The Who’s Pete Townshend: How Keir Starmer confronted me about ‘child pornography’ on my computer

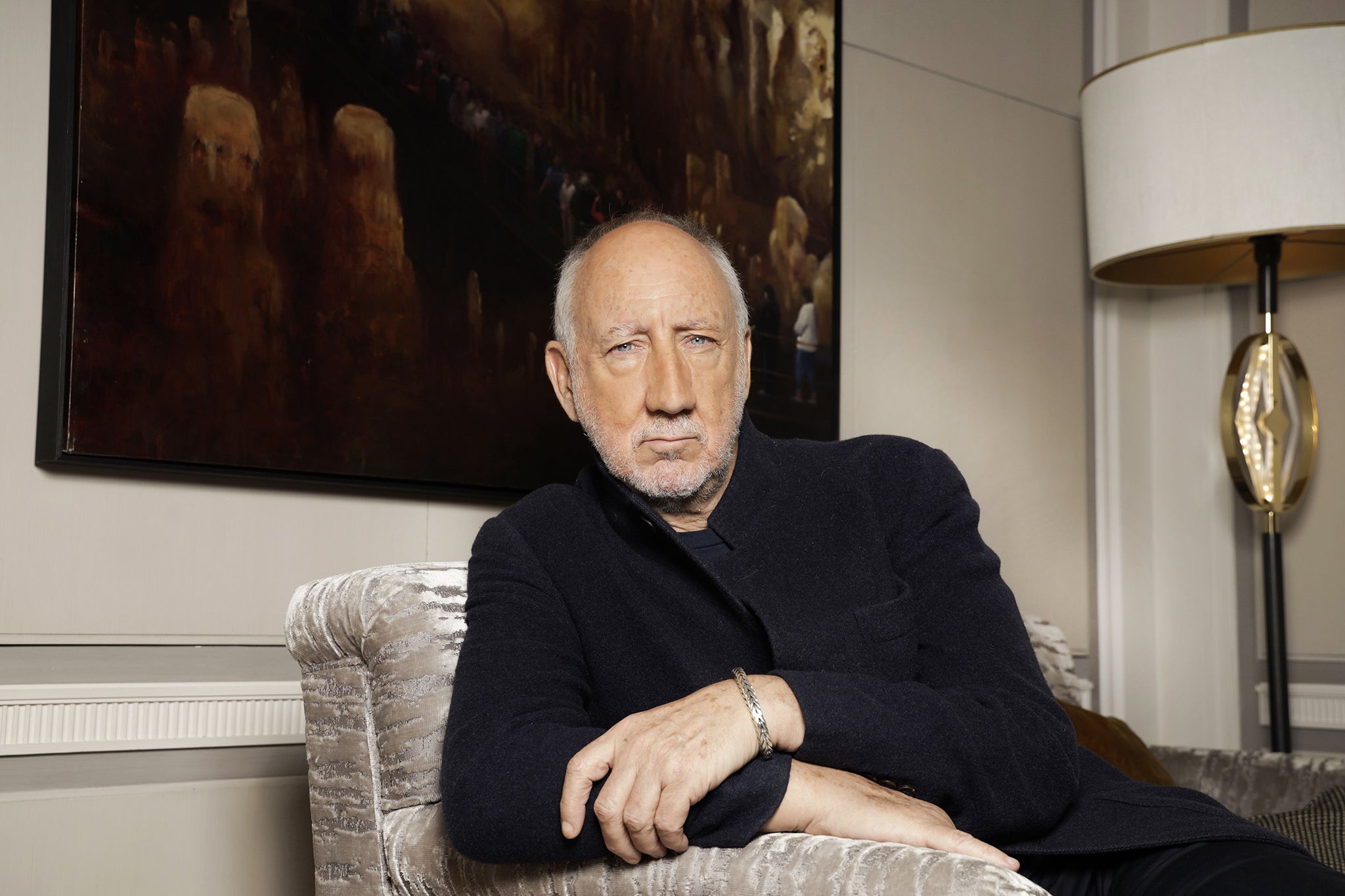

The guitarist talks to Kevin E G Perry about his 2003 arrest, his Seventies eco-meltdown rock opera, and how he feels about Rishi Sunak’s Tories

Pete Townshend had a vision. In 1970, in between writing Tommy and Quadrophenia, the then 25-year-old guitarist and songwriter started work on a rock opera set in a Britain suffering ecological collapse. With pollution choking the air, an autocratic government keeps the population docile with a constantly streaming entertainment network known as “The Grid”. Townshend called this ambitious project Lifehouse, but when plans for a movie version fell through and it became clear that even his bandmates were struggling with the convoluted plot, he admitted defeat and repurposed the bulk of the music for a conventional rock album, Who’s Next. Bookended by a pair of indelible anthems, “Baba O’Riley” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again”, the record, born of compromise, is often considered The Who’s finest work.

Now, over half a century later, the band have released an expansive 11-disc box set, showcasing not just the majesty of Who’s Next but also a trove of Townshend’s home demo recordings that sketch out what Lifehouse – now called Life House – might have been. The timing seems apt. On the day Townshend and I speak over video call, the prime minister has just announced the rollback of a swathe of key environmental policies across the UK. As miserable as the news is, I can’t help but ask whether Townshend gets some sense of vindication from knowing he saw this future coming all those years ago.

“F***!” he replies, gloomily. He’s at home in the English countryside, wearing a black beanie and some serious-looking headphones. His white goatee is neatly cropped, and he has the air less of a veteran rock star than of a particularly curmudgeonly academic. “I don’t know about Rishi Sunak,” he continues. “I don’t know about the Tory party, per se. They say, when you get older, you drift from being on the left to on the right. I suppose there was a gentle drift with me. I’m 78, and between 60 and 70 I think I was starting to drift slowly to the right, but... f***!” That expletive is followed by a reckless outburst of anger: “I would line them all up and shoot them.”

He shrugs off the idea that it took any great powers of prediction to spot environmental catastrophe on the horizon in the Seventies, but looking back at his work on Life House, he is impressed with how clearly he foresaw the all-consuming rise of the internet. “If there’s any prescience there, it was certainly the tech stuff,” he says, “That, really, I have to hand over to the teachers I had at Ealing Art School.”

Townshend was born in Chiswick on 19 May 1945, 10 days after the surrender of Nazi Germany brought an end to the Second World War. From the age of 16, he spent three years at art college studying under progressive, tech-savvy artists like Harold Cohen, who in 1973 invented a ground-breaking computer program, Aaron, that could create original paintings. Back in the early Sixties, “these guys were predicting the coming of computers”, remembers Townshend. “They predicted that computers would radically change the way that artists operated, including musicians, and that they would also change language and communications.”

Townshend soaked up those lessons, and gives the impression that he could quite happily have spent his life as a graphic artist or a teacher himself. Instead, the bright lights and raw energy of rock’n’roll were calling. He dropped out of art school in 1964 to focus on The Who, writing their first hit “I Can’t Explain” when he was 19. The following year the band released its debut album, My Generation, led by the proto-punk snarl of the deathless title track. Townshend’s songwriting ambitions grew quickly. “From the very beginning of The Who’s career, I started to play around with the idea of song cycles,” he points out. “Particularly with the mini-opera on The Who’s second album A Quick One, While He’s Away, and then with Tommy, and then subsequently practically everything I’ve ever done.”

Tommy, released in May 1969, was The Who’s fourth album. For Townshend, the sprawling rock opera about a boy rendered deaf, dumb and blind by trauma who becomes a messianic star represented a major creative breakthrough. That August, The Who performed the album in full at Woodstock. Townshend famously had a bad time on the day – getting dosed with LSD from a spiked cup of coffee, and grumbling about the mud. But his experiences there would help inspire a key Life House plot point: the idea that humanity might one day find its salvation in a cosmic rock concert. “When we played Woodstock, OK, I didn’t like it, but I knew what they were trying to do,” Townshend says. “They were trying to rise up, both politically and spiritually.”

A couple of weeks after Woodstock, The Who appeared with Bob Dylan and The Moody Blues at the Isle of Wight Festival. Again, Townshend thought he detected a palpable spiritual thirst from the audience – and a desire from the artists to quench it. “There was this moment when Dylan was bringing his folk-oriented political and sociological stuff, The Moody Blues were talking overtly about the spiritual path, and The Who had just released Tommy,” says Townshend.

However, the event’s utopian sheen soon evaporated. “I stayed there until it was finished, and by the time I left there was a sea of garbage,” he remembers. “Somebody with me, a photographer, said: ‘F***ing hell, it’s a teenage wasteland!’ so I wrote that down for a song! Our road crew went out and cleared the mess up. I remember being deeply disturbed by it all. Here we are, with an audience looking for uplift and inspiration and solace, because the world was not a particularly pretty place then either, and then they behave like scumbags!”

Perhaps counterintuitively, Townshend decided the answer was to give the scumbags more of a voice. “I wrote several essays for Melody Maker talking about the necessity for musicians to listen to what it was that the audience was really hoping for, and what the connections really were between audiences and performers,” he explains. “In other words, the normal idea of performance was that the performers are like gurus. I twisted it on its head, and made the audience the gurus. A lot of that sifted down into the Life House thesis.”

When it came to drugs, Keith Moon could swallow four horse tranquillisers

In an attempt to realise his theories, The Who set up a residency at London’s Young Vic theatre in 1971, where they hoped to dissolve the barrier between themselves and their fans. The performances were recorded, and are included in the box set, but whatever spiritual connection Townshend was hoping to establish failed to materialise. The audience, it seems, preferred to simply remain the audience.

More thrilling are the live recordings from the Civic Auditorium in San Francisco later that year, which capture The Who in full flight as they tour in support of Who’s Next. Wildman drummer Keith Moon had to have injections in his ankles midway through the show, something that has been attributed to his hard-partying diet of barbiturates with brandy. Townshend explains that Moon was in fact dealing with the after-effects of an incident on the way to the Isle of Wight Festival. “He’d broken both his ankles,” says Townshend. “The helicopter crashed as we were coming in to land. It started to spin, and the pilot told us to jump out. We jumped out in order, and Keith was last to jump out as the helicopter was rising up. He did the whole gig with two broken ankles, and he was still getting morphine injections in his ankles before shows for about a year after that.”

Townshend laughs when I point out that Moon still sounds phenomenal. “Yeah, he was an extraordinary man,” he agrees. “When it came to drugs, he could swallow four horse tranquillisers. I think it was elephant tranquillisers that finally got him.”

Moon died in Mayfair in 1978, at the age of 32. The Who carried on for another couple of records without him, but split in 1983 after Townshend called a press conference to announce he was leaving the band. That same year, he took a job as an acquisitions editor for Faber and Faber, working on several music books as well as publishing his own short stories, and later his memoir Who I Am and a novel, The Age of Anxiety.

In 2002, he published an essay on his website titled “A Different Bomb”, in which he described how he had stumbled across images of child abuse online and his attempts to raise the alarm. The following year he was arrested and subsequently spent five years on a sex offenders’ register after admitting he had used his credit card to access a website that claimed to host child sexual abuse images. He maintains he was only ever doing research with the best of intentions.

“You know, I made a mistake, but I think I did the right thing,” he says. “I was challenged by Keir Starmer, who was then in charge of public prosecutions, to either go to court to make my case clear or to accept a caution. I was terrified of going to court. I thought I would be used as a poster boy, so I refused. I took the caution. So legally, there’s an argument that I was guilty of what I was accused of, which was downloading child pornography, which I never did. In fact, I was campaigning and researching and trying to get to a place where I could be useful to point the finger at where it was coming from.”

He is acutely aware that the incident still casts a long, dark shadow over his public reputation. “When I do an interview, often the comments refer to it: ‘This guy should be in prison,’” he says wearily. “It comes up a lot. It’s part of my daily life, and it’s painful, but I know the truth, my wife knows the truth. She watched what I was doing. My essay ‘A Different Bomb’ is out there on the internet, so if people want to read where I was before my arrest, they’re welcome to do so.”

Rather than dying young like Moon, Townshend has instead been cursed with having to reach the age of 78 while being constantly reminded that as a teenager he wrote the line: “I hope I die before I get old”. These days, it’s safe to say Townshend is feeling his age. “I remember years ago I was at an Amnesty International event with the great left-wing peer Lord Goodman,” he says. “I had to take him to the bathroom, which was up some stairs, to have a pee, or try to. He said: ‘Pete, don’t grow old! I’m 89 now. All my friends are dead, I’ve had to write epitaphs for each of them, and now I can’t piss!’ There’s a bit of that going on for me.”

He adds that he’s discussed his encroaching mortality with his friend, the playwright Tom Stoppard, who is 86. “He’s in the same place,” he says. “He’s working on a play and he’s worried about running out of time. You know, one’s hands begin to shake, your brain gets fuzzy. As a creative, you feel the effects of old age may not affect your poetic creativity, but they certainly affect your ability to measure what the wider audience out there might want. It should be easier today, with social media, but it’s more difficult because people on social media are not telling the truth.”

In the time he has left, Townshend still hopes he might see Life House brought to the big screen. The new box set includes a gorgeously illustrated graphic novel telling the Life House story, but he accepts that it couldn’t possibly have the same impact today that it might have done in the early Seventies. “If it gets made into a movie, which it might do now, based on the graphic novel, it will not be as glorious as it would have been to have managed to tackle a kind of Beatles-Stones-Pink Floyd-Moody Blues-Who event that brought all of this energy together and had a glorious sense for the audience that they were part of a spiritual uprising,” says Townshend, never afraid of appearing too ambitious. “That’s really what I was hoping for, arrogantly, looking back.”

The Who’s ‘Who’s Next/Life House’ box set is out now

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks