Has the North stolen London’s arts crown?

Manchester’s £365m arena Co-op Live may have had an inauspicious start, with power failures, cancelled gigs and a resigning boss but, asks Laura Barton, is the glitzy new venue’s arrival a sign that the North is finally challenging the South when it comes to arts and culture?

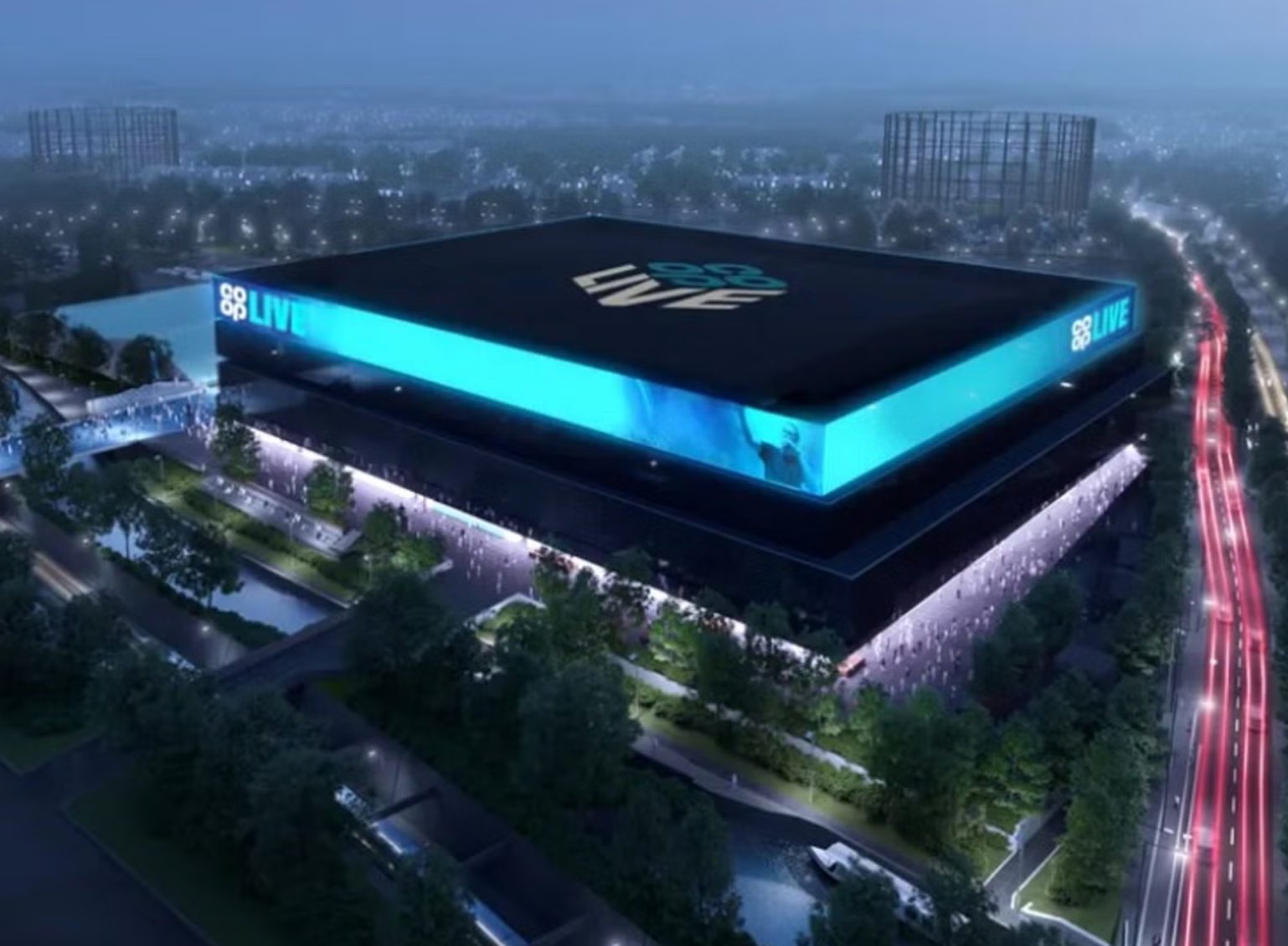

The glittering launch of the largest-capacity entertainment arena in the UK, Co-op Live, did not quite run as hoped. This week’s opening shows at the £365m Manchester venue – two sold-out turns by the comedian Peter Kay – were rescheduled owing to issues with the building’s power supply. The newspaper headlines spoke of “catastrophe”, “controversy” and “farce”. The arena’s general manager duly resigned.

Still, once the dust has settled and the doors are open, few may remember the hiccoughs of the Co-op’s early days. A 23,500-capacity arena situated next door to Manchester City’s football ground, it will play host to acts such as Olivia Rodrigo, The Killers and Nicki Minaj, plus local favourites James, Elbow, Liam Gallagher, and Take That. It will be the only UK venue to host the Eagles on their farewell tour this summer, and it’ll also be home to this year’s MTV Europe Music Awards. As an extra flourish, its design was developed in consultation with Harry Styles, who is also one of its backers.

Its scheduled opening coincided with news of another major arts centre’s ongoing woes – this one in the capital. As the stories unfolded, they became not just a tale of two venues, but a tale of two increasingly divergent cities – one in a cultural ascendance, the other in a state of faint humiliation.

The head of London’s Southbank Centre, Elaine Bedell, gave an interview in which she set out the dire financial situation faced by the multi-venue cultural complex, estimating some £50m would be needed to fix leaking roofs, broken lifts and damaged paving. There was no way, she said, that they could renovate the building and deliver a rich and diverse arts programme.

To compare the two venues is not entirely fair – the Southbank is a registered charity, its remit far broader than that of the Co-op, a commercial enterprise. Over the 70 years of its existence, it has become known for its expansive programming, home to the avant garde, classical and electronic music worlds. The weeks ahead will see everything from a restorative vocal workshop with the drone choir NYX to this year’s Meltdown Festival, curated by Chaka Khan, via exhibitions by artists Mary Kuper and Tavares Strachan, and a somatic movement tour of a collection of contemporary sculpture.

Still, it’s hard not to place these two venues side by side – the gleaming new hero and the bedraggled cousin – and see the difference between them as part of something greater: a cultural shift away from the capital and out into the regions. After all, in 2019, when London’s arts institutions found their public funding cut in the name of the government’s “levelling up” agenda, the Southbank, down £1.5m, was the city’s biggest loser.

The rerouting of arts funding away from London has brought further investment and attention to Manchester, particularly. The city seems now to be establishing some vast-scale Culturopolis: Co-op Live joins the city’s AO Arena, where a recent £50m renovation expanded the venue’s capacity to 23,000. And when the £242m Factory International opened six months ago, it became the UK’s biggest investment in a cultural project since Tate Modern (a short walk from the Southbank Centre), nearly 25 years ago.

Further investment is planned: Manchester’s Culture in the City project received £20m from the levelling up fund last year, and new enterprises will sit alongside already successful ventures such as the performing arts space HOME, The Warehouse Project, and Manchester International Festival, plus a host of smaller venues throughout the city.

Inevitably, the effect has rippled outward: in the last six months, the Michelin guide announced its 2024 winners at the Midland Hotel, Chanel staged its annual Metiers d’Art show in the Northern Quarter and, having been informed it must leave the capital or lose its Arts Council funding, English National Opera announced it would make Manchester its new home. It is, Chanel declared, “one of the most effervescent cities of pop culture”. Or, as Co-op Live’s recently departed GM Gary Roden described the venue’s ambitions to poach the UK’s major cultural events: “There’s no reason why the Brits can’t come up North.”

But in Roden’s words lies the deeper part of this story. Note that his comment was not directed at anyone geographically above Manchester, but squarely in the direction of London, and the more affluent South East – a “come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough” taunt in the long-running skirmish between England’s North and South.

With much of the investment landing in the North, we met with the old assumption that to be Northern is to be working class, and to be working class equates to being culturally uneducated

I suspect when the Tories devised “levelling up” this was precisely the type of rivalry they hoped to stoke. On the one hand, the grief of the capital’s great cultural institutions was understandable; on the other, the subsequent debate seemed to suggest that funding arts ventures outside of London would be a matter of placing pearls before swine. And, with much of the investment landing in the North, we met with the old assumption that to be Northern is to be working class, and to be working class equates to being culturally uneducated. To which I suggest you read Jonathan Rose’s aptly titled The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes and think again.

But look more closely at the grand levelling-up plan and you might come to see it differently; as a government pitting the capital against the regions as a distraction, while they raided national arts funding – which has close to halved since the Tories came to power, and left us all culturally bereft.

Inevitably, London will fight back. Already, there are rumours of another new venue in Hammersmith, developed by Co-op Live’s owners, which will eclipse Manchester’s new arena in scale and grandeur. And it’s hard not to assume that this will tip the rivalry back the other way once more. That, after this era of great Northern fanfare, all the focus and the money will quietly drift back to the capital.

Without long-term, deep-rooted investment, one wonders what will happen then to the great cultural buildings of the regenerated North. Whether the gleaming new arenas and creative hubs might meet the same fate as the factories and warehouses of the city’s industrial heyday. Lying empty and still for so many years, waiting to become some future generation’s luxury apartments.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks