The secret humiliation that really ended the career of Maria Callas

She was the opera diva who had a tumultuous and tragic private life, but while this added to her myth, something else entirely would derail her career as one of the greatest singers of all time – as Meghan Lloyd Davies explains

Her talent saw her transcend poverty to achieve global fame, her work ethic made her the greatest opera star the world had ever seen, and her style made her an icon. Add it all together and it becomes clear how Maria Callas wanted history to remember her. “I am a woman and a serious artist,” the great singer once said. “And I would like so to be judged.”

Almost 50 years on from her death, however, the public perception of Callas all too often skews towards one persona: that of the tortured female star. From demanding diva to heartbroken lover who gave it all up for a man, the iconography of Callas’s art is indelibly linked to – and often overshadowed by – a private life in which tragedy, ambition, talent and melodrama collided.

Biographer Lyndsy Spence, author of Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas, says: “Maria Callas lived her life trying to meet the demands of the public, who were often unforgiving in their criticism, especially when Maria, the woman, could not channel the supernatural power of Callas, the artist.”

Such is her continued grip on the popular imagination that Spotify, where her music has been streamed more than 7 billion times, marked the centenary of her birth, and today, Maria, the Netflix biopic starring Angelina Jolie that depicts the singer’s final days, is released.

But separating the woman from the world-famous soprano known as “La Divina” – the divine one – is something even Callas herself found hard.

“It’s a very terrible thing to be Maria Callas, because it’s a question of trying to understand something you can never really understand,” she once said to friend and music critic John Ardoin.

Callas was born in 1923 to Greek parents who’d emigrated to New York; her mother, Litsa, had lost a son, and was so convinced that her new baby would be another boy that she was unable to look at her newborn daughter for four days. It marked the start of a troubled relationship that left Callas feeling constantly second best to her older sister Jackie.

When it became clear that Maria had a real talent for singing, her mother “wanted to reap the benefits of [her] voice but she also wanted to control her”, Daisy Goodwin, the author of Diva, explains in the new BBC documentary Maria Callas: The Final Act.

Callas, however, soon discovered that “when I sang, I was really loved”. At the age of 13, she left New York for Athens with her mother and sister after her parents’ marriage broke down. The trio lived in poverty. Within a few years, Nazi forces had occupied Greece, and Litsa is said to have pushed Callas and her sister to form relationships with occupying troops in return for money and food. Callas refused, but her relationship with her mother was so troubled, she eventually cut off all contact with her.

The seeds of Callas’s determination and ambition are peppered throughout the story of her early life.

She started training at the Greek National Conservatoire after lying about her age in order to be admitted. At 18, she made her operatic debut; she performed 56 times at the Greek National Opera before returning to New York in 1945. There, she worked three jobs to support herself, but she turned down a “beginner’s contract” with the Met.

Fate intervened when her talent was spotted, and Callas was invited to Verona, where she debuted in 1947. She quickly garnered attention for both her incredibly versatile voice and her great acting talent. Relentlessly disciplined, Callas crossed vocal boundaries and threw out the rulebook that governed how opera singers usually performed. The Italian public was entranced. Directors including Franco Zeffirelli and Luchino Visconti mounted special productions to showcase her.

“I will always be as difficult as necessary to achieve the best,” she said.

But Callas’s personal story was also increasingly linked to her work. Perhaps its most physical manifestation was her dramatic weight loss in the early 1950s. Shedding 70lbs, she transformed into the iconic figure she’s still remembered as today: pencil-thin, red-lipped, and often accompanied by one of her beloved poodles.

I thought when I met a man I loved that I didn’t need to sing

By the mid-1950s, Callas was world-famous, appearing at all the great opera houses including Covent Garden, La Scala and the Met. But controversy also began to haunt her as the image of the “difficult” female star was perpetuated. A Time magazine cover story in 1956 talked about her “ruthless ferocity” and “insatiable thirst for personal acclaim”. A string of incidents hit the headlines: a very public falling out with La Scala in 1957, uproar when she pulled out halfway through a performance in Rome the following year, and the termination of her contract with the Met months later.

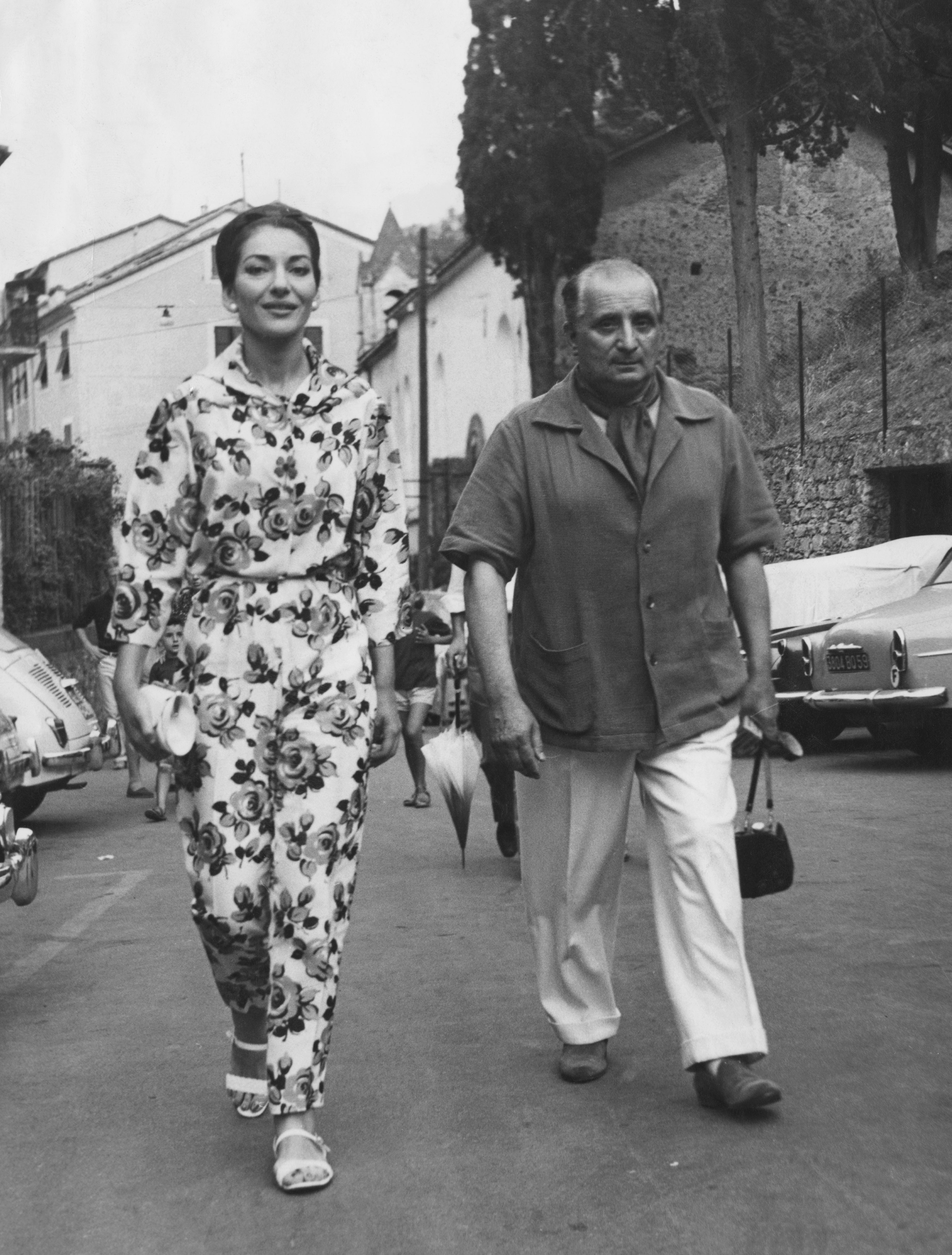

Her personal life, too, added to the myth. In 1949, Callas had married the wealthy Italian industrialist Giovanni Battista Meneghini, who became her agent. But a fateful meeting with Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis would change the course of her life. In 1959, Callas and Meneghini were invited to cruise the Mediterranean on Onassis’s luxurious yacht. By the end of the year, both Callas and Onassis had left their respective spouses.

The public was enraptured at the pairing of the older, ultra-rich tycoon and the beautiful, younger opera star.

Callas retreated more and more from the stage as she was plunged into the world of high society, spending time with celebrities including Princess Grace of Monaco, Marlene Dietrich, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. As her career waned, some claimed that Onassis was the cause. Others believed that her weight loss had permanently affected her voice. While most sopranos peak in their forties, Callas made her final operatic performance at Covent Garden in 1965, aged just 41. The relationship with Onassis spiralled. She had two miscarriages, was humiliated by his affairs, and Spence recounts Onassis cruelly taunting her for the “whistle in your throat that no longer works”.

By 1968, the affair had ended, and the world was entranced once again as Onassis married Jackie Kennedy, leaving Callas heartbroken. The myth that a man was responsible for the demise of her career was sealed – an idea that Callas seemed actively to fuel at times.

Speaking to Barbara Walters in 1974, after a comeback tour had been savaged by critics as a “travesty of former greatness”, Callas said: “I thought when I met a man I loved that I didn’t need to sing. As a woman, the most important thing is to have a man of her own and make him happy.”

The new BBC documentary, however, claims that both Callas’s weight loss and her relationship with Onassis were mere smokescreens. The real reason Callas withdrew from performing is that she knew her voice, her most precious tool, was deteriorating far earlier than it should. Her early vocal training had baked in defects that had made her sound unique but had also prematurely aged her voice, creating imperfections she knew were not acceptable.

Callas retreated to Paris, where she started to take Mandrax – a highly addictive sedative – and her exact state of mind in the months and years before her death can only be speculated upon. She is known to have lived largely in isolation prior to her death from a heart attack, aged 53, in 1977.

What we can, however, be sure of is that her legacy lives on. And Callas believed, rightly, that her creative and cultural impact far eclipsed her tumultuous private life.

“You are born an artist or you are not,” she once said. “And you stay an artist, even if your voice is less of a firework. The artist is always there.”

‘Maria Callas: The Final Act’ is available on BBC iPlayer; ‘Maria’ is in cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks