Pills, thrills and bellyaches: Glastonbury ain't what it used to be

Through hazy memory, drug-fuelled recollections and names changed to protect the guilty, our anonymous veteran of the 1990s Worthy Farm campaigns reminisces over the days when you could pick up a ticket in a nearby cafe on the day of the festival – and it wouldn’t set you back £240

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s Glastonbury o’clock. Do you know where your children are?

In the field of dreams of course, charging their iPhones from electricity generated by a clown on an exercise bike, watching the sun glint off the silver’d roofs of the glampers’ Winnebagos, getting down the front early for Ed Sheeran, sitting on the grass digging a wooden fork into a tray of falafel, looking fabulous in Hunter wellies and denim shorts, aching for a retweet or a millisecond of airtime on the teatime news. What memories they will make!

Maybe. Maybe they are indeed embracing the superficiality of Glastonbury, sipping the froth from the craft beer in the pop-up micro-brewery, licking the hundreds and thousands from the Fab lolly, enjoying the sheen of travelling media circus in search of the beautiful people. Maybe that’s all there is in these days of £240 tickets sold by lottery which are snapped up quicker than it takes to say “New Fast Automatic Daffodils” three times.

That was never my Glastonbury. It was there, of course, I’m sure, or aspects of it were. I saw these people who went just for the music and the bonhomie. I moved among them like a ghost. Or perhaps that should be the other way round. They moved among us like bright sprites, because it always seemed there were more of us than them. We, the night people.

And it’s always night at Glastonbury, even in the blazing sun. The best night out you’ve ever had, from early in the morning until early the next morning, rinse and repeat, fuelled by pills and thrills and bellyaches. When night-time proper rolls down the vale of Avalon like a sea-fret, you’re barely aware that the field of dreams has been cloaked in darkness, because darkness, of a sort, has already been served up for breakfast, dinner and tea.

What follows is not to be trusted, other than the fact it all happened, more or less. Don’t ask for dates and times, because in the field of dreams watches are useless; time becomes a loop. All I can say for sure is that everything happened sometime in the 1990s.

To Worthy Farm, where we set our scene. There is me, there is K, who is my constant companion throughout. There are others who move in and out of the decade-long, stitched-together Glastonbury narrative: J, T, P. I can’t be sure, but I think our first one was 1992, by dint of the fact that crusty rockers The Levellers were shouting about freedom. K and I had bought tickets – less than the cost of a parking pass this year. P walked into a cafe in Glastonbury town and bought one over the counter. Imagine! J headed off into the fields where a gang of scallies had ripped a hole in the fence and were letting people through for a fiver.

There always seemed to be a gang of scallies offering services for a fiver. Hooky Back To The Planet T-shirt for a fiver. Unwieldy rolled poster of Ozric Tentacles for a fiver. Slit your throat for a fiver.

That first Glastonbury there was a blue sky, green grass, something agreeable and distant on the second stage. We lay in the grass and watched a far-off balloon floating high in the sky. One of us pointed at the dot and said, “Someone’s fallen off the world.” We all entwined our fingers in the grass, and held on, for fear of falling off the world as well.

That was the drugs, of course. It was always the drugs. So many drugs. All those first arrivals at Glastonbury seem to me now like stepping into a warped version of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, purveyors of fine illegal narcotics lining up to offer their wares. It wasn’t big and it wasn’t clever, but it was Glastonbury. Don’t try this at home. No, really, don’t try this at home.

I remember watching, entranced, as a young man bursting with entrepreneurial joy stood by the path and called out relentlessly like a melodious songbird, “Weed! Speed! Guaranteed!”

I remember a beaming Welshman called John – probably not his real name – who, on the one year that we bothered with a tent, rocked up as soon as we’d arrived, dressed in a shabby suit and carrying a briefcase. “What you lads after?” he inquired politely. Well, what have you got, Welsh John? He opened the briefcase. He’d got the lot.

I remember that even in this counter-cultural Eden it was still a case of caveat emptor. Depositing two white pills in K’s hand, some seemingly trustworthy stranger winked and said, “Take care, lads, that’s strong stuff.” An hour later we looked at each other. “That was just a coffee sweetener, right?”

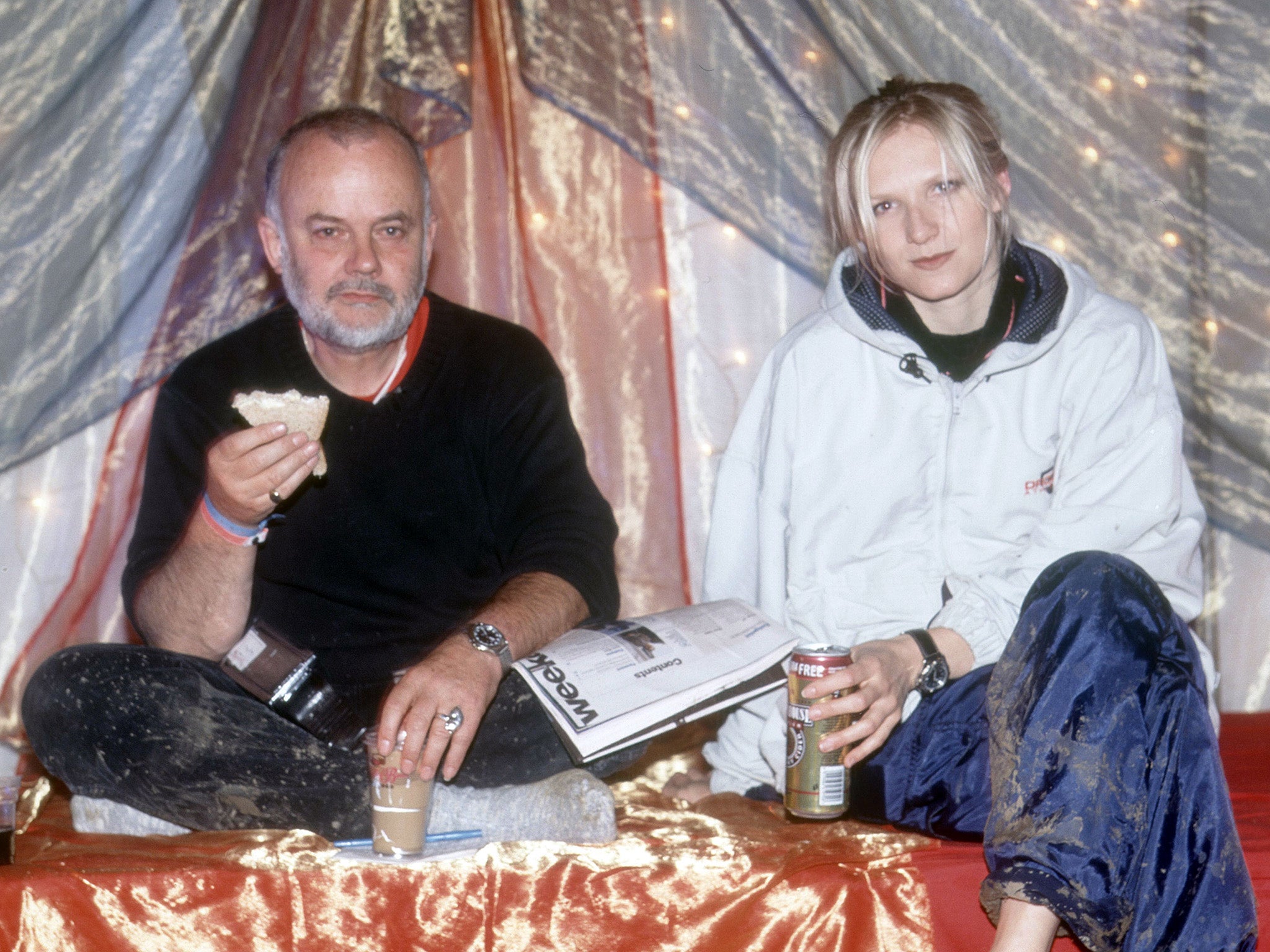

But more often than not the drugs did work, and they pulled back the veil on Glastonbury, offered passage to the unseen world behind the set dressing. Enter freely, and of your own will. One year which I feel must have been 1994, was notable for several reasons. Number one, we saw John Peel in the crowd. Number two, we bought a batch of really duff acid. We sat in our car, sulking, listening to Radio Avalon. K was staring at a floodlight just flickering on in the gloaming. The techno track on the radio made a “bweep” sound. K looked at the radio, then at the floodlight, and murmured, “It’s bweeping at the sun.” Silence. Then I leapt out of the car like a scalded cat, ran around in a circle and projectile vomited. Number three, the drugs weren’t duff. We were just impatient.

Peel wasn’t the only famous person we saw. In those days it was a lot easier to blag backstage passes, to sit in that sacred space between the stages, watching the recognisable faces wander by. One year we found a sofa there and carried it to just outside the BBC outside broadcast unit, where Annie Nightingale was filing her radio report from the frontline in those pre-TV coverage days. We sat there for her whole show, staring intently at her. Afterwards she emerged with Pulp front-man Jarvis Cocker and K and I sprang up to talk to them. “I enjoyed your show earlier,” I told Jarvis. He looked at me curiously. “I haven’t been on.” Time becomes a loop. I was befuddled. “When are you on?” Curiouser and curiouser. “Who do you think I am?” “You’re Jarvis Cocker!”

“Mate,” whispered K. “He looks nothing like Jarvis Cocker.” Later, or maybe another year completely, we did indeed see Jarvis Cocker. He was helping his aged mother negotiate a puddle of mud. I’m convinced about that, but writing it down in black-and-white it doesn’t sound very likely.

Those Nineties years we saw a lot of celebs. A bleached-blond Robbie Williams playing football with a host of indie stars backstage, just before he announced he was quitting Take That. Standing in the queue for the loos with Noel Gallagher, exchanging a terse, “All right?” We glowered at Caitlin Moran, who was a journalist, like we were, and young, like we were, but who seemed to have the life we could only buy into for a Glastonbury weekend.

We lay under Dreadzone’s tour bus to get away from the sun, or the rain, or maybe the moon. We could see a celebrity, a huge name, massive. He was off his tits. “We should help him,” suggested K. We couldn’t move. We didn’t move until Dreadzone’s roadie found us under his bus. He coaxed us out by giving us a medal. For protecting the Queen, apparently. As far as I recall.

Up in the fields away from the maddening crowds watching the bands the real Glastonbury always lay. One year – maybe every year, I don’t know – there was a bearded man in round hippy glasses and a pair of Mickey Mouse ears who lay propped up on one elbow outside a tiny dome tent for the entire weekend. There was a sack – The Sack – quivering and communicating via what sounded like a kazoo. “What planet are you from?” I demanded shrilly, my anxiety rising as The Sack kazoo’d at me in quite an antagonising manner. “What planet are you from?”

We calmed down by watching a stone circle full of dreadlocked traveller types playing aboriginal instruments in a nerve-jangle discordance at the very top of the site. “Didgeridoo I not like that,” one of us said, and we ran screaming and laughing down to meet the falling night.

The robe of night added a new dimension to Glastonbury, somehow re-configuring its familiar daytime paths and layout to create a confusing, revolving chess board where it was impossible to get your bearings. Desperate not to miss a gig we were sure we were late for, we stopped a man in the darkness. “Mate, can you tell us where Primal Scream are on?” Exasperated pointing. To fifty yards away. “It’s there. This is the third time you’ve asked me, lads. You’re walking in a circle.”

When you arrived at Glastonbury you left the real world behind. No mobile phones, no internet. No contact with the outside world. But sometimes the outside world intruded, and it felt weird and other and positively unreal. T, his face bright red from the blazing sun, met us for a beer on the Sunday one year. We were too far gone to process what he was trying to tell us. “Mike Tyson. Evander Holyfield. Bit his ear off and spat it on the deck.” We were horrified.

Of course, it wasn’t all fun and games. We attended the medical tent twice, I think, that whole decade. One year, early on, I queued to see a doctor and yelled, “My heart is beating twice the speed it should be and I haven’t had any drugs!” I was advised to go and have an ice cream. It made me feel much better.

On the last Glastonbury, which must have been 2000 (apparently David Bowie was on. Apparently I saw him. I have no memory of this, which distresses me now), K had a bit of a moment. We saw a German doctor. She said, “Ze problem is, you haff fried your brains.” Did she speak in that comedy accent? Did she even say those words? I remember it vividly, so she must have.

It’s Glastonbury o’clock. I won’t be there. I’ll be watching it on TV, though, muttering about what a commercial cattle market it is, and thinking about these things, which are a fraction of what I can remember, which in turn must be a fraction of what actually happened.

“But what memories we made!” I said to K as we drove off the site in 2000, knowing it was our last Glastonbury. Actually, I don’t think I did say that, I think the phrase just stuck in my head when I wrote it at the top of this piece. But I do know K, or maybe I, said this: “Glastonbury drugs stories, mate. Like other people’s holiday photos. Nobody’s interested.”

Then he pulled over in a lay-by, vomited, and insisted I drive the rest of the way home.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments