Music is good for our health, so why are musicians suffering so much?

From Zayn Malik and Lady Gaga to Charli XCX and Stormzy, some of the world's biggest artists have struggled with mental health. Roisin O'Connor wants to know what the industry is doing to help

“Music was my refuge,” the writer Maya Angelou once said. “I could crawl into the space between the notes and curl my back to loneliness.”

It’s a neat way of summing up the powerful impact music can have on our mental state. Indeed, its ability to soothe our troubled minds has been explored for centuries.

Greek physicians used instruments such as lyres and zithers to help heal their patients, while Aristotle believed that flute music could arouse strong emotions and “purify the soul”. In Italy, celebrated castrato singer Farinelli was employed at the Spanish Court for 10 years, where he sang to King Philip V after his wife, Queen Elisabetta Farnese, suggested the musician’s voice might have the power to cure his depression. When President Nixon had trouble sleeping, he apparently liked to play Rachmaninov’s piano concertos at “ear-splitting volume”.

In the 21st century, research suggests there is a connection between music and its effect on various illnesses. Studies have shown it to slow heart rate, lower blood pressure, and reduce levels of stress hormones. Research conducted in 2005 by the University of Windsor in Canada, meanwhile, showed that music could improve cognitive function.

And yet the health of many artists and other music professionals is dire.

It’s easy to understand how sudden fame, or a lifestyle built around creating music and live shows, could lead to drug and alcohol abuse, or even cause serious health issues. Lady Gaga told The Mirror in 2016 that she has blocked out the memory of rising to fame: “It’s like I’m traumatised,” she said. “I needed time to recalibrate my soul.”

Zayn Malik, who overnight became one of the most talked-about people on the planet after One Direction came second on the 2010 series of The X Factor, has anxiety so severe that it has forced him to cancel several solo tours. Two years ago, he wrote a first-person account in his book, Zayn, which addressed the multiple issues that fame had either caused or exacerbated.

“When I was in One Direction, my anxiety issues were huge, but within the safety net of the band, they were at least manageable,” he said. “As a solo performer, I felt much more exposed, and the psychological stress of performing had just got to be too much for me to handle – at that moment, at least.”

Even just the act of trying to break into the industry can be so stressful that it can have a massive impact on an artist’s health. Today, Nicki Minaj is regarded as one of the best rappers around, but in 2011, she recalled to Cosmopolitan how she had suffered from suicidal thoughts after being turned away time and time again.

“I kept having doors slammed in my face,” she said. “I felt like nothing was working. I had moved out on my own, and here I was thinking I’d have to go home. It was just one dead end after another. At one point, I was like, ‘What would happen if I just didn’t wake up?’ That’s how I felt.”

Her experience is all too common. “The industry is brutally competitive and only a very few make it to a successful career,” says Peter Leigh, CEO of the charity Key Changes, which provides music engagement and recovery services in hospitals and communities for young people and adults affected by depression, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and other mental health disorders.

“Some of the triggering factors of the problems we see in the music community include self doubt and stress brought about by rejection and failure, poor decision making based on bad advice and exploitation. The fact that record sales peak immediately after an artist’s death is an illustration of the often callous power of the media and the market.”

Serious discussion about how we deal with mental health in the music industry was sparked by a detailed survey published by Help Musicians, the leading independent UK music charity, in 2014. It was found that 60 per cent of musicians had struggled with their mental health, whereas the overall figure in the UK is 25 per cent. In that same study, 68 per cent said they struggled with loneliness or separation from family and friends, and a staggering 75 per cent of musicians said they had experienced performance anxiety.

Fans may wonder what musicians are talking about when they discuss the pressures of live shows. They look like they’re having fun – what’s the problem? Yet scientific evidence shows how the “fight or flight” response is very likely to kick in during a high-pressure situation such as a gig, where a singer is positioned facing hundreds or even thousands of people who are staring right at them. For some, this can lead to a better performance due to the heightened state of awareness and adrenaline rush it causes. For others, it can cause panic attacks or even memory loss, which can lead to long-term anxiety about live shows.

“It’s nothing to do with age or inexperience,” Aaron Williamon, professor of performance science at the Royal College of Music, told The Guardian in 2015. “No matter how highly skilled a person is, the body’s pre-programmed stress responses mean they can enter a different physical state and sometimes even a different psychological state.”

Even in the past few weeks, musicians have shared stories about their issues with mental health. Ben Gregory, frontman of the British indie band Blaenavon, revealed last week that he suffered a stress-related breakdown after “an incredibly hectic and difficult 2017”, and was admitted to hospital before Christmas that year.

“I’m proud and thankful for being able to overcome it,” Gregory said in a statement on Twitter, where he thanked his bandmates and label for supporting him during the difficult period. “I’m now the happiest I’ve been in years: not drinking, exercising, feeling healthy and positive about the future.”

Last year, Demi Lovato was admitted to hospital for a suspected drug overdose but has since been in recovery and often shares updates on her wellbeing with fans. Even before then, Lovato – who has bipolar disorder – had been a huge advocate for mental health care and has even featured free mental health counselling sessions at her concerts.

“There’s a new breed of pop artists such as Lovato and Years & Years frontman Olly Alexander who aren’t afraid of talking about mental health,” says Leigh. “Ironically the most powerful impact on mental health awareness within music tends to come after the death of an artist – such as Avicii, Prince, George Michael, etc. One of the most long-lasting legacies has been the Amy Winehouse Foundation set up by Amy’s family which has created many amazing opportunities for young people – we’re really grateful for their gift of a recording studio for our charity that’s helped hundreds of artists achieve their goal of making great music with industry professionals.”

Charli XCX is one of several high-profile artists who have been open about their struggles with anxiety. Back in 2014, in an interview with The Guardian, she spoke about how panic would arise when she was writing with an artist she hadn’t worked with before. Earlier this month, she summed up the exasperation that comes with such a debilitating issue, tweeting: “F*** anxiety f*** anxiety f*** anxiety f***.”

She followed this up with a slightly more nuanced comment: “Anxiety always hits me when I least expect it and it’s so explosive and really just flips my world inside out. I know loads of people can relate. I think it’s good to talk about / normalise / be honest.”

As well as artists who speak publicly about these issues, there are a number who address it via their music. In 2017, Logic released his Grammy-nominated collaboration with Alessia Cara and Khalid, “1-800-273-8255” (the phone number for the American national Suicide Prevention Lifeline), which addresses feelings of severe depression and suicidal thoughts.

According to the NSPL, in the three weeks that followed the track’s release, calls to their helpline rose by 27 per cent, while website visits jumped from 300,000 to 400,000 over the following months.

Maggie Rogers distils her personal experiences of anxiety into her new album Heard it in a Past Life, with the song “Back in My Body” describing the moment she “almost ran away” in Paris while on her European tour in 2017.

“I was doing so much press,” she told The Independent in a recent interview. “It made me miserable. I remember I was in the middle of a video session in Paris and I walked outside to have a cigarette. I thought, ‘I have enough money to buy a plane ticket’… before people really realised where I went.”

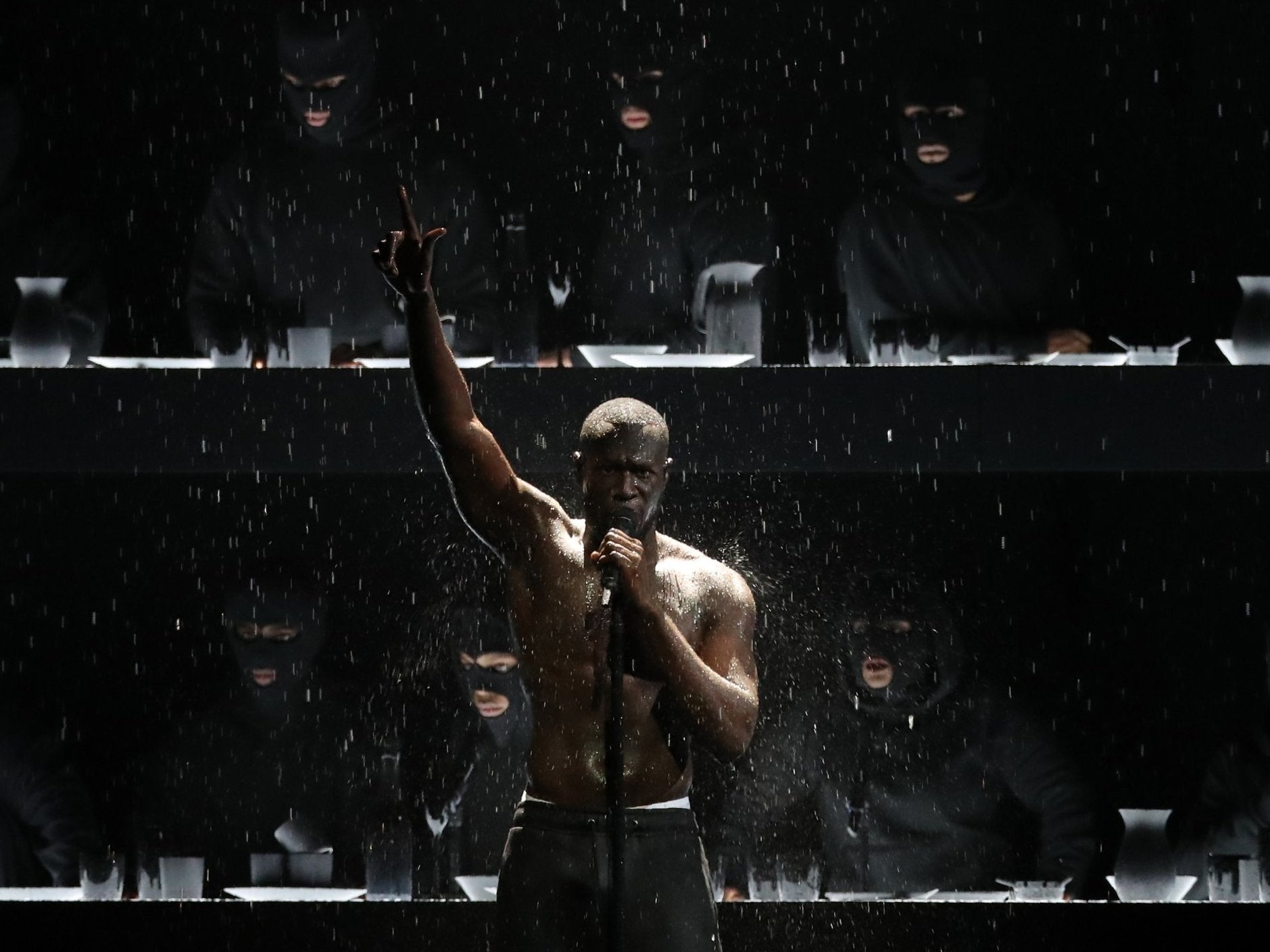

And on his critically adored album Gang Signs and Prayer, grime MC Stormzy showed courage with the track “Lay Me Bare”, which features the lyrics: “Like man’a get low sometimes, so low sometimes / Airplane mode on my phone sometimes / Sitting in my house with tears on my face / Can’t answer the door to my bro sometimes.”

In an interview with Channel 4, the rapper reflected: “If there’s anyone out there going through that, I think that for them to see that I went through it would help.”

While witnessing one of your heroes in the same boat as you can indeed prove beneficial, there is also a level of responsibility that must be put on labels, management and touring companies to ensure the musicians they are working with are being supported.

In 2016, Sony Music UK became the first music company to partner with a mental health charity (MIND), and has made several commitments to supporting its staff, from offering them opportunities to take part in “mental health first aid” training or office activities in the office such as yoga and body acceptance discussions, to hosting a “Mental Health & Music” panel discussion at its company HQ in London.

Help Musicians UK has partnered with Independent Venue Week 2019 (IVW) to launch the “Live Music, Help Musicians” campaign, taking place at over 230 grassroots music venues around the UK later this month. Inspired by research highlighting a serious need for better mental health support in the live music community, the charity will equip venue management and staff with “healthy venue packs” that include hearing protection, along with information and signposting on support for artists who may be struggling.

“HMUK wants a world where musicians thrive, and the foundation of many musicians’ emergence into the industry is through the grassroots music venue circuit,” says Joe Hastings, head of the charity’s health and welfare department. “It is therefore fundamental to HMUK that grassroots venues and the musicians we support thrive. We aim to not only support artists and upskill the sector during and beyond IVW, but also cultivate an ongoing nationwide conversation around the health and welfare needs of artists on tour.”

“The ‘Live Music, Help Musicians’ campaign is one of the most significant developments in mental health for the sector,” adds IVW founder Sybil Bell. “With the continued growth of venues who have joined the IVW family all around the country, being able to work with HMUK and our venue partners means collectively, we can start to have a real and meaningful impact for artists and those around them at the venues, during their touring period and beyond. By continuing the work beyond IVW, we can keep the support going across the year when it’s needed.”

The way mental health is covered by the media is also crucial. Many may argue that we have moved on from the days where tabloid journalists and paparazzi salivated over images of Britney Spears shaving her head, or beating a photographer with an umbrella, but how far have we come, really? Just last year, with Lovato’s issues brought painfully into the public view, the feeding frenzy from certain parts of the media was often difficult to watch.

Will Gore, who worked in press regulation for a decade before moving into journalism (he is currently executive editor at The Independent), suggests that the “rock and roll” narrative beloved by so many tabloid journalists (and media consumers) “perpetuates a myth that musicians somehow ought to be capable of superhuman fortitude – until, that is, they burn out”.

He adds: “Yet the cases of burn-out, mental breakdown and even death only seem to add to the superficial allure of lives lived fast and dangerously. It’s not hard to suspect that this perception suits the industry down to the ground when it comes to marketing and sales – but it is hardly likely to help vulnerable stars who strive to meet such unrealistic expectations.”

Leigh agrees: “There is a danger that the complexity of the subject matter is lost in some of the easier-to-tell and more easily understood stories about depression and anxiety than, say, schizophrenia and personality disorders.

“The system itself (hospitals and services) is still largely hidden from public view in out-of-the-way locations and anonymous looking buildings, and there’s still very little awareness around what it means to be sectioned under the Mental Health Act, detained in hospital or forcibly medicated.”

Arguably one of the closest examples we have to the clichéd definition of a rock and roll frontman in modern music is The 1975’s Matty Healy, who is often presented in interviews as a kind of romantic, tortured genius. Healy himself has made efforts to clarify that he is aware “this isn’t real” while at the same time being open about his issues with drug addiction.

“The manicness seems to resonate with people, because they know how it feels,” he said in an interview with Billboard, referring to his honesty about feelings of anxiety – both in his music and in the public eye.

“I’m so aware of the vocabulary of rock’n’roll, and what’s tired,” he added. “It’s difficult because everything’s so postmodern and self-referential and hyperaware of everything being bulls**t. As I grow as an artist, I just want to be sincere.”

Key Changes is working with musicians who are experiencing mental health problems in order to support their recovery, via songwriting, production and recording sessions, as well as live performances, marketing promotion and business advice. Support is also provided for artists to access its psychological therapies, and help with problems like addiction and debt.

“We’re linking the health and social care sector with the music industry to provide access to culturally relevant treatment not available elsewhere in the NHS,” says Leigh. ”And we’re addressing the music industry’s poor record on supporting artists who are struggling with their mental health.”

“Music performs a vital role in improving health and wellbeing," says UK Music CEO Michael Dugher. It’s for everyone in the industry to promote the help that is out there for the many people who will need it – and to work across the industry and with policymakers to improve that support and to help lift the stigma”.

If you have been affected by any issues mentioned in this article, you can contact The Samaritans for free on 116 123 or any of the following mental health organisations:

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks