New Young Pony Club's Tahita Bulmer: 'How I discovered my father's glamorous past hanging out with Jimi Hendrix and The Rolling Stones'

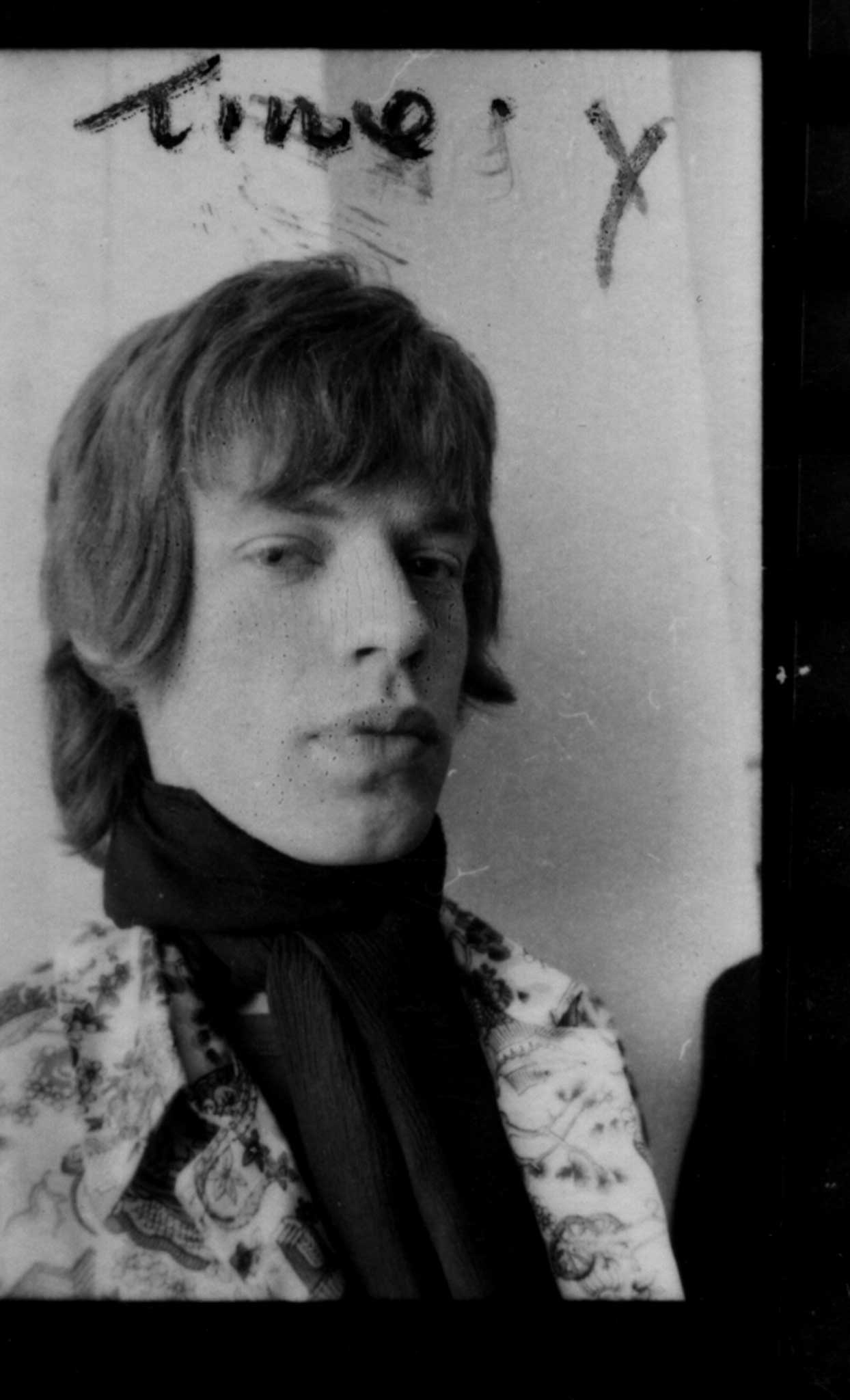

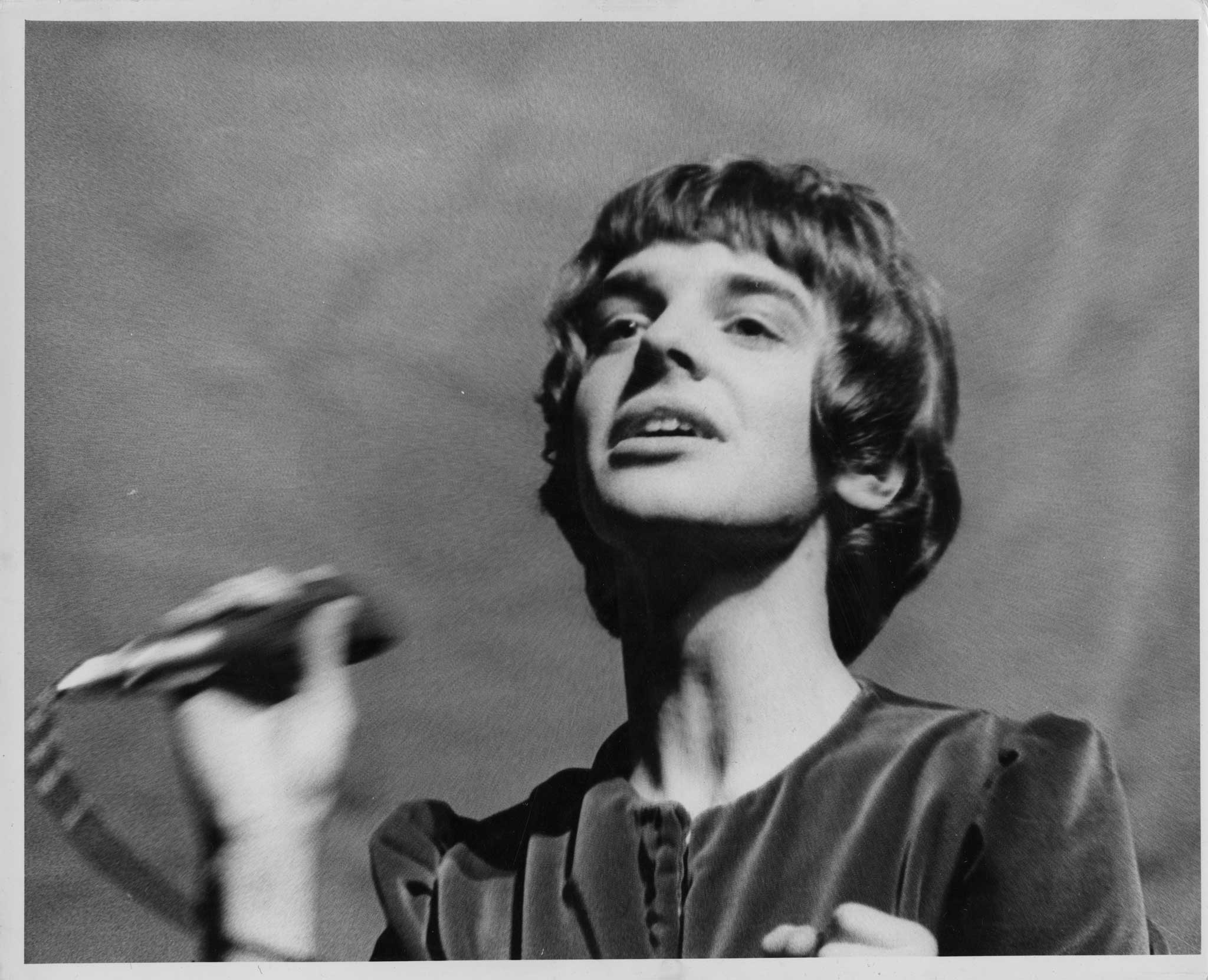

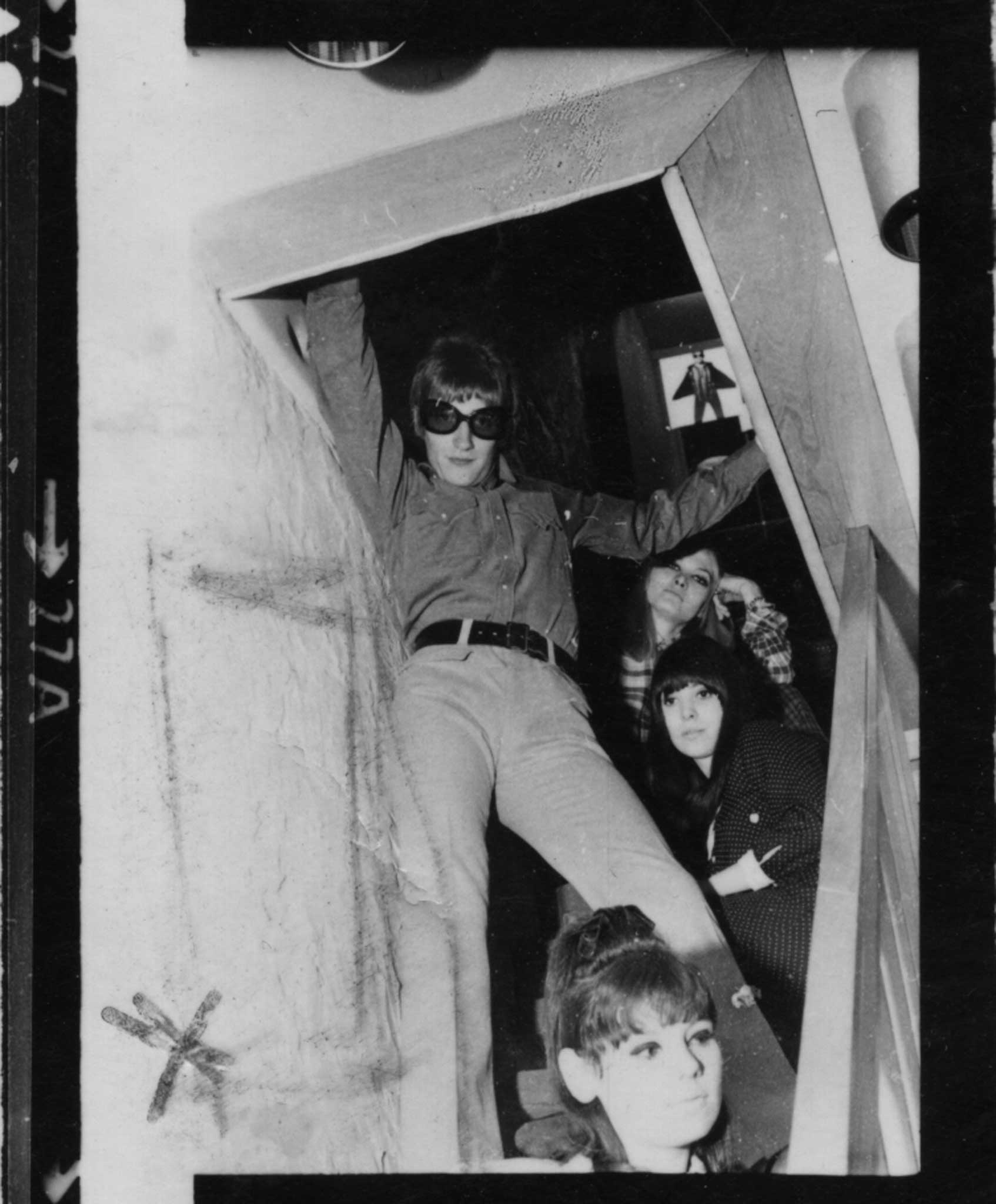

Bulmer's father, Rowan, was a commercial photographer in the 1960s and 1970s, friend to a myriad of the era's luminaries, and unofficial documenter for the rock and pop TV show Ready Steady Go! and the Marquee. One day in 2012 he turned up at her door with a cardboard box filled with contact sheets of previously unseen images of Swinging London...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the early Noughties, the idea of a music genre that melded the confrontational energy of punk and the louche cool of disco was the conversational equivalent of napalm. Mooting the idea provoked grimaces, barely concealed snorts of derision and loud coughing. But that didn't stop Andy Spence and I from continuing with our extremely enjoyable musical experiments in his box room. By the middle of 2005, we had christened ourselves New Young Pony Club and released the global cult hit 'Ice Cream' on tiny weeny dance label Tirk Recordings.

We were soon followed by a plethora of similar acts with whom we shared a glut of utterly meaningless genre definitions bestowed on us by confused journalists, who couldn't seem to get their heads around the idea that disco punk/new rave/tropical pop/new disco and electro pop were all essentially the same fusion of pop, disco, and alt guitar music with different ratios of archaic keyboard riffs vs live drum fills.

I'd been always been musical, studied opera in my teens and I'd been in several touring bands before, but New Young Pony Club was different. We were doing well in a manner that our parents understood, straight from the underground to the glossy mags falling out of the Sunday papers, which they could show their friends. A good deal of the success that followed, from 2005 to 2014, passed before our dazzled eyes like the ground seen from a rollercoaster with all of its breakneck turns, highs and lows.

My father, Rowan, had always been interested and supportive of my ambitions. As far as I knew, he had been a commercial photographer in the 1960s and 1970s, followed by a politically active phase while he lectured in fine art and photography through the 1980s and 1990s, until he met my stepmother and they started a business together importing porcelain lamp bases from China. He all but left photography behind, and his expansive collection of cameras and equipment was slowly diminished by a series of break-ins and thefts. He barely mentioned his past and certainly not his intense love of the blues and early R'n'B as a teenager, or the fact that it had led him to a more than cursory brush with the music industry.

At the Latitude Festival in 2007, we were pulled off stage after three songs by security as 5,000 people tried to barge their way into a k staging area meant for 1,000 and pushed the safety barricades down. My father had come from Bedfordshire to see us and professed himself disappointed at the truncated set. He sat down backstage with a cider and asked me if I was enjoying myself. I said yes and he smiled wryly and replied that I had better make sure that I did as the first 18 months of a band's ascent were the fun bit and everything would probably just become work after that. This struck me for months afterwards as a tremendously intuitive statement from a man who didn't work in the industry.

As the months and hangovers piled up there was more advice, all of it insightful and experienced; it was more like speaking to a veteran of the music industry than my father. "You're too much like me," he murmured, with subtle sphinx-like disapproval.

He worried that I wasn't interacting with the right people (I wasn't, they probably intimidated me) – people who could really move the band forward. He fretted that we had the wrong team around us (perhaps true). "Management is so important," he would sigh. And when I asked the importer of Chinese porcelain and Highland terrier enthusiast what he knew about the world of managing bands, he replied: "I managed Jeff Beck. I was terrible at it."

I prodded at him mercilessly whenever we met, conscious of the fact that there lurked a whole onion's worth of layers in this man, which he had previously hinted at but that I, with all the hubris of youth, had ignored as fatherly exaggeration. But I had vague memories of being a child surrounded by boxes of his photographs, housed in yellow Ilford photo boxes, a picture of Pete Townshend, Roger Daltrey and Scott Walker peeking tantalisingly out at me, proving me wrong, urging me forward with my questions.

Rowan loves London, knows it as intimately as anyone who ever completed the Knowledge. As a sullen teenager I would sit in the passenger seat of his clapped-out BMW while he pointed out the haunts of his youth; the house on the way to Chiswick, for instance, where Mick, Keith and Brian lived in one room and wrote the early Stones hits. "Did you know them?" I asked. "Oh yes," was the response, "Brian mainly. We discussed getting a flat together but it never happened." At the old family home in Chiswick, west London, where my dad grew up, Eric Clapton used to stay over when he didn't have enough money to get a taxi home after a trip to the R'n'B clubs in town. I asked my grandmother if she remembered Eric: "On the sofa, very polite."

We would stop at bookshops regularly on Saturdays during my teens so I could buy science-fiction novels and my father could rifle through the rock biogs, triumphantly appearing at my side to proclaim, "This one's mine!" finger jabbing at a grainy photograph of some rock icon at the Windsor Festival. "It doesn't say it's yours," I would mutter – eager to return to the interplanetary shoot-out in my hands. "No," he would say softly before sloping off to put the book away.

These recollections, coupled with my ongoing campaign to get the full story, culminated in Rowan turning up at my door in 2012 with a single cardboard box filled with contact sheets. Inside was a treasure trove of previously unseen images of Swinging London: Jimi Hendrix joking with his band, the Stones, Biba fashion shoots, doe-eyed beauties in heavy eyeliner dancing in front of Marquee livery, Paul McCartney playing the tuba, beautiful in black and white. I was gobsmacked. "Why has no one ever seen these?" I raged, always far better at fighting someone else's corner than my own. A shrug: "No one wants to see these old things."

It was at this point that my father's past began to finally unfold for me as a three-dimensional history. Rowan Bulmer, 1960s scenester, with a cavalcade of stunning model girlfriends, friend to a myriad of the era's luminaries, photographer of some renown, acting as the unofficial documenter for the rock and pop TV show Ready Steady Go! and the Marquee, meeting with Brian Epstein a few nights before he died to discuss taking photos of his new project. A someone, a mover and shaker. An artist in his own right, a painter and a sculptor, talented enough for the Indian artist FN Souza to wonder to his daughter Shelley, my father's most luminous paramour of the era, "Why has Rowan stopped painting?"

I couldn't believe he wasn't on a par with Gered Mankowitz in the pantheon of great rock photographers. Gered shared two shoots with Jimi Hendrix; whereas, as my father reported, "Jimi would always call me over and ask me to take his picture if we saw each other out. We got on." Where was the Rowan Bulmer Taschen coffee-table monolith? Where were his exhibitions, his renown for all of his wonderful work?

He was right there, in the thick of it. Countless music fans, cultural theorists and fashion mavens worship that time; they long to have been a part of it, to have had these experiences – and my father is the real deal, with endless tales, scandalous, amusing and always told in his humble way, apportioning no glory to himself, respectful even now of those friends who left him behind on the road to global superstardom more than 40 years ago. I feel I still don't know the half of it.

But it was never in his nature to push himself to the forefront of the scene, he was happy to record it and thrilled to see his friends succeed. But unlike his successors today, Instagramming their way to greatness, self-promotion is something of an anathema to him (as it is to me – in that we are very much alike). Perhaps that is the crux of all our woes, as mere talent does not automatically ensure entry into the VIP room of history. And – contrary to my former, rose-tinted understanding of the past – it seems it never did.

Since 2012, I have moved towards claiming a portion of the recognition that I feel my father's work deserves. I have consulted friends, journalists and photographers in an effort to find a way of putting him in the public eye; he should have his day in the sun. The task is made difficult by the fact that virtually all of his negatives (stored by his friend, John Gee, impresario of the Marquee club) disappeared when the Marquee was sold in 1988.

Despite the setbacks, he is still charmingly amazed at the interest his work now garners, and I think secretly rather pleased to have this opportunity again, at the age of 70. In some ways our roles have reversed: I have played out his missteps in my career in a way I know frustrates him and now here I am worrying about his career as he worried over mine. But there is something satisfying and empowering in coming to an understanding that his legacy is now my legacy in the same way that my legacy is also his. And we are closer than ever.

New Young Pony Club's single 'Sure as the Sun' is out now (wearenypc.com). Follow Tahita Bulmer on Twitter: @tahita29; Instagram: iamtahita

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments