New rave 10 years on: A joke or Britain's last great youth movement?

It was one of the most vilified pop music scenes ever, a byword for style over substance. Now, as Laura Martin looks back on those neon days with th key players, she wonders whether it was the last great youth movement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With any musical scene, you can usually find a dispute over its origins – and a decade on, exactly who created New Rave remains contested.

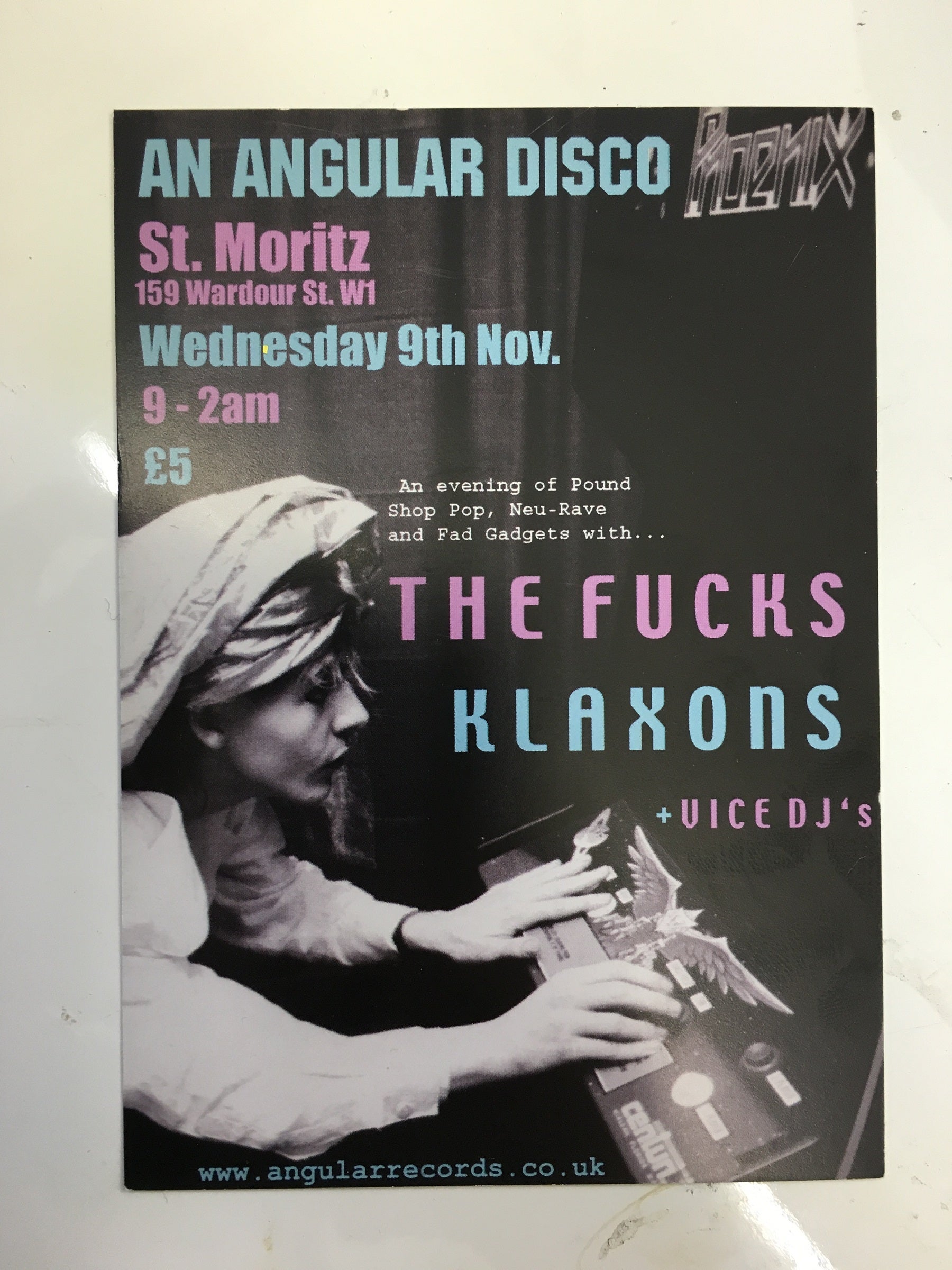

The most credible claimants to the title are Joe Daniel and Jamie Reynolds who, at the end of 2005 in a quiet south-east London computer room, coined the term “Neu Rave”, while putting together a flyer for Reynolds’ first show with his new band, Klaxons.

“We always used to think of names for scenes in a buzzy, sound-bitey way,” says Angular Records boss Daniel. “I thought of New Rave as a play on New Wave, and Jamie liked ‘Neu’ as a Krautrock reference, so we added it on.”

The other contender is the then NME editor Conor McNicholas, in whose magazine the less rarefied variants “New Rave” or “Nu Rave” first appeared in early 2006. “It’s hard to separate the myth from the reality, but as I remember, we invented the whole thing in the office,” he recalls.

That anyone should want to claim responsibility for New Rave might seem surprising, given how vilified the genre became. The net result of guitar bands channelling the Day-Glo hedonism of house music, it was mocked as a triumph of garish style over musical substance, a punchline for commentators keen to decry the cultural vapidity of the 21st century.

But while New Rave may have ended up as a joke, looking back now, it seems altogether more significant. Arguably, it’s one of the last times that music, nightlife, fashion and street culture all collided to create a British youth movement – albeit for an all-too-brief moment.

Far from being a cynical media invention, New Rave, to musicians such as Reynolds, was borne of a genuine creative impulse: “New Rave existed for me as an idea before it became a sound,” he says. His mission for Klaxons (with friends James Righton and Simon Taylor-Davis) was to fuse his childhood obsession with old 1990s rave – from DJ duo Ratpack to the era’s renowned Fantasia nights – with an indie band, then see how far they could take it.

They carried it a long way, not only selling 340,000 copies of their album Myths of The Near Future, and winning the 2007 Mercury Music Prize, but making the industry go wild for a host of similar bands including New Young Pony Club, Shitdisco, Late of The Pier, Does It Offend You, Yeah? and Hadouken!.

While varying in musical quality, they were united by a euphoric flamboyance that helped to finally shift indie music away from the kind of blokey post-Britpop bravado that had dominated for so long. “At the beginning, it was an amazing moment to be a musician, it felt like the tyranny of four men in leather jackets was coming to an end,” says Tahita Bulmer, frontwoman of New Young Pony Club who were nominated alongside Klaxons for the 2007 Mercury.

Brazilian group CSS, known for their charismatic, oft-sequinned frontwoman Lovefoxx, were another key group. “Performing at that time with all these other bands we felt like there was really something special happening. It brought people together, it was DIY, messy and funny,” says the singer, aka Luísa Hanae Matsushita.

New Rave dovetailed with a burst of creativity in London nightlife: inspired by New York’s queer electro-clash scene, which combined disco and punk with avant-garde fashions, a whole host of club nights exploring the creative and humorous side of nightlife emerged in the East End, including Boombox, Antisocial, Girlcore, Trailer Trash, Wet Yourself and All You Can Eat. The latter was launched by promoters Jim Warboy and Fayann Smith in January 2006 and was described by i-D magazine as “this decade’s Taboo club”.

Smith says: “We wanted to give this new emerging energy a flashpoint, where it could live and breath.” It also allowed for a new kind of night. “We were making music for DJs to play at club nights and it was that crossover that united the bands at that time,” says Reynolds.

As live gigs and DJs morphed together in one party, the natural home for these events became warehouse parties, where bands would be supported by record-spinners such as Simian Mobile Disco, Justice, Erol Alkan, 2ManyDJs, Hannah Holland and Rory Phillips.

That New Rave arrived just as social media was blossoming also allowed it to spread its wings in a new way. While harnessing Myspace to build connections with clubbers, All You Can Eat also launched their own TV website and streamed their own fashion and music shows. In a world where Youtube had only just launched, Smith and Warboy were approached by MTV to help develop its online channels.

The creators of Skins also recced their nights to use as a blueprint for raves in the E4 teen show, which launched in 2007 and brought the neon-soaked New Rave aesthetic to a mass teenage audience.

New Rave’s place in fashion was cemented by then-unknown designer Henry Holland, a regular at Boombox, which inspired him to launch his range of Fashion Groupie T-shirts in September 2006 – neon slogans shouting out “Get yer freak on, Giles Deacon” or “Cause me pain, Hedi Slimane”.

“It felt like London was in the midst of something really amazing,” Holland says. “The fashion at these parties was moving towards the ridiculous – it was basically Sue Pollard meets Timmy Mallet, they were like style icons to us.” Glitter and UV-paint were the least of it.

A plant pot as a hat? Sure. A carton of Rubicon juice turned into a necklace? Why the hell not. Holland aside, other designers such as Gareth Pugh, Christopher Kane, Jeremy Scott and Carri Munden caught the New Rave vibes and started featuring it in their shows too.

In turn, this youthful outburst finally switched the world’s fashion gaze on to London Fashion Week, says Holland. “I remember when I first started showing in 2006, it was very rare that the Americans would come to London, because it was their week off until Paris or Milan.

That totally changed then; there was such a buzz around London, centred around its street and club culture. I don’t think it’s done that since. It feels like New Rave is the last time that happened.”

Whether inventors or merely champions, NME were cheerleaders of the new genre – with sales dropping and their role as musical gatekeepers in jeopardy thanks to MySpace, they needed something they could call their own.

“When the Klaxons turned up and were so obviously going to be a big cultural thing, journalists did what journalists do and looked around for another few bands that felt vaguely the same and stuck a genre on them,” says McNicholas.

But just as soon as the scene blew up, the backlash started. By the summer of 2007, every high-street retailer was stocking Day-Glo hoodies, coloured skinny jeans and lensless glasses. Brands were desperate to sell New Rave back to young consumers.

Garish as it was, the look dated very quickly and the scene attracted increasing scorn: a “piss-poor ... supposed youthquake” was how The Guardian classified it in an article entitled “New Rave? Old rubbish.” “As the name caught on, the credibility in the scene went down the drain,” says Bulmer. “Suddenly we weren’t to be taken seriously. It became an albatross preventing us from being seen to evolve.”

New Young Pony Club rebranded as NYPC, genre-mates Hadouken! went monochrome and Klaxons swerved into psychedelia. But the brutal reality was that they were indelibly associated with a toxic brand. “Nobody who was associated with that scene was able to create a second album that anyone gave a shit about,” says McNicholas.

The party was over. Smith hosted the last All You Can Eat at the end of 2007: “When it went mainstream, people wanted to kill it and suffocate it. I don’t know what bothered them so much about it – people hated east London and everything portrayed in shows like Nathan Barley. It just didn’t feel like it was conductive atmosphere to keep doing it.”

Few mourned its passing at the time – but with hindsight, it may just have represented the death of something bigger than itself.

If New Rave had a short shelf life, it’s even harder now for youth tribes to thrive and survive – trend-forecasters scour the internet to sell fledgling cultures to big brands to then hawk back to anyone not quick enough not to catch it at its infancy. “I don’t think we have these big explosions of subculture anymore,” says James Smith, former frontman of Hadouken!.

“There’s Grime, but it’s been around for a while and will always be there. I’ve been waiting for something like New Rave to come along in the indie scene again, but it hasn’t.”

Though, given the current rate of cultural recycling, you should probably get those glowsticks, plant pots and juice cartons ready for the New Rave Revival of 2026.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments