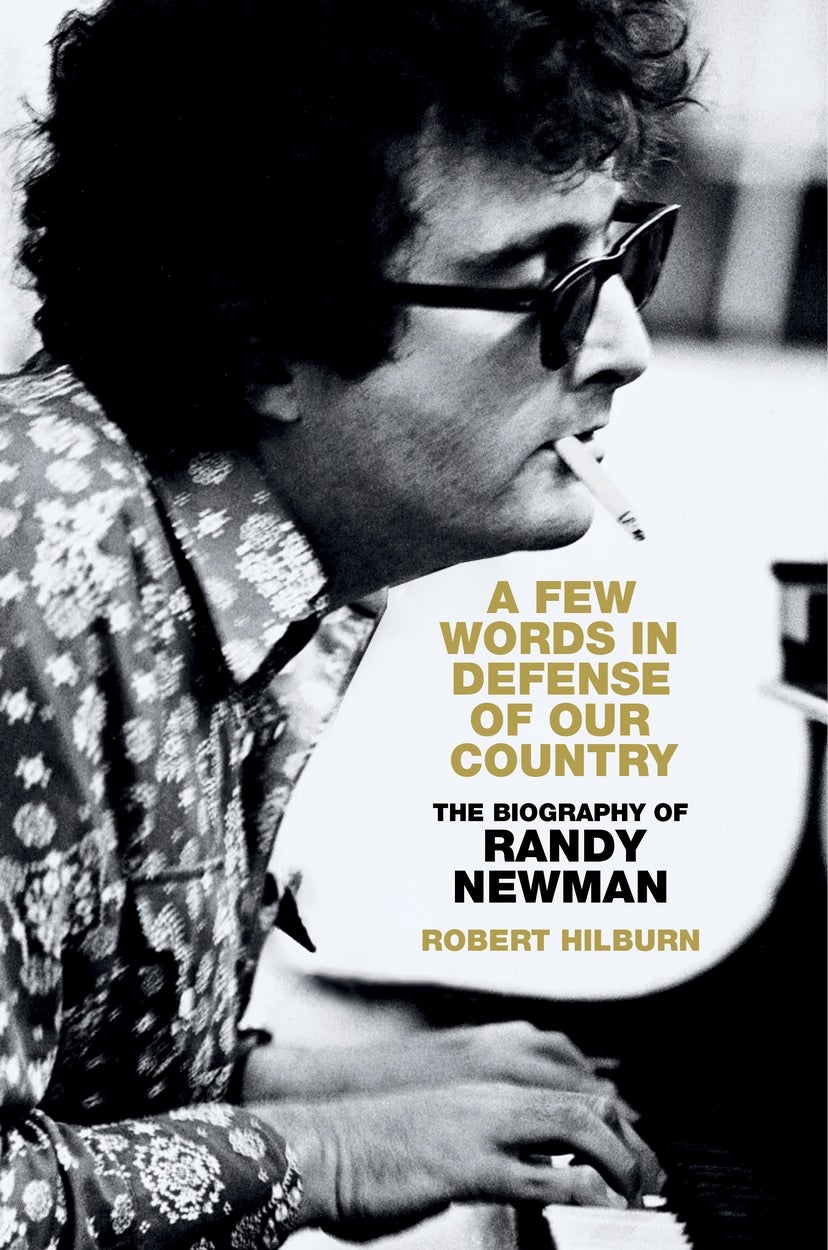

Long before Randy Newman, 81 today, won global acclaim for his unforgettable score on the original 1995 Toy Story movie, his unconventional, intellectual – and darkly comic – writing presented a remarkable commentary on the state of America. Over almost 60 years, the seven-time Grammy Award-winning writer, pianist, composer, and arranger has established himself as one of the most revered songwriters in history. In a recently released book, A Few Words in Defense of Our Country: The Biography of Randy Newman, former Los Angeles Times pop critic Robert Hilburn leaves no room for doubt.

Hilburn first met Newman in 1970, when he attended his debut at the iconic Troubadour club in West Hollywood, a venue that was instrumental in launching the careers of countless Sixties and Seventies stars including Elton John, The Byrds, Carole King, Bonnie Raitt and Tom Waits. The pair would go on to form a connection that has spanned decades. But Hilburn wasn’t immediately blown away. “Here was this guy,” he says, “there was no guitar, there’s no band. There’s just him at the piano, and he sings in this weird Fats Domino voice. I thought, well, where does this person fit into the pop scene? Who is he trying to follow?

“I reviewed him and I didn’t say he was going to be a big star,” Hilburn admits. “I said he was going to be a creative master.”

Among his peers, he is the star. Bob Dylan, who was captivated by Newman’s “I Think It’s Going to Rain Today” – which appears on his eponymous debut album, released in 1968, and was subsequently covered by the likes of Nina Simone, Dusty Springfield, Joe Cocker, and many more – gives testimony to the “sadness and cynicism” of Newman’s rendition in Hilburn’s biography. “It’s a strange combination, but Randy always manages to pull it off,” he adds. Likewise, Newman earned the respect of Etta James, who recorded an electrifying cover of one of his greatest, “God’s Song (That’s Why I Love Mankind)”, as well as Paul Simon and Bruce Springsteen – for songwriters, it doesn’t get much better than Newman.

And yet – despite covers of songs such as “You Can Leave Your Hat On” and “Mama Told Me Not to Come” becoming classic pop – Newman never really found commercial success to the same degree as his peers. “He never became a huge seller,” Hilburn explains. “He was frustrated with it, but there was a reason for it.” While popular songs like “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” came easy – “probably overnight”, says Hilburn – the writing didn’t hold Newman’s attention.

What did interest him was getting under people’s skin. Newman’s sharp eye and palpable wit made him an accomplished satirist, and, says Hilburn, “he knew where to point the camera and take aim. He was always looking to write about the underdog,” he adds, “about shortcomings in the American character, serious issues.” Even some of Newman’s livelier songs are not what they seem – like “I Love LA”, a seemingly jolly valentine to his hometown, which, upon closer inspection, is a tongue-in-cheek take on its vapid heart – or “aggressive ignorance”, as Newman later called it.

“He’s written more about America’s problems and cultural shortcomings than any other songwriter – more than Dylan. Even now, no one is looking at these problems as significantly as Randy. He’s been doing it for 50 years. And much of what he saw is still playing out today.”

His Pixar fables – he’s written countless award-winning soundtracks, including for Cars, Monsters Inc and A Bug’s Life – imagine a world beyond reality, but Newman’s best work and most valuable skill turns the world inwards. He’s a master of storytelling, expertly harnessing the power of simplicity in introspective ballads, and stylistically he’s mighty – baked in New Orleans rhythm and blues, and heavily influenced by Fats Domino and Ray Charles, among others. In his vast back-catalogue, he comes alive writing biting satire that is cleverly confronting. Cutting, and cuttingly humorous observations on sociopolitical chasms – between the rich and the poor, in power and discrimination – are not just a commentary, but an invitation to consider the roots of our own beliefs and prejudices.

Newman’s critically acclaimed 1974 album Good Old Boys, his fourth studio release, is the archetype here. It was originally envisioned as a storybook of the life of an imagined man – Johnny Cutler, “an everyman of the Deep South” – but was later adapted as a tour of Dixieland, as told by a series of characters.

In between weird and wonderful stories, his typically clear-cut observations on institutional racism, bigotry and class discrimination play out loud, track after track. “Guilty” hears the inner world of an addict (”You know, I just can’t stand myself/ And it takes a whole lot of medicine/ For me to pretend that I’m somebody else”). In “Kingfish” and “Louisiana 1927”, which tells the story of the Great Mississippi Flood, in which more than 200,000 Black Americans were displaced from their homes, Newman laments that “They’re tryin’ to wash us away”, documenting the widespread political apathy and abandonment of Black communities in the aftermath of the deadly disaster. When history repeated itself after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the song became a modern folk anthem among rebuilding communities.

Musically, Good Old Boys is quintessentially Newman – cinematic, orchestral, emotional, anchored by Americana blues and his signature Southern-accented vocals – but it’s not always easy to listen to. Hearing the n-word, which is repeated eight times, is excruciating. As Hilburn says, this was Newman taking aim and pulling the trigger: the voice that Newman inhabits to narrate the album’s lead track, “Rednecks”, is not his own, but that of a casually racist Southerner.

In the song, he targets not only white supremacy in America’s Deep South – the character defends Lester Maddox, a racist, segregationist chicken-shop owner turned unlikely 1967 governor of Georgia, recently dubbed “the original Donald Trump” – but also the hypocrisy of the white north. There, sings the “redneck” – a derogatory slur against the white, Southern working class – Black people are “free to be put in a cage/ In Harlem in New York City”. Even 20 years after its release in 1995, Newman admitted that, quite rightly, he would be nervous to perform it.

It’s not Newman’s most controversial release, however – that title belongs to “Short People”, described by Hilburn as “a silly, stupid song that was popular”. On the off-chance you haven’t heard it, the song, from his 1977 album Little Criminals, declares that “Short people have no reason to live” – over and over again. It became a novelty. But it also provoked long-lasting controversy, and even death threats. “Randy doesn’t like to reveal himself so much but, because he wrote a lot of satire about prejudice, people assume it’s another big statement. But actually, it’s not. It’s just a funny song.”

He called it torture. He always had to find what was important enough to say; he really wanted to truly explain his country. Sometimes, for one song, he’d read a 500-page book to learn about [the subject]

Newman isn’t in the habit of talking about his songs, or his successes, Hilburn says. In fact, he’s always described himself as quite shy, and introverted. Born to non-observant Jewish parents, he grew up between LA and New Orleans (which explains those Southern inflections), occasionally experiencing anti-semitism but mostly questioning why he should be comfortable in his own skin while others couldn’t. “I asked my mom why the Black kids weren’t getting an ice cream from the same side of the ice cream truck I was getting mine,” he once recalled to the Houston Chronicle.

Over time, growing up in an intensely musical family – today, the Newmans have the most Academy Award nominations between them of any extended family, with 92 in various musical categories – stirred up a sense of imposter syndrome that stuck around for much of his career. “From his family, I think he learnt perfectionism and insecurity,” Hilburn explains. “So you can imagine that you’re so insecure you’re doing this, but it’s got to be perfect. He called it torture. He always had to find what was important enough to say; he really wanted to truly explain his country. Sometimes, for one song, he’d read a 500-page book to learn about [the subject].”

Nowadays he spends most of his time in his “den” at the family home in LA, “where he watches a lot of TV”, Hilburn says. It’s where most of their interviews took place. It took a long time for Hilburn to convince Newman that the biography was a good idea – he was initially uncomfortable talking about family, or his personal life. “In fact, as I tried to probe a little deeper, he got angry a couple of times,” he explains. It wasn’t until the author spent time interviewing Newman’s children – he has five, including Eric Newman, showrunner of Netflix hit Narcos – that a deeper understanding of the star emerged.

“I found everything that Randy didn’t tell me, about the insecurities, the depressions, the difficulties in his life – the joys in his life, but mainly the struggles.

“He’s not a real happy person,” he says. “Most of the time, psychologically, he tried to stay in the middle ground – not really happy, but not unhappy either. Which is probably why he spends so much time watching television, rather than going out in the world.”

It’s been seven years since Newman last released an album, Dark Matter, which was ranked the sixth-best album of the 2010s by veteran music critic Robert Christgau. True to form, it’s a polemic, showcasing Newman’s views on the future of the planet, ageing, and loss, and is packed with as much humour as dense discourse.

Released 49 years after his first record, it contains one song in which Vladimir Putin is the butt of the joke. Newman sarcastically attacks the Russian president’s try-hard macho image. “All those pictures were appearing of him with his shirt off, and I couldn’t understand why,” Newman explained at the time. “What did he want?” The track – which he later admitted he had to tone down from its much harsher original – won him his seventh Grammy for Best Arrangement, Instrumentals and Vocals.

One man had a lucky escape from Dark Matter: in the same year, Newman also wrote a (very silly) ditty about US president-elect Donald Trump, in which he compared the relative size of their penises. The finely tuned lyric of the chorus – the only one – went simply, “What a dick!” Newman made the unlikely decision to leave it off the album. “I just didn’t want to add to the problem of how ugly the conversation we’re all having is,” he told Vulture in 2017. Perhaps this is one of his biggest statements of all: in Randy Newman’s modern America, even satire won’t do.

‘A Few Words in Defense of Our Country: The Biography of Randy Newman’ by Robert Hilman is out now in hardback, eBook and Audio (£25, Constable)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks