Madonna and me: my life as a material girl

The Queen of Pop sent a generation of Voguers into panic this week after a stay in intensive care forced her to postpone her tour. Helen Brown charts a life growing up with Madonna, from mimicking the ‘Like a Prayer’ choir as a schoolgirl in Leicester Cathedral to dancing in gay bars and deciding whether to age (dis)gracefully

Is Madonna dead?” My phone’s been pinging with this question for 48 hours. I have to keep reminding my friends that although I’ve often written about my “relationship” with Madonna over the past 20 years, I don’t actually know her. I’m just a fan. I don’t know any more than they do about the “serious bacterial infection” that meant she was found unresponsive at her New York flat and admitted to the ICU on Saturday. And, like other fans around the world, I was knocked weirdly off-kilter by the news.

In comparison to so many pop stars, whose celebrity lifestyles see them tumbling into addiction and illness, Madonna is famously health conscious. Superfit. I stood a few metres from her at the launch of her first children’s book and, though she was tiny and dressed in a floral summer frock, her arm muscles were so intensely yoga-toned that she looked like a superhero undercover at a village fete. After a short stay in hospital, the 64-year-old pop icon was reported to be back at home on Thursday and, according to her longtime manager Guy Oseary, “a full recovery is expected”. But it’s clearly been serious enough for her to postpone the career-showcasing “Celebration” tour, which was due to kick off in Vancouver in mid-July and reach a four-night run at London’s O2 Arena in October.

Although none of my friends had bought tickets for the tour before Madonna’s medical emergency, once the world knew she was out of danger my phone started to fill with a different type of text: “We should go, right?” “I know the swanky tix are £1,307 but we could get the £47 ones?” “Come on, girls! One last big Madge boogie? Can we dig out the crosses and lace ribbons?!” And ohhhh, there came the whack of what Madonna has meant to me and so many of Gen X’s girls and LGBTQ+ers. The muscle memory of first wrapping those trademark ribbons around my wrists, piling my hair on top of my head and pouting into the mirror to “Get into the Groove”. Hoping to channel just a little of the singer’s electric, autonomous cool. The push/pull gaze that said “come on” and then “I dare you”.

If you dressed up as Madonna, as a kid in the Eighties, you had to be creative. Accessories had to be crafted; we didn’t have Claire’s back then. I swiped my lace from my mum’s sewing cupboard, cut some black netting for my hair from the underskirt of a homemade Halloween costume. In the afternoon darkness of our suburban garage, I rummaged through my dad’s extendable metal toolbox and found some black rubbery stuff to knot into bracelets. I still have no idea what some of them were – bits of old fan belt? Puncture repair stuff? – or whether they were missed (sorry, dad). But they smelled rather thrillingly of oil and rust and rebellion. Kids today – my kids – don’t remember that before she was a global pop brand, Madonna was a punk. A DIY diva. She made her art of scavenged sounds, skip-dived and shoplifted ideas, all thrown together in clashing combinations then discarded as she moved on to the next shiny thing. Frida Kahlo and Monroe, Basquiat and the gay disco…

As an uncool kid – content with the records in my parents’ collection until high school – I was a little late to Madonna. But after I’d humiliated myself, aged 10, by telling a more popular and culturally aware girl that my favourite album was The Beatles’ Abbey Road and I’d never heard of her favourite by Five Star (surely I now get the last laugh) my dad went down to the high street and bought me a cherry red cassette player and a selection of “current” albums recommended by the bloke on the Woolworths counter. It was 1986 so I got Wham!, Bananarama, A-ha… and True Blue by Madonna. THIS was the one.

Critics can be sniffy about Madonna’s voice, knocking it as thin or girlish. And it’s true she’s no Nina Simone. But boy, can she sell a story! That’s what hooked me into True Blue. I was lost in the melodrama of “Papa Don’t Preach” with its formal string arrangement playing off against the singer’s snarled determination to stand by an unplanned teen pregnancy. Madonna sounded like the most worldly girl in class. It wasn’t until later – after she’d published her infamous SEX book – that I’d read interviews in which she said she’d moved to New York from Pontiac, Michigan at 17 because her dad wouldn’t allow her to date local boys. “I never saw naked bodies when I was a kid,” she said. “Gosh, when I was seventeen, I hadn’t seen a penis! I was shocked when I saw my first one, I thought it was really gross.”

My child self also connected with the deep pain that clearly welled beneath those bubble gum beats. My favourite song on the album was the heartbreak odyssey of “Live to Tell”. Every time I was in trouble at home for getting ink stains on my uniform (like Madonna I daydreamed in class and my pen would roll into my sleeve), I’d run upstairs and play the song on repeat, emoting plaintively into my hairbrush, imagine packing a bag and SHOWING THEM ALL, before the self-pitying acknowledgement: “If I ran away/ I’d never have the strength to go very far/ How would they hear the beating of my heaaaaaarrrt?” I didn’t know it then. There was no internet and I hadn’t discovered music journalism.

Like one of my other childhood heroes, Dolly Parton, Madonna can have the air of girl in a woman’s body, dressing herself up like a Barbie, acting out bedroom fantasies of fame, sex, power and money. Never thinking it’s time to stop wanting and grow up

But the much deeper pain to which I was hitching my childish dramas came from Madonna’s grief: her mother died when she was just 12 years old. I think trauma pins some parts of the soul. I’ve always thought some part of Madonna is eternally 12, and so kids of my vintage connected with her as a peer with a platform on some level. Like one of my other childhood heroes, Dolly Parton (who modelled her lifelong sound and image on her childhood ideas of sexiness and glamour) Madonna can have the air of a girl in a woman’s body, dressing herself up like a Barbie, acting out bedroom fantasies of fame, sex, power and money. Never thinking it’s time to stop wanting and grow up.

That childhood bereavement – later echoed by the deaths of her gay friends during the AIDS epidemic – left Madonna raw on one side and burned on the other. Aware that life was fragile, she was determined to seize every opportunity. Because the worst had already happened, she became fearless and perhaps a little detached. She took what she wanted from friends, lovers, collaborators and moved on. No hard feelings. In an age when women were valued for their people-pleasing, this was revolutionary. Having watched her mother – who filled their home with Catholic statues of saints and solemn Virgin Marys – die so young despite her prayers, Madonna developed a keen eye for BS and social hypocrisy.

“It was just the rules,” she said. “There were so many rules, and I just never could figure out what they all were. If somebody had given me an answer, I wouldn’t have been so rebellious. ‘You can’t wear make-up, you can’t cut your hair.’ You can’t, you can’t, you can’t.” So she did and she did and she did.

After True Blue, I saved my pocket money and bought her first two albums: Madonna (1983) and Like a Virgin (1984). In 1989 I was 14, at a friend’s house after school when I first saw the video for Like a Prayer. I was in my school choir – we sang daily in Leicester Cathedral – and so the vocal swell and iconoclastic imagery was thrilling. I was an atheist but deeply romanced by much of the religious music I sang, getting shivers as my voice joined the others floating across the ancient pews as we pleaded with Christ to have mercy.

My friend, on the other hand, came from a devout Catholic family. So the first big philosophical debate we all had was whether we should copy Madge and add some crucifixes to our jewellery boxes. It felt like a massive ethical dilemma. The woman my parents dismissed as a “silly pop singer” sparked the first really big, divisive moral dilemma we’d faced as a group. I decided I shouldn’t wear crucifixes because I wasn’t a Christian. My Christian friends opted out because they were. In the end, I remember two of us compromising on some silver crosses with equal-length prongs so they “evoked” the crucifix without copying its precise dimensions. We were so pleased with a solution that would have made Madonna laugh.

Although my male friends and my first boyfriend remained sniffy about Madonna (I think they liked a couple of “ironic” indie covers), The Immaculate Collection (1990) became the soundtrack to every girl’s pre-party dressing up session. We’d swipe random holiday-souvenir liqueurs from parents’ drinks cabinets and do each other’s eyeliner to its emboldening dance hits. We struck poses to “Vogue” and the more advanced girls rolled around on their beds in their underwear to “Justify my Love”. I got drunk on Limoncello and laughed as much as I have in my life. There was a lovely freedom and silliness in it. It took me years to realise that I always enjoyed the safe solidarity of those Immaculate Collection sessions much more than the stress of the actual parties where we were meant to be cool and not make hilarious pointy-bra gestures or leap about to “Material Girl” under showers of Monopoly money.

We struck poses to ‘Vogue’ and the more advanced girls rolled around on their beds in their underwear to ‘Justify my Love’. I got drunk on Limoncello and laughed as much as I have in my life. There was a lovely freedom and silliness in it

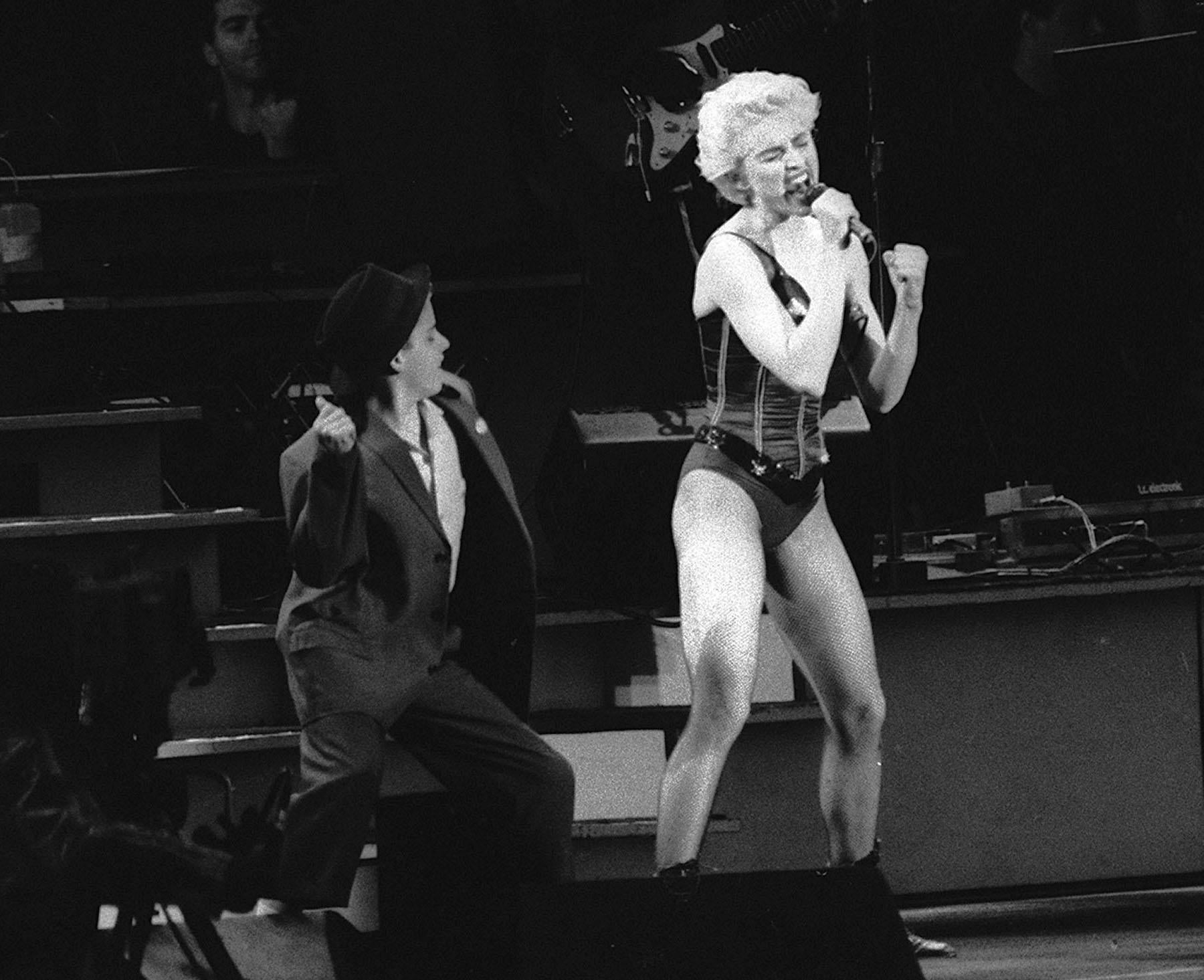

In my late teens and twenties, I’d find some of the same playful vibe at gay bars. We’d camp it up to Erotica (1992) turning her steamy lyrics into a daft ode to a bearded, bird-watching comedian: “Bill Oddie, Bill Oddie, put your hands all over my body”. There I learned the queer origins of Vogueing. In the homophobic Nineties, I came to realise that the dance floor was the only place where some of my friends really could get away with being their true selves. They were superstars under broken glitterballs down Midland side streets. Then they walked home in groups in case they were attacked. One older, very butch guy I met in a Coventry gay bar would confront bigots on the street by hiss-quoting Madonna’s whispered opening challenge from “Vogue”: “Whatchu lookin’ at?”

As my generation hit our thirties, some lost tabs on Madonna. Most of us liked the Orbit-reinvention of Ray of Light (1998) but our heroine was provoking debate again. We argued about bottles of Kabbalah water, international adoption and how much plastic surgery she was having. She was 15 years older than us, and we were trying to work out what we’d do when we hit her age. “Ageing naturally doesn’t have to mean ageing gracefully,” argued one friend. “Just look at proper feminist punks like Vivienne Westwood!” Others adopted the more modern stance that suggested good feminism meant allowing women to make their own choices about their own bodies. Madonna has always, famously, been a hard worker. If part of her work as a self-proclaimed “performance artist” meant enduring painful and expensive surgery, then that was nobody’s call but her own.

Some Gen Xers resumed their sniffiness about Madonna’s commercialism. All that money. (In 2023, Forbes named her the wealthiest female musician in history with a net worth estimated at $850m, not bad for a girl who arrived in New York with just $30 in her pocket). But it was in the early 2000s (when some of my friends believed the glass ceiling had long since been shattered) that I interviewed a CEO who told me she’d placed a job advert for her company’s Head of IT. She was startled to notice that there were no female applicants and tried an experiment. She ran the same ad – same position, hours and experience – but halved the salary offered. Women applied. How depressing. I realised that as a journalist I’d never pushed for more money than I was offered or requested fees for TV/radio appearances. It turned out my male friends did. So I began playing “Material Girl” when dealing with newspaper accounts departments to summon some of Madonna’s blunt, blonde ambition.

I dialled out – and I think Madonna did a bit – for some of the later albums including Music (2000), American Life (2003) and Hard Candy (2008). But I loved Confessions on a Dancefloor (2005). I’ve got brilliant memories of dancing around my London flat to that record’s ABBA-sampling disco pulse with fellow music critic Bernadette McNulty, who died, aged just 43, in 2018. “Dance therapy time,” she’d order, in her dry Brummie accent. “Pour yourself into some legwarmers, Helen.”

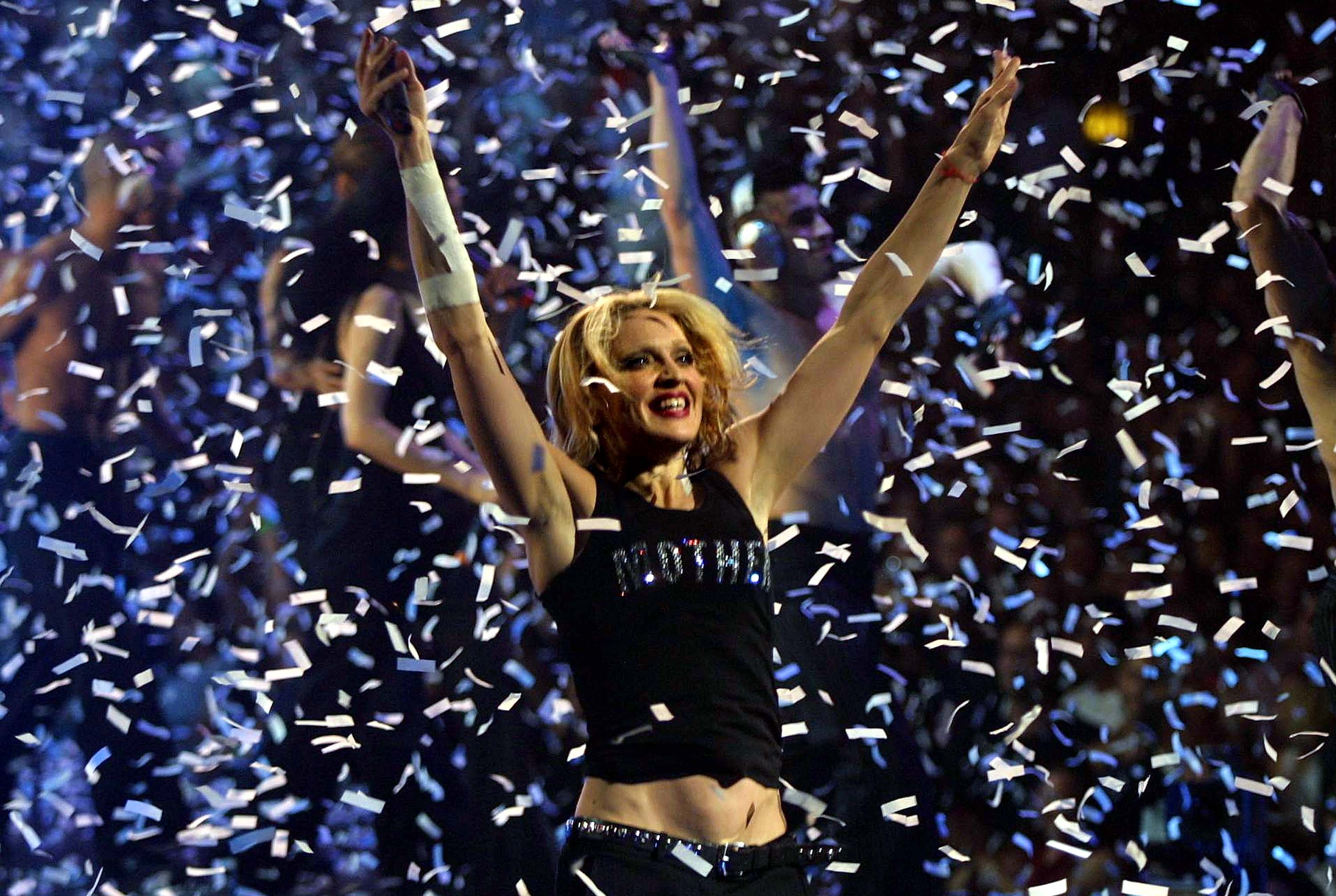

As we aged – Botox or not – Madonna refused to quit. She said the bravest and most shocking thing she’d ever done was to stick around. With depressing regularity, from 1990 onwards, commentators proclaimed her to be past her sell-by date. She fell backwards down a flight of stairs performing new song “Living for Love” at the 2015 Brit Awards, got back up and carried on singing. “You empowered me, you made me strong/ Built me up, and I can do no wrong.”

But most of us felt the same about her. Pop’s chief empowerer and provocateur; a woman who owned her contradictions in 1990 single “Rescue Me”, which is still one of my favourites. She sang of being “ferocious, weak, silly, a freak” and she embraced the parts of her that were “little girl” and “a man”. The goal of her “angry little heart” was to “conquer, and deliver and despise” the world around her.

The profound subconscious connections she made with her audience can be seen most intriguingly in Kay Turner’s 1993 book I Dream of Madonna: Women’s Dreams of the Goddess of Pop. The book celebrates the way women fantasise of a “sisterly” relationship with the star, expressing a need to protect her while basking in her reflected glory. She creeps into all kinds of odd corners of the psyche: Janet (33) apparently had a worrying dream about Madonna and Sandra Bernhard working in a frozen chicken factory, while Michelle (27) had one in which she fetches the singer a baby sheep. Monica (also 27) dreamed of offering to save Madonna from her celebrity lifestyle, while a 61-year-old grandmother dreamt of Madge snappily telling her that she looked a mess.

Into her own sixties, the self-proclaimed Madonna has continued to push the boundaries of what’s deemed acceptable, making digital art and rehearsing for a reported 12 hours per day for her Celebration tour. On 18 June, she posted on social media that she was “tired” and her final post before her hospitalisation showed her sprawled on the floor, noting that she was now experiencing “the calm before the storm”. Online, I’ve seen people confidently proclaiming that Madonna is too old for what she was attempting; that she should slow down. But that’s not their call. It’s hers. Plus, nobody’s asking them to dig out their lacey bangles and buy tickets.

One angry fan hit back at such ageist suggestions on Twitter, arguing that Madonna created the true blueprint for every pop star who came in her wake. That’s debateable. I’d suggest others – Beyonce, Billie Eilish, Amy Winehouse and Taylor Swift – have done things their own way. But Madonna cleared the way by pushing the parameters. She did more than any other to challenge the social rules for women and the LGBTQ+ community. As she sang on 2015’s “Unapologetic Bitch”: “I know you’d like it if I stayed home and cried/ But that ain’t gonna happen… Said it, did it, loved it, hated it/ I don’t care no more,” and then with a wink, “Tell me how it feels to be ignored?” Good luck to the medical staff trying to tell Madonna to take it easy. I hope she listens to them, gets well soon and gives us all that “big Madge boogie” when she’s good and ready.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments