‘The Stones are their attitude, and that attitude is Anita’ – the women who transformed The Rolling Stones

Elizabeth Winder’s ‘Parachute Women’ tackles the myth of the partner as ‘muse’. She tells Jim Farber why Marianne Faithfull, Bianca Jagger, Anita Pallenberg and Marsha Hunt were much more than that

A few years ago, when author Elizabeth Winder got the idea to write a book about the women in The Rolling Stones’ inner circle in the Sixties, she kept having the same thought: “These women have such incredible and dramatic stories to tell,” she says, “I felt sure that somebody must have written a book about it already.”

In a sense, they have. Of the main women covered in Winder’s book, Marianne Faithfull, the most famous of the Stones’ former lovers, has written two memoirs; Marsha Hunt, who had a child out of wedlock with Mick Jagger, has written one; while Anita Pallenberg, who was Keith Richards’s partner in the Sixties and Seventies, has had a book written about her, as has Bianca Jagger. Winder, who did not speak to any of those women, nor to any of the Stones, for her book, wound up borrowing from all those sources. Yet, none of them came up with the particular, and provocative, premise of Winder’s work, titled Parachute Women.

The book is named for a Stones’ song from their 1968 album Beggar’s Banquet. It’s the central contention of her book that the women she covers – primarily Pallenberg and Faithfull – were crucial in teaching “a band of middle-class boys how to be bad”. It was the women’s influence, intellect and sophistication that transformed the relatively provincial and conventional Stones of the early Sixties into the bohemian revolutionaries who would bewitch the world several years later. “These women were way cooler than the Stones,” Winder says. “Mick and Keith wound up becoming some of the coolest people on earth, but they got that from them.”

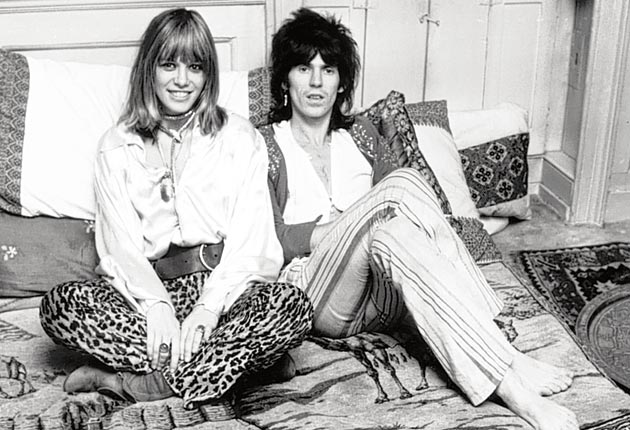

The story of the women’s influence started, as so many Sixties stories do, with drugs. Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brian Jones had never done any illegal substances in the early Sixties. “The only coke they had was mixed with rum,” Winder wrote. All that changed one day in 1965 when they met a young German-Italian model and actress named Anita Pallenberg whose first move was to pull out a spliff from her purse and casually ask Jones, in a heavy European accent, “vant to smoke a joint?”

Thanks to her, the three Stones wound up spending that entire night blindingly high. While the Stones already knew lots of models – Jagger was then dating Chrissie Shrimpton – Winder says Pallenberg was a different character altogether. Unlike the strait-laced Shrimpton, Pallenberg had an aloof hauteur, a louche air and an unsinkable confidence that made her an ideal fit for the worlds she moved in before she met the Stones. That included a time in Italy living la dolce vita, and a stretch in New York in both the demi-monde of Andy Warhol’s “superstars” and the avant-garde world of The Living Theatre company. “She was already a pirate,” Winder says.

Pallenberg’s first interest in the band was Jones, who had the best hair and was the most open to a woman with a natural bent for adventure. He also had the most sexual experience. “He really had it down and they didn’t,” Pallenberg told author David Dalton for his book The Rolling Stones: The First Twenty Years. “Except for Brian, all of the Stones at that time were really suburban squares.”

“How Anita came to be with Brian is really the story of how the Stones became the Stones,” Faithfull wrote in her memoir, Faithfull. “(Anita) almost single-handedly engineered a cultural revolution in London by bringing together the Stones and the jeunesse dorée (the young rich).

The result helped create a cross-pollination of classes – mixing the middle and the upper – otherwise unseen in London at the time. Rock stars became equal to aristocrats, aided in the Stones’ sphere by Pallenberg’s access to the worlds of high art and hip people of wealth, including members of the Guinness family. Pallenberg also encouraged Jones’s creative side, evident in his newly expansive contributions to the Stones’ albums of ’66 and ’67, Aftermath and Between the Buttons. Her self-regard seemed unshakeable, and the result proved infectious. “If you were around her and she was on your side, she would boost your confidence almost in the way a dangerous drug boosts your confidence,” Winder says. “It makes you feel like you can get away with anything.”

Faithfull came into the band’s orbit in 1964 while attending a party for the band. Their manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, spotted her and famously said, “you have a contemporary face. I can make you a star.”

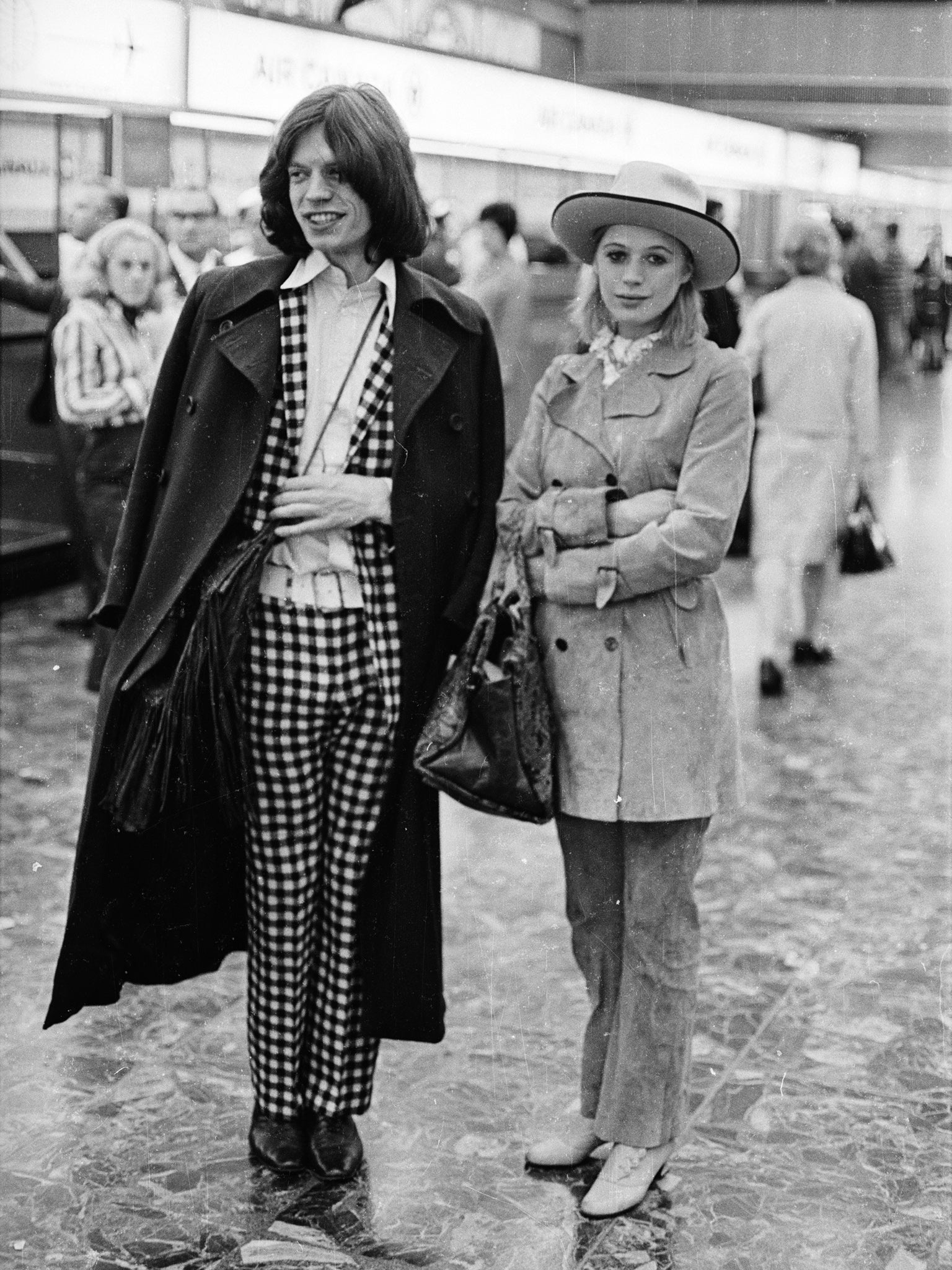

Faithfull had already done some singing in folk clubs, but she turned her nose up at popular music, preferring the cabaret songs of the Weimar Republic. Even so, Oldham’s offer to have the Stones write a single for her proved enticing, especially given the beauty of the melody and the unexpected maturity of the lyric they came up with for the song: “As Tears Go By”. Faithfull has often said that she wasn’t initially attracted to Jagger. At first, he kept his distance from her as well. But over time, he became fascinated by her wealth of literary knowledge, and her wide cultural references, two things he sorely lacked. “She’s very much a writer in sensibility,” Winder says. “Always at the forefront of her mind is this infectious enthusiasm for literature and poetry.”

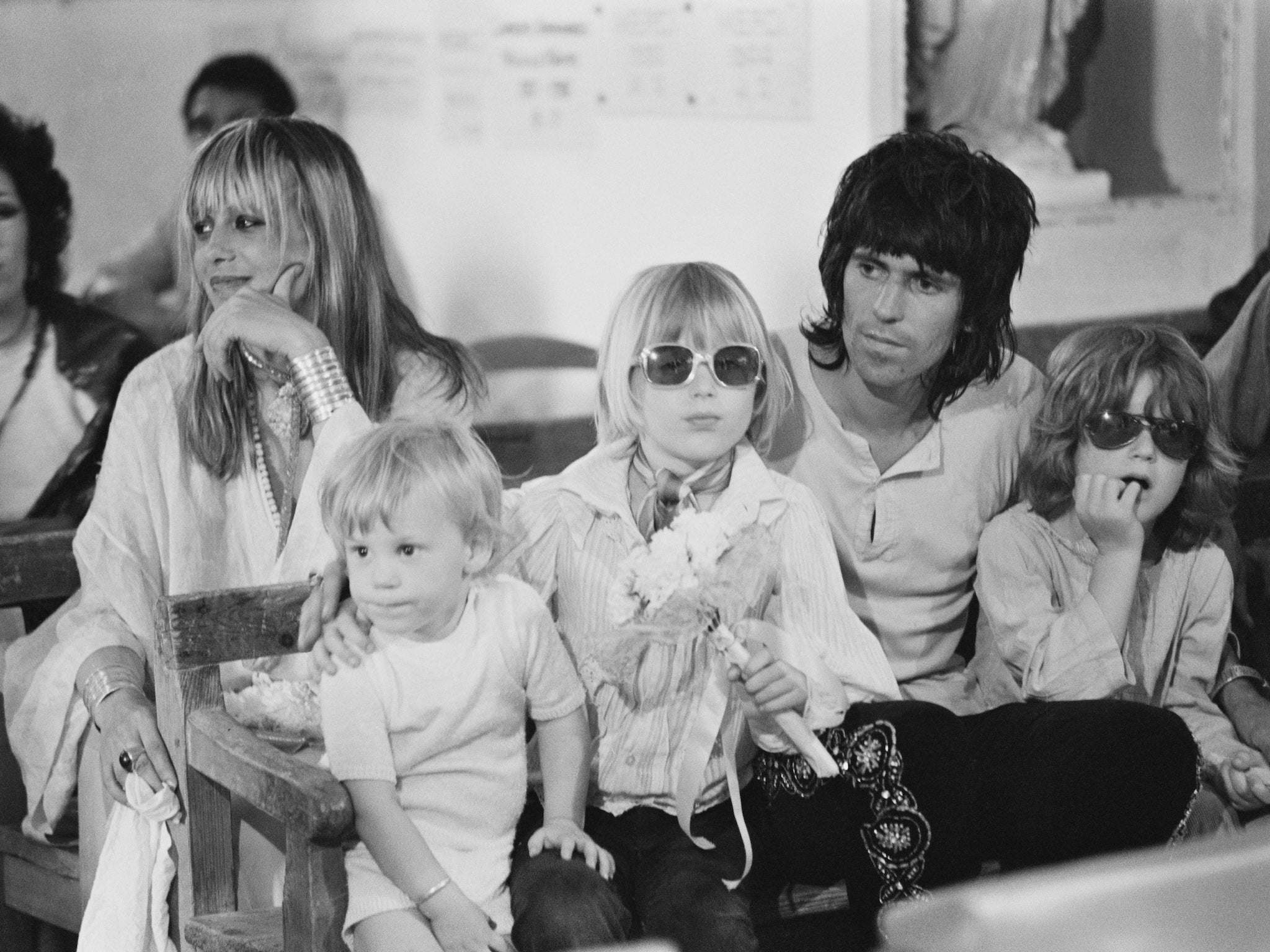

The books Faithfull read became inspirations for Jagger’s lyrics, in the same way that Pallenberg’s love of all things transgressive and outrageous informed everything from Jones’s growing interest in S&M and the occult to his foppish outfits. Things took a dark turn, however, one night when Jones suddenly turned violent and punched her in the face, encouraging a shift in Pallenberg’s attention, away from him and towards Richards. The switch in her affections has been seen as a contributing factor in Jones’s decline into drug use and behaviour that became so erratic that it led to his dismissal from the band shortly before his death in July 1969. Meanwhile, Richards seemed to find a role model in Pallenberg. He began to wear her clothes and her jewelry, including the skull ring that later became a signature. “A lot of people think that Keith was always the Keith that we know,” Winder says. “But if you look at pictures of him from the early days, he’s the most buttoned-up looking one of the bunch.”

If you were around Anita and she was on your side, it made you feel like you could get away with anything

While Pallenberg may have had the deepest effect on Richards’s developing outlaw character, Winder believes she affected the tone of the whole band. “The Stones are their attitude, and that attitude is Anita,” she says.

Sceptical fans may question just how deep that view goes, given the fact that Pallenberg didn’t write a single song for the band, nor did she play a single instrument on their recordings. (She did, however, tell them to remix Beggar’s Banquet before releasing it, which they promptly did). “Style is a big part of the Stones’ music and in my opinion, you can’t neatly separate the two,” Winder says. “Some of the swagger in the music could not have happened if they weren’t adopting that character through the influence of these women.”

At the same time, that rebel character, when expressed by a woman, was viewed very differently in the press than when expressed by a man. In 1967, when The Stones went through a scandalous drug bust involving Jagger, Richards and Faithfull, the men were viewed as cool rebels while the woman was seen as a tarnished harlot. “Mick and Keith came out of it with an enhanced bad boy varnish,” Faithfull wrote in her memoir. “I came out of it diminished, demeaned, trampled in the mud.”

She got the same treatment two years later while recovering from an overdose of barbiturates in Australia while Jagger was acting in the film Ned Kelly. It inspired a torrent of lurid headlines. Pallenberg received a similarly condemning treatment from the press. “The behaviour that was applauded when Keith did it, was written about as vile and horrendous when Anita was doing it,” Winder says. “The misogyny that was just accepted at that time is pretty unbelievable.”

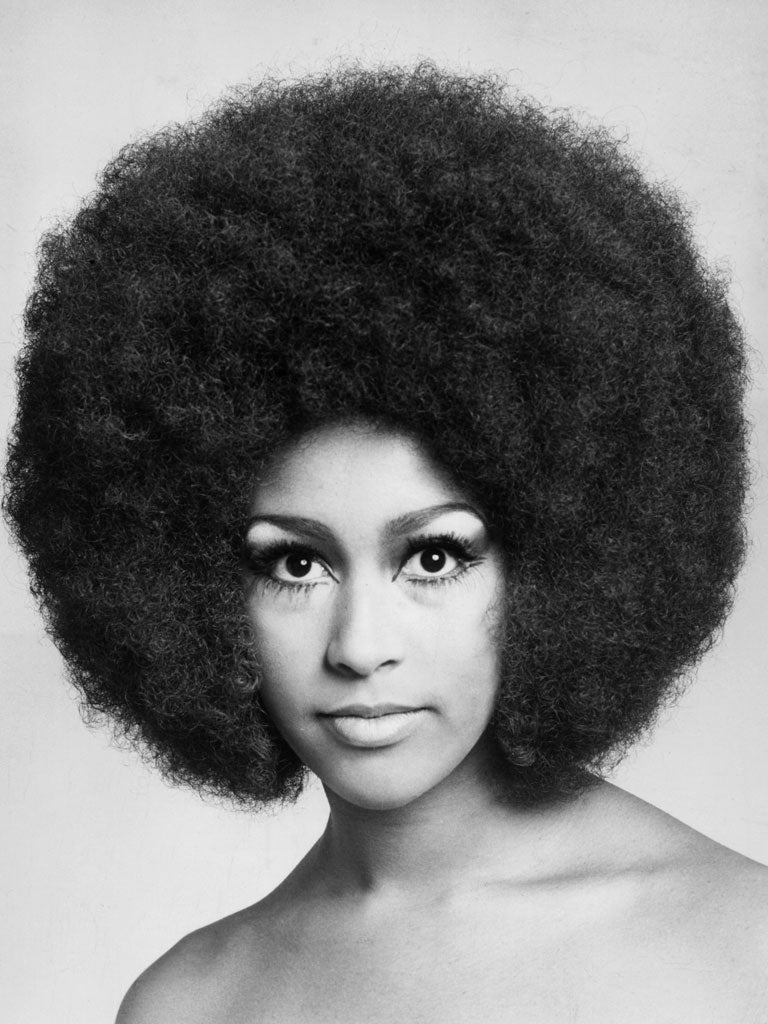

When it came to Marsha Hunt – a Black American singer and actor who was involved with Jagger after his relationship with Faithfull ended – it wasn’t just sexism that came into play but also racism. As a Black female rocker, she was not taken seriously by the music industry at the time and, in her modelling days, she was always lit to make her skin look lighter. Her first brush with the Stones came in 1969 when Jagger asked her to pose provocatively for an ad for “Honky Tonk Women”, a gig she turned down flat. “There was an element of fetishism to it, which is why she refused,” Winder says.

She did, however, become involved with the singer and had his child in 1970, after which the relationship promptly ended. Jagger provided some child support, but Hunt considered it meagre. At one point, she ended up living on welfare while raising their daughter. Meanwhile, the press “treated her as some woman who was just trying to grab money from him, as if she got pregnant as some sneaky thing,” Winder says.

What makes the word muse so upsetting is the passive sense that their whole life was just to inspire these men

The book portrays Jagger’s relationship with the Nicaraguan-born Bianca Pérez-Mora Macías in a way that, ultimately, doesn’t seem that much better. The couple married in 1971; Bianca lent the rocker an international flair and some political awareness but, as Winder writes, she “fled her totalitarian state only to be trapped by a totalitarian husband”.

Meanwhile, Faithfull went off the deep end with drugs, living for a while on the street in London. Winder blames her slide on several factors, including the profound boredom she experienced as a highly talented woman playing the role of lady-in-waiting for a rock God, as well as the awful press she received. “She was still so young,” the author says. “I blame him (Jagger), I blame the press. I blame everybody but her.”

Of course, Faithfull made a major comeback in 1979 with the smash album Broken English and has gone on to enjoy a long and highly respected career as a singer and, occasionally, an actor. Pallenberg, whose relationship with Richards lasted until 1980, and with whom she had three children, didn’t have much of a career after her recovery from heroin addiction, though she did act in more than a dozen films during her lifetime. (She died in 2017 at age 75). According to Winder, career ambition was never Pallenberg’s interest. “Her art was her life,” she said.

That artistic approach to life is what Winder believes makes these women so much more than the mere muses they’re often portrayed to be. “What makes the word muse so upsetting is the passive sense that their whole life was just to inspire these men, as if they weren’t doing anything on their own,” she says.

That’s a key reason Winder named her book Parachute Women to begin with. “It’s like these women were floating down from the sky,” she says. “In a metaphorical way, they had to bring themselves down to earth to bring the Stones up. Ultimately, they were always on a higher level.”

‘Parachute Women’ is being published on 24 July by Hachette Books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments