Death used to be the end of rock stars – now it’s an opportunity to cash in

From Lil Peep to Leonard Cohen, labels have realised that death massively enhances a musician’s bankability, writes Ed Power

It’s a big month for some of our favourite departed artists. A new Leonard Cohen album will saunter into the world on Friday, the same day that Seventies soft-rock troubadour Harry Nilsson attempts a comeback 25 years after his death.

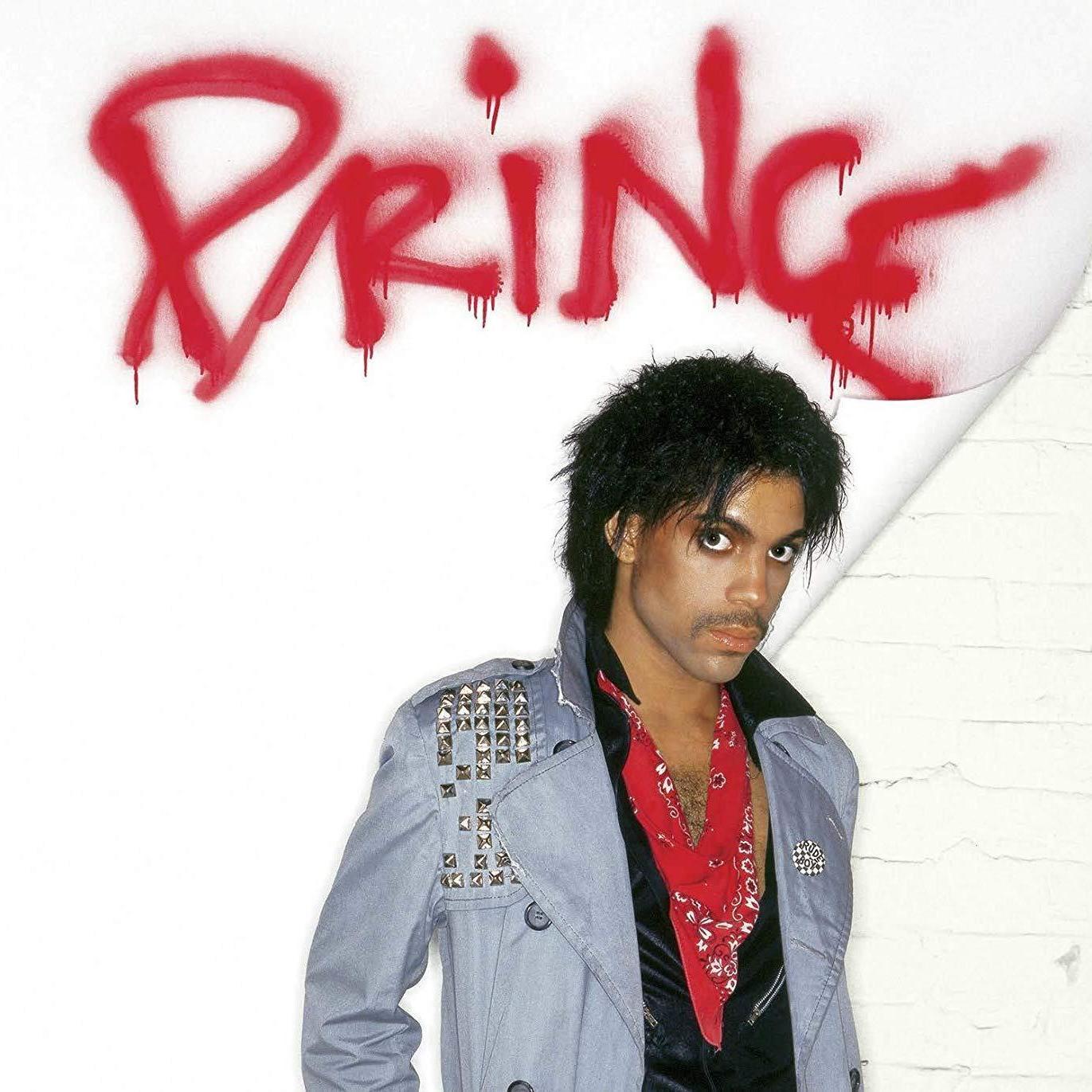

This follows the arrival of a collection of previously unreleased tracks by Long Island “emo rapper” Lil Peep, who died in 2017, titled Everybody’s Everything (accompanied by a tie-in documentary of the same name). Never one to be eclipsed, funk aristocrat Prince has just surprised fans from beyond the grave with a new 7-inch single that captures him at his sultry prime. If the acoustic recording of “I Feel For You”, laid down originally in 1979, was any steamier it might well be an indictable offence to listen to it in public.

So this Avengers-esque assembly of balladeers, crooners, rhymers and funkateers have clearly been staying busy. Or at least, their estates have.

The fact that all the aforementioned performers are dead hasn’t done much to dampen public enthusiasm. The new Cohen record, Thanks for the Dance, is one of his most anticipated in decades, furnished as it is with starry cameos by Beck, Feist and Damien Rice.

Lil Peep’s latest release has, in much the same fashion, been accompanied by a level of media attention the artist born Gustav Elijah Ahr could only have dreamed of prior to his fatal drug overdose aboard a tour bus two years ago. Prince’s single will be followed by an expanded edition of his landmark LP, 1999, featuring 35 previously unheard tracks. As with the two previous “new” Prince LPs to drop since his passing, it will be released by Warner Bros. The singer feuded bitterly with the label in the Nineties, but his estate has now reached an entente with them. A tie-in 1999 podcast has just been announced, as Prince would have wished.

Of course, posthumous records aren’t an entirely new phenomenon. Nobody today thinks of Otis Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” as a galling cash-in, though it was released a year after his death in a plane crash in December 1967. Nor were accusations of poor taste directed at Joy Division when their masterpiece, 1980’s Closer, reached record stores two months after the suicide of Ian Curtis (though the tomb-depicting cover image caused eyebrows to drift upwards).

The difference is that this material had been completed and was ready to be shared with the world. No mausoleum gates were crowbarred open. Nobody was being disturbed from their final rest. All of that changed, from the Nineties onwards, as labels realised that death massively enhanced a rock star’s bankability. Epitomising the trend were the two great lost icons of the decade. Tupac Shakur and Jeff Buckley. Each was to become a ghoulish lab-rat for posthumous careers in music.

Tupac had four studio LPs to his name when he was shot dead in September 1996 in an escalation of the era’s notorious West Coast vs East Coast rap feud. His work rate actually increased after he died, with six full-length official albums to follow. The fifth of these, 2004’s Loyal to the Game was produced by Eminem and featured the late rapper’s vocals doctored so that he appeared to be saying “Drop That Beat, Em!” It’s what Tupac would have wanted. Said no one ever.

Buckley’s fate was not quite so macabre. It is is nonetheless illustrative. While recording his debut album, Grace, he had been clear about wanting to set to one side the track “Forget Her”, deeming it not up to scratch. After he drowned in the Mississippi river in 1997 at the age of 30, a new edition of the record was issued…with “Forget Her” cheekily bunged on. A second “album” of hazy semi-realised songs, Sketches for My Sweetheart the Drunk, followed in 1998.

These were demos Buckley had never intended to share with the world, yet here they were all the same. Buckley’s legacy was ever so slightly blotted. Still, the record went top 10 in the UK – vindication, from a commercial perspective, for having cobbled it together. If this was sacrilege, though, it was simply one among many, as rock stars were summoned en masse from beyond the grave. The Beatles had, a few years previously, put out Free As A Bird, an uncompleted John Lennon demo from 1977 which now received the full Macca kitchen-sink studio treatment. The Fabs had laid Lennon’s memory out on a slab and then garlanded it with their own accoutrements.

With the success of these records – Shakur’s especially – death was suddenly seen as an opportunity, instead of a full stop. True, Amy Winehouse’s unfinished demos were destroyed in 2015 to prevent her record label “doing a Tupac” on her. “It was a moral thing,” said Universal Music chief executive David Joseph. “Taking a stem or a vocal is not something that would ever happen on my watch. It now can’t happen on anyone else’s.”

But did his dramatic intervention come too late? There had, after all, already been a posthumous Winehouse release, 2011’s Lioness: Hidden Treasures. “This isn’t a Tupac situation,” producer Salaam Remi had said, getting his defence in early. Fans wading through Winehouse’s watery cover of “The Girl from Ipanema” and a scratchy demo of “Valerie” may have felt differently.

And that was nothing compared to the wrecking ball taken to the reputation of the late rapper Christopher Wallace, aka the Notorious BIG. In 2017, “Biggie” was required to “duet” from beyond the grave with his wife, Faith Evans, on remix project The King And I.

Of the many affronts to music, taste and basic human decency contained within, surely the most egregious is that visited upon “Ten Crack Commandments”. The song originated as a beginner’s guide to selling freebase cocaine in Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill projects. Here, reconfigured as “Ten Wife Commandments”, it is styled as a road map to a happy marriage. A bad-boy rapper was resurrected as a relationship counsellor.

Similar humiliations were heaped upon Johnny Cash with 2009’s Johnny Cash Remixed. The song “Get Rhythm” is retrofitted with a thumping house beat, while “I Walk the Line” includes a rap verse from Snoop Dogg that, as far as recollection serves, did not feature in the 1956 original. Understandably, Cash’s fans were less than chuffed.

If 21st-century pop can claim a Tupac of its own, it is surely the late Jahseh Onfroy, aka rapper XXXTentacion. He was a mildly notorious Soundcloud artist with a history of domestic violence when he visited a motorcycle dealership in his native Miami in June 2018. Shot dead trying to exit the premises, he was immediately elevated to musical martyrdom.

Skins, his inaugural posthumous LP, topped the Billboard charts last Christmas. It is expected that the feat will be repeated with upcoming follow-up Bad Vibes Forever, Vol 1. This was actually the first record Onfroy recorded, and has languished in the vault for three years. Would it have ever seen daylight had he not been gunned down?

Still, not all posthumous records are created equally. The Cranberries were explicit about wishing to honour the memory of late frontwoman Dolores O’Riordan when they finished the album they had begun together prior to her death in January 2018. And they did so only after receiving the approval of her family.

“The first couple of days it was very odd and very emotional,” drummer Fergal Lawler told me last April. “We were all thinking… ‘Are we going to be able to do this?’ We tried to knuckle down and focus on the job at hand. Dolores didn’t like singing during the day, because she wanted her voice to warm up. So during those times, you kind of forgot about it. But then the evening would come around and it would hit you again.”

The new Cohen album, meanwhile, was overseen by the singer’s son Adam. He was acting on the wishes of his father who had asked that sketches recorded during the making of 2016’s You Want It Darker be brought to fruition.

Cohen doesn’t need the publicity. But sometimes new music from an artist long passed can keep their name alive. That is the case with blues guitarist Rory Gallagher, whose reputation has grown since his death in 1995, largely due to a steady stream of new material, most recently a collection of previously unheard blues recordings issued last May.

Such releases, says his brother Donal, are "important in keeping Rory's legacy alive". Donal continues to oversee releases from Gallagher's archive. "I always bear in mind the fact that this may be the listener’s introduction to Rory and for existing admirers that the experience is somehow refreshing,” he says. "There is a duty, I feel, to only release material that meets a standard that Rory himself would’ve been happy with and that shines a light on his craft.”

Similar motivations would seem to inform the new Lil Peep album. For producers Brenden Murray (aka Bighead) and Ben Friars-Funkhouser (Fish Narc), the record is a way of saying goodbye to an artist with whom they worked extensively and intimately prior to his death. Now that it’s done, to those involved, it finally feels as though their friend is gone forever.

“In a weird way, as long as we were working on it, and as long as it wasn’t it, my work with him was still kind of in this beautiful limbo where it wasn’t really done,” said Friars-Funkhouser, outlining to Rolling Stone the process of assembling the LP. “It’s a little sad for it to be done.”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks