Lou Reed: The truth about the singer's upbringing beyond the biographers' and memoirists' myths

Lou Reed distorted the truth about his upbringing and, since his death in 2013, people have only added to the myths. Merrill Reed Weiner, a family therapist and sister of the musician, aims to set the medical record straight

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

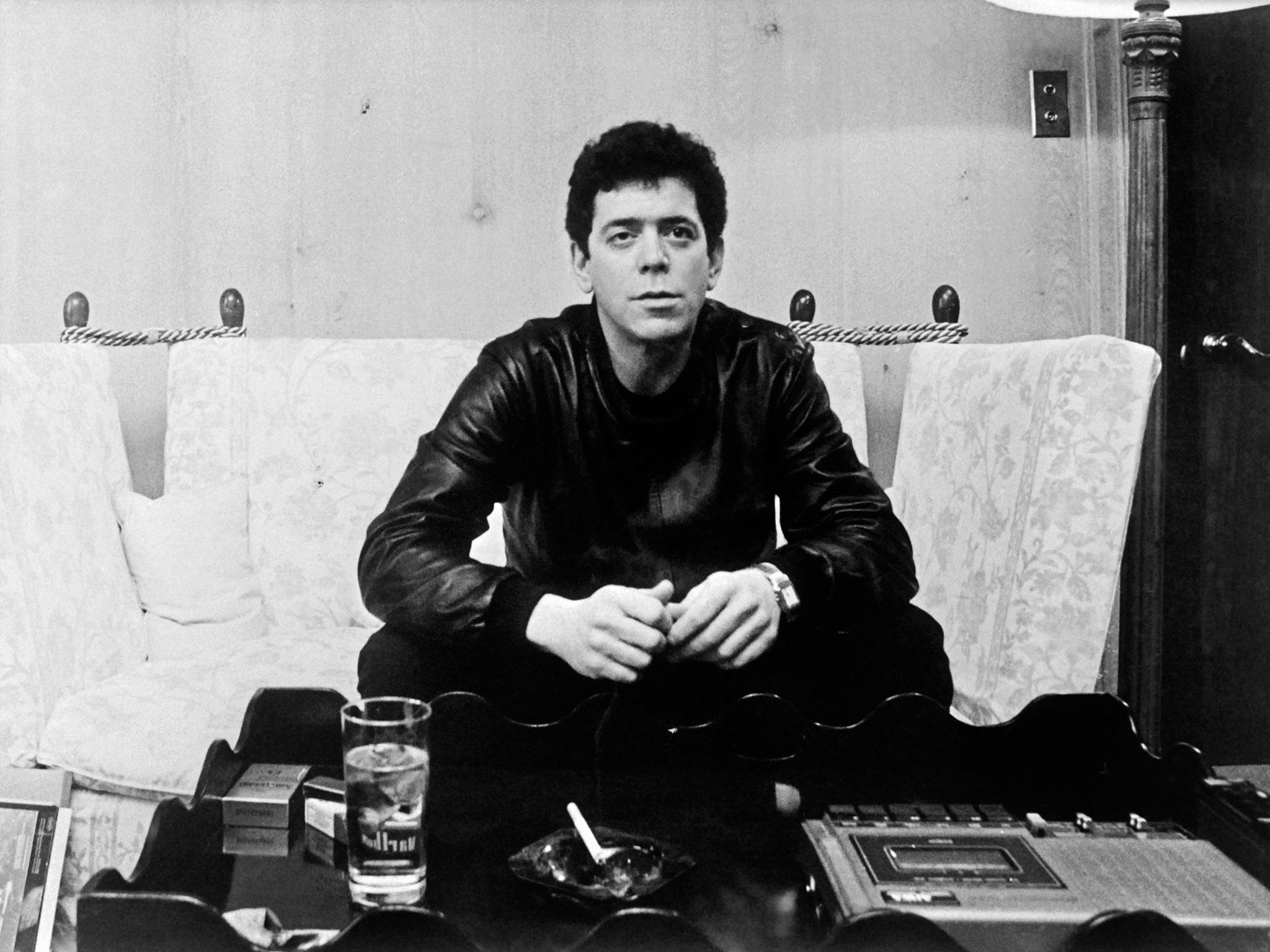

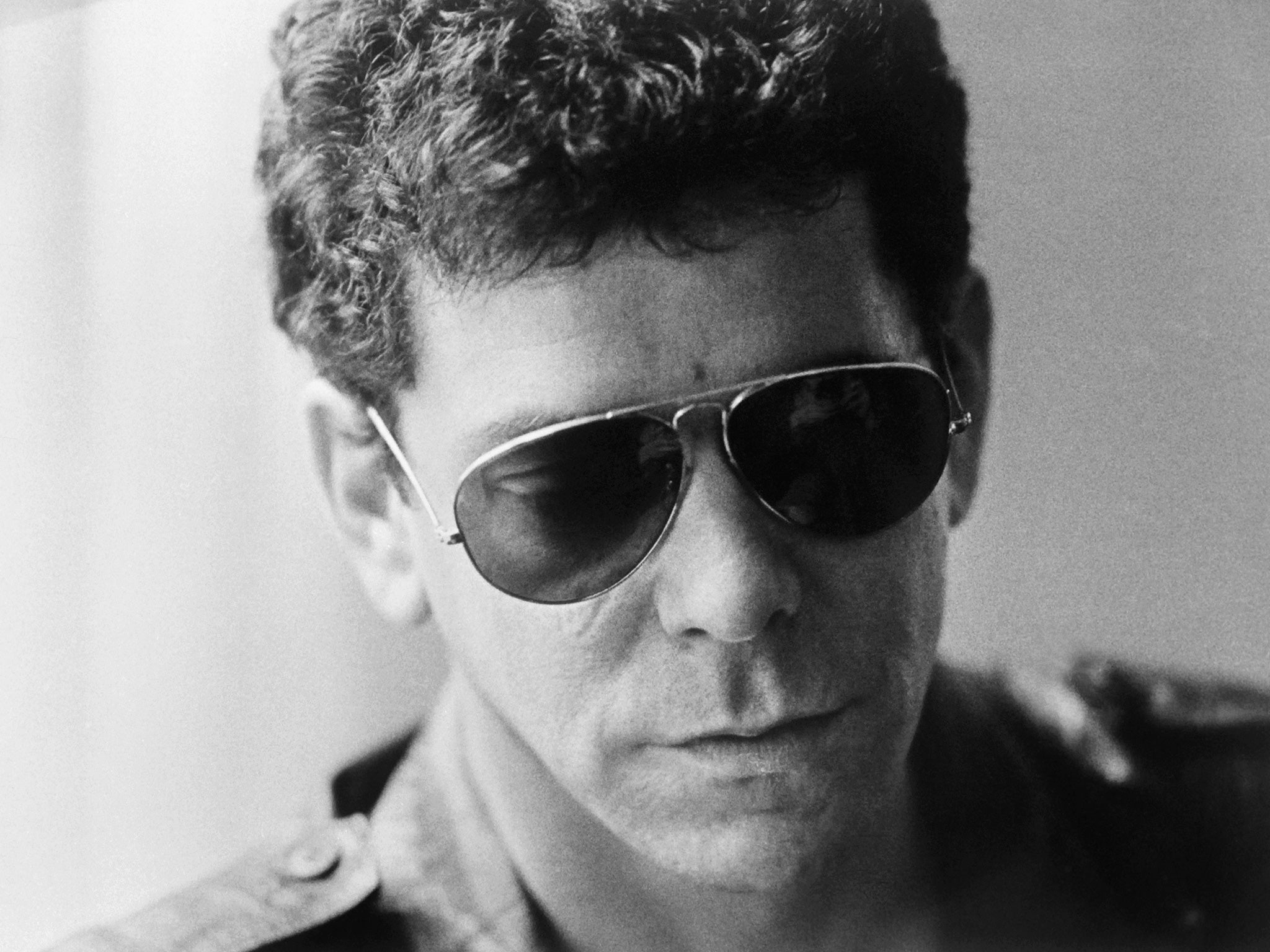

Your support makes all the difference.Today, my brother, Lou Reed, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a solo performer, an honour celebrating his incredible impact upon the world of music. Since his passing from liver disease in 2013, there have been many accolades, articles, and ruminations on his life. As biographers have begun in earnest to explore every aspect of that life, there has been speculation about the childhood issues that contributed to his artistic genius.

With this piece I hope to shed light on this part of his life, as it has been inaccurately portrayed by other authors, to the detriment of my family. For all those whose families’ lives were damaged by the pervasive medical thinking of the time, I hope to offer solace and comfort.

We were an average middle-class Jewish family. My mother, Toby, was a housewife and doting mother. Her claim to fame had been her selection as “Queen of the Stenographers of NYC”, a beauty pageant that came to her firm in 1939 and picked her as their winner. My mother says she only won because “the really pretty stenographer was out sick that day”. She was just 19. Her father had passed away when she was a teenager and she had left school to contribute financially to her family. A product of her times, she married young and took on a traditional role as a homemaker, wife and mother.

My father, Sidney, had dreamed of becoming an author or lawyer but instead became a certified public accountant as his mother wished. After struggling to find work during the Depression, he began to achieve a modest measure of success with a new job as the treasurer for Cellu-Craft, a small manufacturing company located on Long Island.

The new job meant my parents could move out of Brooklyn, where Lou and I were born, and achieve everyone’s dream at that time, owning their own home. For $10,000, my parents bought a small three-bedroom ranch house in the blue-collar community of Freeport, on the south shore of Long Island. They settled there in 1952 to raise Lou and myself.

For nine-year-old Lou, the move from Brooklyn to Freeport was a difficult transition. Brooklyn was an environment where kids just walked outside to play – a diverse and energetic city with a heterogeneous population. Long Island at that time was in its early stages of development, with tracts of new homes and lots of empty space, a far cry from the more sophisticated and diverse environment it is now.

During those first years in our Freeport home, we were quite isolated. The only car my family owned was needed by my father to travel to work. Even buying groceries meant walking to the market. We knew no one and my mother didn’t work. The social setting my parents had known was suddenly removed from them. Lou began Atkinson Elementary School while I, only four at the time, stayed home with my mom. I would wait patiently by the window to see him walk home from school each afternoon, always alone.

Junior high was another matter. In later years, Lou spoke of being beaten up routinely after school at Freeport Junior High School, which boasted a number of gangs at the time. However, our next-door neighbour told me, years later, that Lou was challenging, unfriendly, provocative even, daring him to “cross that line on to my property and you’ll see what happens”.

During Lou’s teenage years, it became obvious that he was becoming increasingly anxious, psychologically “avoidant” and resistant to most socialising, unless it was on his terms. In social situations he withdrew, locking himself in his room, refusing to meet people. At times, he would hide under his desk. Panic attacks and social phobias beset him. He possessed a fragile temperament. His hyper-focus on the things he liked led him to music and it was there that he found himself.

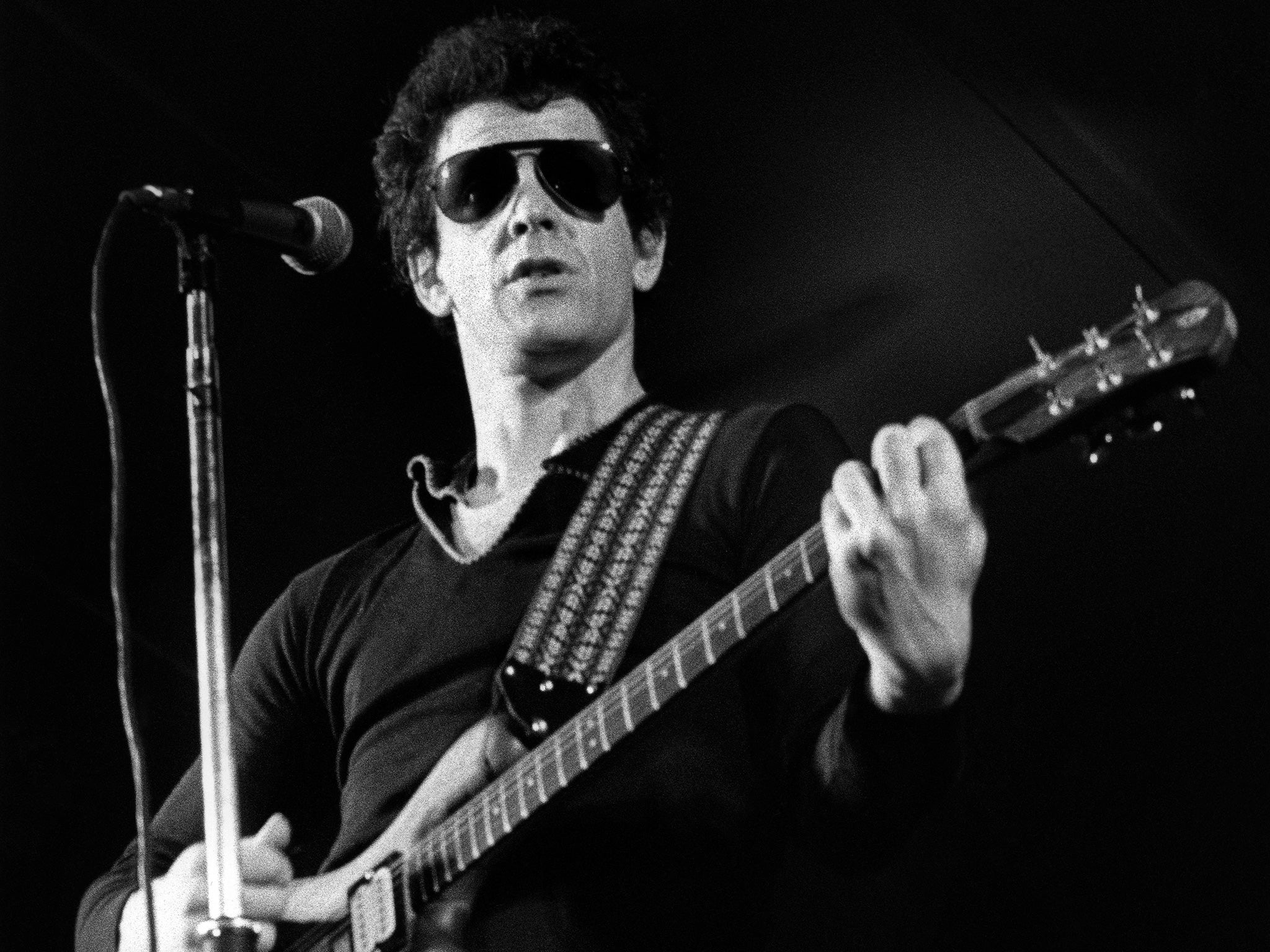

Self-taught, he began playing the guitar, absorbing every musical influence he could. In high school he formed bands and played in the school variety shows. His band began to get dates at small local clubs, which then expanded to playing gigs in New York City. By the age of 16 he was experimenting with drugs and closing the door on any communication with our parents. Verbal fights between Lou and my parents erupted – about going into the city to play band dates, about the dangers he might confront. My parents were frightened, upset and bewildered. This was uncharted territory for Toby and Sid, children of the Depression era who had never disobeyed their own parents. Lou’s behaviour terrified them and they were ill-equipped to know how to respond.

Anxious and dependent by nature, my mother appeared helpless, leaning on my father to make things better. My father, a controlling man who never mastered flexibility – not unusual in those days – was used to getting his own way. He resorted to old techniques, setting rules and yelling. Nothing worked. He was overwhelmed by Lou’s disregard. As much as he probably thought he was trying to protect Lou, he only made things worse.

The stage was set. Anxious, controlling parents, a child whose issues exceeded their understanding, a society that valued secrecy, underlying mental health issues ; add in rock’n’roll and drugs and the drama began. I don’t know how aware my parents were of Lou’s drug use. Certainly there were times when he seemed drugged, as I look back on it. Once, he crashed the family car into a toll booth. Yet my parents did not seek help at that point. Perhaps because that wasn’t what you did at the time, or because they just didn’t understand what was happening. They were embroiled in a battle that overwhelmed their resources.

Family secrecy still ruled the day. This was before Oprah and the willingness of individuals to confess to substance abuse or mental illness. Rehabilitation facilities were essentially non-existent. Fright paralysed my parents, and as a result they did nothing. They pretended that the problem did not exist. Meanwhile, Lou continued to self-medicate with drugs and alcohol.

Remarkably, during Lou’s senior year in high school, there were moments of normality at home. Family dinners could be enjoyable. Lou and my father were both extremely witty, with erudite, dry senses of humour and remarkable literary sensibilities. I enjoyed their verbal jousting, as did they. Just a child at the time, perhaps 11 years old, I was dazzled by it. Their cleverness was something we all enjoyed together. At 17, the decision was made that Lou would attend New York University. My parents sent him off with pride and possible trepidation. They were about to encounter some very difficult issues with their son and the “help” they received from the medical community set in motion the dissolution of my family.

Within the Hippocratic oath lies the promise that doctors will “do no harm and avoid injustice” to patients. We trust and hope that those in the medical profession will use their knowledge and skill to save our loved ones. Yet the 1960s were marked with psychiatric theories that would ultimately harm families and do irreparable damage – for example, by blaming mothers for being “refrigerator mothers” who “caused” autism or schizophrenia. Families at a loss how to deal with their loved ones’ genetically based mental illness were treated as perpetrators by the psychiatric establishment. They were blamed for poor parenting, left feeling hopeless and guilty.

Some time during his freshman year at NYU, when I was 12, my parents went to the city and returned with Lou, limp and unresponsive. I was terrified and uncomprehending. They said he had had a “nervous breakdown”. The family secret was tightly kept and the entire matter was concealed from relatives and from friends. It was our private and unspoken burden. Even at 12, I knew to keep silent, and I did.

My parents finally sought professional help for Lou. I heard only the superficial pieces of what was going on. My mother came into my room and told me that they thought he might have schizophrenia. She said that the doctors told her it was because she had not picked him up enough as an infant, but had let him cry in his room. She sobbed. “The paediatrician told me to do that! He said that’s how you teach a baby to go to sleep.” It was a belief and a burden she took to her grave.

Lou was not able to function at that time. He was depressed, anxious and unresponsive. If people came into our home, he hid in his room. He might sit with us, but he looked dead-eyed, non-communicative. I remember one evening when all of us were sitting in our den, watching television together. Out of nowhere Lou began laughing maniacally. We all sat frozen in place. My parents did nothing, said nothing, and ignored it as if it was not taking place.

He did not improve. Despite their misgivings, my parents took a deep breath and brought Lou to a psychiatrist. Who knows what happened in the therapy setting? I only know that the treating psychiatrist recommended electroshock therapy. Did that doctor take into account the possibility of the impact of Lou’s substance abuse or any familial context? Did any sort of family therapy get offered to help us process what was happening?

My parents were like lambs being led to the slaughter – confused, terrified, and conditioned to follow the advice of doctors. They never even got a second opinion. Told by doctors that they were to blame and that their son suffered from severe mental illness, they thought they had no choice. I assume that Lou could not have been in any shape to really understand the treatment or the side-effects. It may well be that he was fearful he would be committed to a psychiatric hospital and not allowed to return home if he did not agree to the treatment. Thus, informed consent from him would have been obtained in a rather questionable fashion.

Was he suicidal? Impaired by drugs? Schizophrenic? Or a victim of psychiatric incompetence and misdiagnosis? Certainly no one was talking about the impact of depression, anxiety, self-medication with illegal drugs, and what all that could do to a developing teenage brain. Nor was there any family therapy, involving us in understanding him and his needs.

My father was attempting to solve a situation that was beyond him, but it came from a deep love for Lou. My mother was terrified and certain of her own implicit guilt from what she had been told was her poor mothering. Each of us suffered the loss of our dear, sweet Lou in our own private hell, unhelped and undercut by the medical profession. Family therapy, unfortunately, was not yet available. We were captured in a moment in time.

It has been suggested by some authors that ECT was approved by my parents because Lou had confessed to homosexual urges. How simplistic. He was depressed, weird, anxious, and avoidant. My parents were many things, but homophobic they were not. In fact, they were blazing liberals. They were caught in a bewildering web of guilt, fear and poor psychiatric care. Did they make a mistake in not challenging the doctor’s recommendation for ECT? Absolutely. I have no doubt they regretted it until the day they died. But the family secret continued. We absolutely never spoke about the treatments, then or ever.

Our family was torn apart the day they began those wretched treatments. I watched my brother as my parents assisted him coming back into our home afterwards, unable to walk, stupor-like. It damaged his short-term memory horribly and throughout his life he struggled with memory retention, probably directly as a result of those treatments.

But Lou did get better. After he recovered, he and my parents decided he should go off to Syracuse University and begin again. And he did. The rest, as they say, is history. His musical genius, his poetry, and his legacy have had an impact on many people and will continue to do so for generations to come.

Would it have happened if he had received better psychiatric care, if my family had received better support? Could my parents have been spared their guilt, encouraged to do better than they did? Would Lou have become the artist he became without the furious anger that the treatments engendered? Did Lou use the treatments as artistic fuel to create an illusion of an abused individual? Who knows?

Even though Lou returned home sometimes seeking nurture and support, through other breakdowns, he harboured incredible rage, particularly towards our father. Lou’s accusations towards our father, of violence and a lack of love, seemed rooted in that time. The stories he related – of being hit, of being treated like an inanimate object – seemed total fantasy to me. I must say that I never saw my father raise a hand to anyone, certainly not to us and never to my mother. Nor did I see a lack of love for his son during our childhood. Like his son, my father could be a verbal bully but he was loving and inordinately proud of Lou and bragged about him in later life to anyone who would listen.

Remarkably, Lou managed to live a full and vibrant 71 years, despite the many emotional issues that pursued him thoughout his life. His charisma, his charm, his wit, his intellect were undeniable and seductive to everyone who knew him well. And, yes, his rage was lethal and unforgiving. But through it all I loved him, tenderly and without reservation. He and I remained brother and sister right to the end.

The lessons of that time helped me to create my own family, with a loving husband of 43 years and three wonderful children. It made me a more compassionate family therapist. And it made me sensitive to the plight of so many families, criticised and left without support through such difficult times. Do no harm indeed.

This article was first published on medium.com under the headline ‘A Family in Peril: Lou Reed’s Sister Sets the Record Straight About His Childhood’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments