Nine Inch Nails’ Pretty Hate Machine at 30: How Trent Reznor survived a label feud to create one of the definitive debut albums

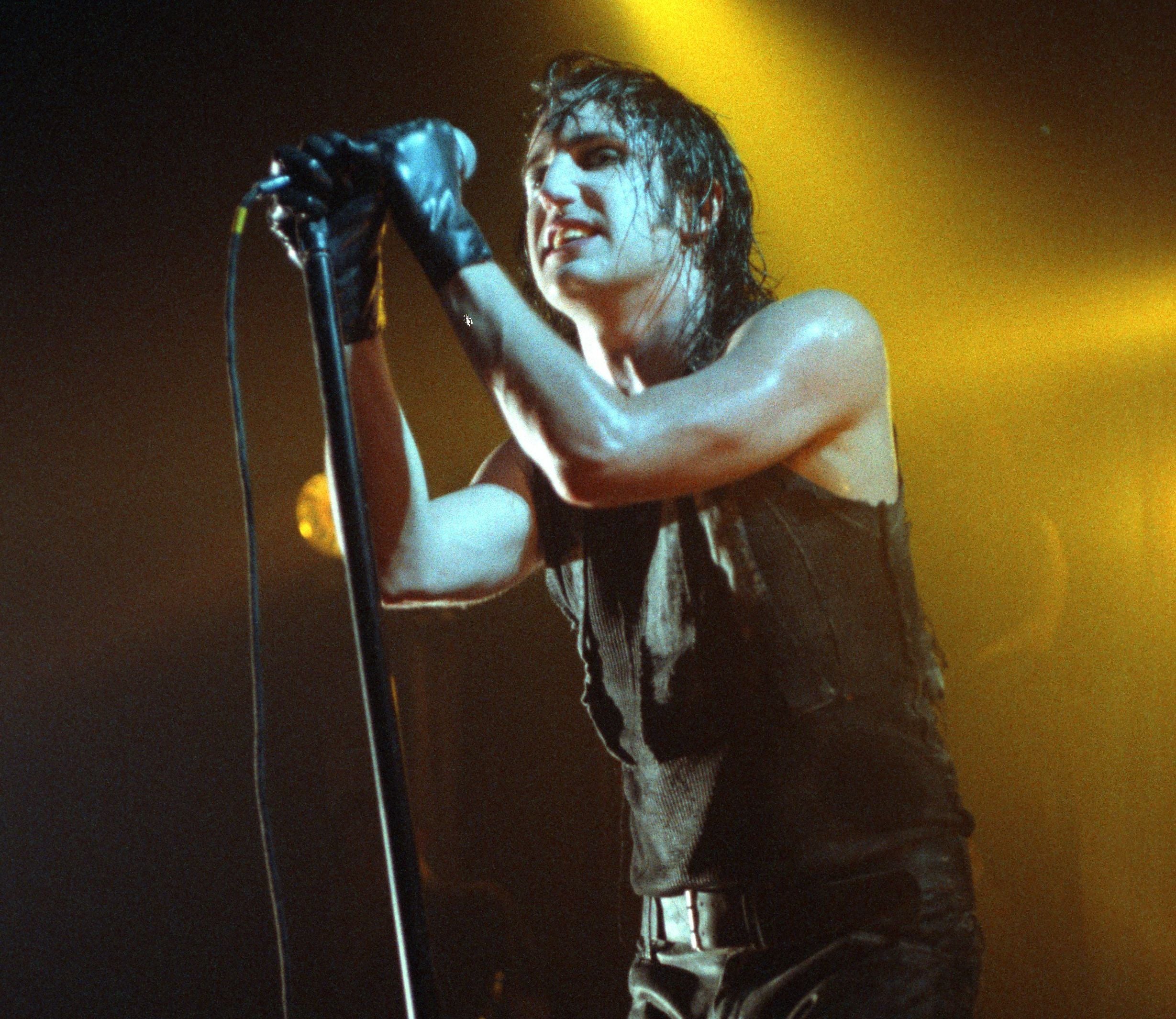

Thirty years ago, the zeitgeist was temporarily hijacked by angry young musicians driven by one artistic imperative above all others: the urge to not fit in. Ed Power reflects on one of the best records of its time, and how it keeps coming back in strange ways

Trent Reznor didn’t know whether to laugh, weep or punch the wall. It was the dawn of the Nineties and the 24-year-old former janitor’s industrial rock project, Nine Inch Nails, was becoming an unlikely mainstream phenomenon. Out of the blue he had been summoned for a sit-down with his record label at their offices, in the shadow of the Chrysler Building in Manhattan.

The subject at hand was the promotional film for the forthcoming single, “Sin”. Arranged on the table was a catalogue of models. “Pick a girl to be in your next video,” TVT Records owner Steve Gottlieb told Reznor, gesturing towards the book, which contained dozens of headshots.

Posterity does not record Reznor’s response. We do know that the video to “Sin” featured pierced genitals and a wrist-bound Reznor with a bag over his head, being led by a woman who was naked apart from a halogen lamp. It was not quite what Gottlieb had in mind, and that was the point.

“I hate the videos on MTV,” Reznor explained, shortly before “Sin” was unleashed upon an unsuspecting and appalled world. “Someone asked me to name my five favourite videos. I can’t name two.”

Thirty years ago, the zeitgeist was temporarily hijacked by angry young musicians driven by one artistic imperative above all others: the urge to not fit in. In 1989, Nirvana released their first album, Bleach. Pixies put out their definitive weirdo-rock document Doolittle. That May, the Cure gave us their hermetic masterpiece, Disintegration. Each was in its own way a treatise on isolation, juvenile angst and living inside your head.

Far less heralded at the time, yet no less influential in the long run, was Nine Inch Nail’s dissonant, almost transgressively catchy Pretty Hate Machine. As it marks its three-decade anniversary this week, it is clear that it belongs to that exclusive club of definitive debut albums. It is very nearly perfect.

Reznor would record more important and more sonically ambitious work (and he would win an Oscar for his score to David Fincher’s The Social Network). But everything he is about as a musician and as a person – the exhilaration, the darkness, the relentless protean rage – is present and correct in Pretty Hate Machine. In the context of the grunge explosion that followed and the post-Columbine massacre culture wars into which Nine Inch Nails were dragged, through no fault of their own, it isn’t an overstatement to herald it as one of the most important records of its time.

And it keeps coming back in strange ways. Billie Eilish’s “Bury a Friend” carries huge glittering swirls of Pretty Hate Machine’s DNA. This year, the single “Head Like a Hole” was repurposed by Charlie Brooker in his latest series of Black Mirror. In the episode “Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too”, Miley Cyrus’s miserable pop star performs a gaudy facsimile of the track. When she finally achieves artistic liberation, she celebrates by signing the original in a dingy club. It is arguably the highlight of the entire season.

“Pretty Hate Machine set a precedent for NIN’s development, what you could almost call a blueprint for the NIN sound and aesthetic,” says Adam Steiner, author of the forthcoming Into the Never: Nine Inch Nails and the Creation of the Downward Spiral (published in early 2020). “It’s a musical blend of synth-pop sheen, post-punk abrasion and pop nous. Reznor wrote some very catchy singles – ‘Head Like a Hole’, ‘Down in It’ – full of lyrical and melodic hooks, while also building a wall of noise with electronic distortion and angry guitars. In some respects he prefigured grunge loud/quiet dynamics.“

Reznor was an unusual mix of fragile and supremely confident. As a Nineties megastar, he would share with Kurt Cobain an instinct loathing of and suspicion towards celebrity and its trappings. And he would eventually spiral into a near fatal drug addiction (he credited his friend and touring partner David Bowie for showing him the way back).

Yet growing up in Mercer, Pennsylvania and later Cleveland, Ohio (where he moved after dropping out of college), Reznor seemed to possess a sense of manifest destiny. At Mercer, he played in the high-school jazz and marching bands; later, trying to get his music career started in Cleveland, he taught himself rudimentary programming. He would perform almost every instrument on Pretty Hate Machine and record it himself on a battered Apple Mac.

Those who remember him from that time say that at no point did he come across as even vaguely acquainted with self-doubt. Reznor appears to have been one of those musicians – Morrissey, Madonna and the aforementioned Cobain also spring to mind – who were fully realised stars long before the spotlight had picked them out.

Still, his was by no means an overnight ascent. The years preceding Pretty Hate Machine found Reznor scraping a living as a janitor and assistant engineer at Right Track Studio in Cleveland. In his spare time, he would record demos at the facility. He’d tried to start a band in Cleveland. But he couldn’t find anyone willing to commit to his vision. So he did it all on his own.

“I kinda hung out in my room and wrote some songs,” is how he would recall that formative period. “At the same time I was working in a studio in Cleveland. This was the beginning of ‘88. During the course of that came up with the idea for Nine Inch Nails. I sent some tapes out, got a record deal.”

Those early Nine Inch Nails jottings were discordant and full of anxiety. Yet, even in rudimentary form, his songs were also incredibly catchy. Executives in New York and Los Angeles were sufficiently impressed to get on the phone and offer this kid from the sticks, who had apparently emerged from nowhere, a deal. Mystifyingly, Reznor would sign not with a major but with TVT, a tiny label founded in 1985 by Yale graduate Steve Gottlieb. It was a fractious relationship from the outset.

“When Gottlieb initially signed Reznor to TVT on the strength of demos, the self-assured label head presumed he was getting a pliable pop star in the making,” wrote Alternative Press editor Jason Pettiegrew in Glass Everywhere, an essay published with a re-release of Nine Inch Nail’s 1992 EP Broken.

“So when Reznor delivered the electro-excavation Pretty Hate Machine in early ‘89, Gottlieb was disdainful. He deemed Pretty Hate Machine a failure and told Reznor he was deliberating whether to release the album at all. When you consider the old adage that artists have their whole life to draw upon when they make their first record, Gottlieb had just said Reznor’s life experience amounted to nothing.”

To defend Gottlieb for a moment: Pretty Hate Machine was certainly a departure from the demos that had got Reznor signed. In the interim, Reznor had somehow persuaded producer big name Flood (Nick Cave, U2), among others, to work with him. And so he flew to London to master the album at Blackwing Studios in Southwark (where Depeche Mode recorded Speak & Spell).

“If you listen to Purest Feeling, an album of Pretty Hate Machine demos, you can hear evidence of the incredible journey the songs made from Cleveland to the world,” says Daphne Carr, author of the Pretty Hate Machine entry in the 33 1/3 series of literary takes on classic records.

“In the demo the song structures are there, as is the intense delivery, but there is a distinct lack of the kind of intangible, feral energy and spatial hugeness that, for instance, widens from a tiny shaker to a widescreen scream on the album version of “Head Like a Hole”. Reznor worked with the era’s masters of deep space and kinetic energy, and it’s clear that he was a keen student in the studio.”

Gottlieb could not have been any wider off the mark regarding the album’s prospects. Pretty Hate Machine sold and sold. Soon it was chugging towards platinum disc status (by 1992 it would shift more than 500,000 units in America alone). Yet with success, the caricature of Reznor as the misrerabilist’s miserababilist began to catalyse – a grab-bag of sad goth cliches personified.

It didn’t help that he always wore black and came across on stage as extravagantly tortured. Or that his lyrics could veer from nihilistic into full-blown self pity. Consider “That’s What I Get” and couplets such as “Just when everything was making sense/ you took away all my self-confidence/ now all that I’ve been hearing must be true/ I guess I’m not the only boy for you.”

“It is possible,” says Daphne Carr, “to cherry pick specific lines to focus on Pretty Hate Machine as an album about a bitter, jilted lover who refuses to see their own faults or consequences of their own actions – playing a helpless victim of the archetypal pop ‘evil woman’. But, let’s put this in perspective; so are a lot of Bob Dylan songs.

“That’s not to discount the truth that Pretty Hate Machine could be interpreted to aid the cause of misogynists on- or offline, but only to say that quite a bit of popular music can be used in that way. I mean, Pharrell JUST realised ‘Blurred Lines’ encourages rape culture? The jukebox of misogynist jams is unfortunately stacked deep with hits.”

The unfortunate postscript to Pretty Hate Machine arrived in two distinct chapters. The first was in 1993 as Reznor started on Nine Inch Nail’s second album, The Downward Spiral (recorded after he had extracted himself from his toxic relationship with TVT). Fame had become a hooting primate on Reznor’s back. He was a natural rock star. Nonetheless, celebrity was an anathema to him.

Moreover, the bleak world view that provided the backdrop to Pretty Hate Machine had turned into a pulsating black hole. Whatever forces he had unleashed with his first record would threaten to rip him asunder second time around.

“Reznor did not have such a hard time, personally, during this phase of his career, although he quickly found himself mired in the touring and recording industry mill,” says Adam Steiner.

“It was as he underwent the relatively gruelling process of making The Downward Spiral, and subsequent multiple worldwide tours that were constantly extended, that his drug and alcohol use began to accelerate towards addiction. A crash would later come in 2000 with an overdose, apparently too much cocaine in London before a show, leading to many years of rehab and personal recovery.”

And then, in 1999, the Columbine high-school shootings occurred. After Eric Harris (18) and Dylan Klebold (17) murdered 12 students and a teacher one sunny April morning the media scrambled to make sense of the atrocity. Rather than focus on the glaring question of gun control, they seized upon Harris’s love of Nine Inch Nails and of Reznor’s protege Marilyn Manson. In a diary entry in which he fantasised about luring a girl to his room, Harris quoted Reznor’s lyrics. The outcry that followed was depressingly predictable.

“Columbine happened 10 years after Pretty Hate Machine, in the waning height of NIN’s mass appeal, and was one of the main bands that media focused on as part of the murderers’ fandom,” says Daphne Carr. “Because Columbine was a predominately white middle-class school, the media did not blame the parents, school, or community – as they likely would have had the murderers been [people of colour] – but rather individualised the blame as the consequence of the boys’ psychological problems, which they conjectured had been sharpened by music and video games.

“The consequence was that there was a national moral panic in high schools and homes where teens’ NIN and Marilyn Manson fandom was seen as ‘probable cause’ for surveillance, preemptive punishment or banishment, and/or therapeutic interventions.”

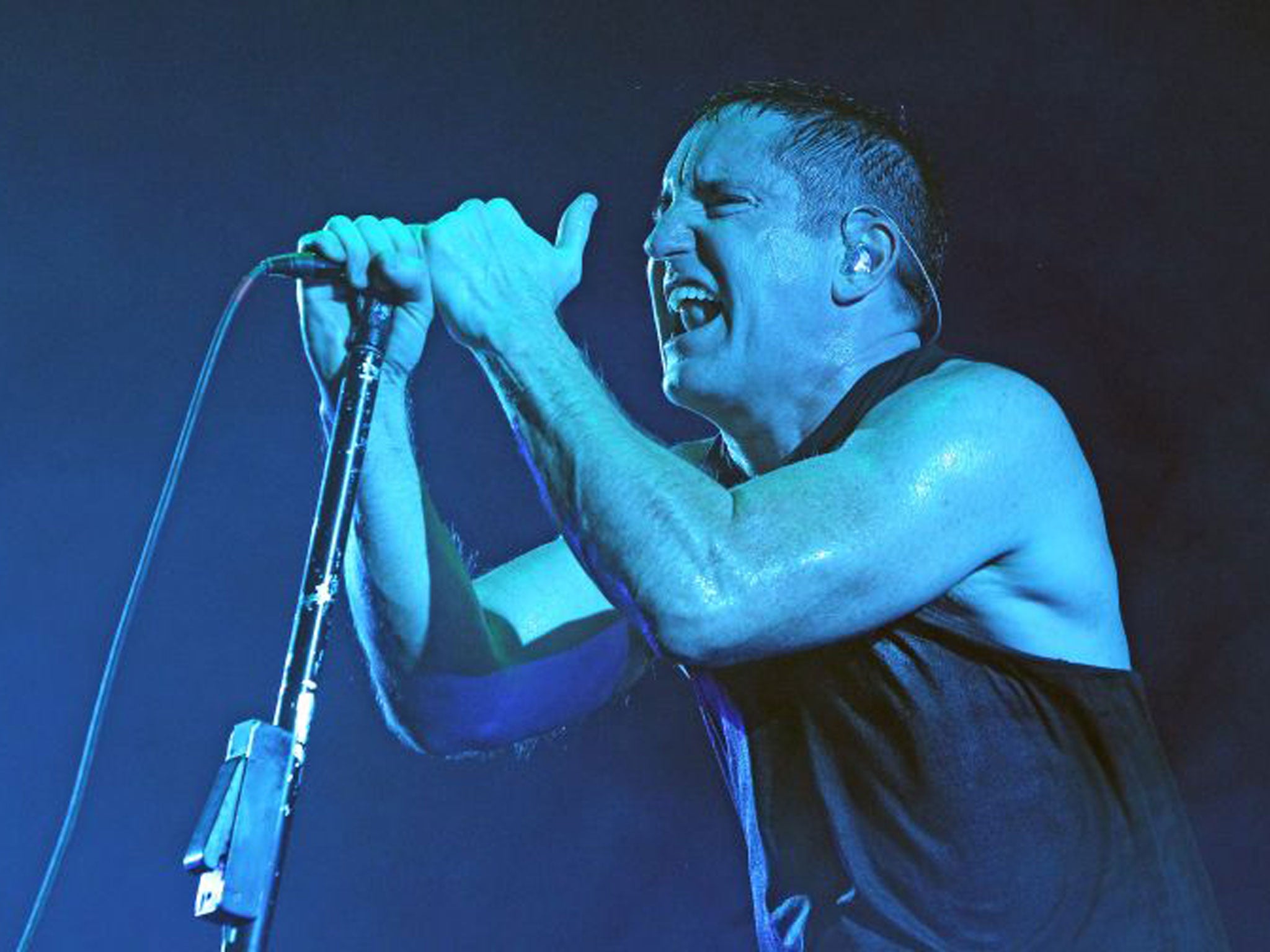

Troubled teenagers don’t listen to Nine Inch Nails in quite the same numbers that they used to, and yet the shootings continue. Reznor has for his part gone on to reinvent himself as Hollywood’s favourite goth, with his Oscar-winning soundtrack work for David Fincher. He continues to record as Nine Inch Nails (which now counts London composer Attitcus Ross as an equal member) and to put out interesting music.

Yet nothing he has done in the latter phase of his career comes close to the full metal alchemy of Pretty Hate Machine. It is a missive from a young man about to become successful beyond his wildest imaginings and who would nearly destroy himself along the way.

“I wrote about what was bothering me,” a fresh-faced Reznor said in 1990, as it all lay ahead. “What was in my head. People start thinking… ‘terrible love life, horrible traumatic childhood’. No. I feel certain ways about certain things. If someone can relate to it, that’s all I was hoping to do.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks