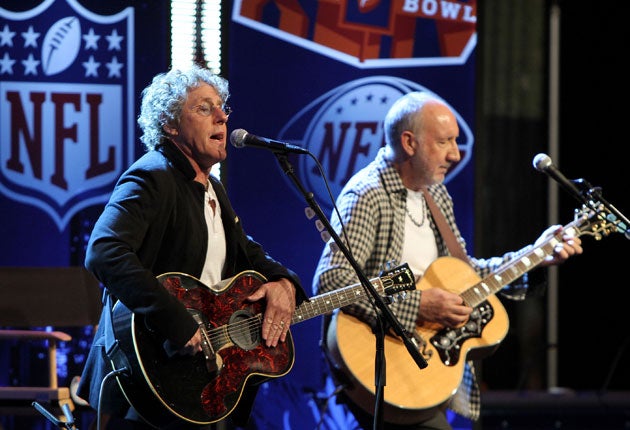

Long live rock! The Who at the Super Bowl

Their generation? Bus-pass holders heading for the Zimmer. Yet tonight, resurgent in the US after five decades in the business, they play the Super Bowl. Barney Hoskyns salutes The Who

Arguably the most famous line The Who's Pete Townshend ever wrote was "Hope I die before I get old" on the angry young anthem of 1965, "My Generation". Tonight, at the Beatle-esque age of 64, Townshend will – in his own words – "carry the flag for the boomer generation" during the half-time show at Super Bowl XLIV in Miami. The entertainment spotlight doesn't burn much brighter. It may even remind the world just how great The Who once were.

The group have long had to settle for third place in the pantheon of Sixties rock giants behind The Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Many, though, would argue that they were the greatest live band of all time, ahead not only of The Beatles and the Stones, but also of Led Zeppelin, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Nirvana and pretty much anyone else you'd care to mention.

Nor is that reputation a case of The Who resting on their Sixties and Seventies laurels. When Townshend and singer Roger Daltrey – the other surviving original member of the group after the deaths of drummer Keith Moon and bass guitarist John Entwistle – played the post-9/11 Concert for New York City, their passionate performance had traumatised firemen on their feet with tears of rage in their eyes. Tonight's Super Bowl set – apparently a "mashup" of "Pinball Wizard", "Who Are You", "Baba O'Riley", "Won't Get Fooled Again" and the finale to Tommy – gives the duo an opportunity to remind the world that the Stones' Greatest Rock'n'Roll Band in the World crown was merely one Mick Jagger and Keith Richards bestowed on themselves.

And if that multimillion-dollar showcase isn't enough for you, 2010 will see new performances of The Who's 1973 "mod opera" Quadrophenia and possibly the recording of a new Who album based on Townshend's current work-in-progress Floss.

It was live performance that set The Who apart from rivals at the dawn of their career as the west London mod combo The Detours. Their explosive shows were built on the kinetic interplay between Entwistle's growling bass lines and the crashing, trebly violence of Townshend's guitar and Moon's manic drumming.

Quickly outgrowing their role as the de facto house band for London's mod scene, The Who established themselves as poster boys for intelligent delinquency, their songs declarations of war on the middle aged and middle class. "Ours is a group with built-in hate," Townshend announced from the stage when The Who played a Tuesday night residency at London's Marquee club. On "Substitute", Daltrey famously snarled that he was "born with a plastic spoon in my mouth".

Townshend was Will Self with a Rickenbacker guitar, a misfit icon of choice for every bedroom pop star who didn't look like Roger Daltrey. His rage and self-loathing spewed out on stage in wheeling arm slashes and what he termed the "auto-destruction" of his guitars, beginning one night in September 1964 at the Railway Tavern in Harrow and Wealdstone. "They're a new form of crime," their gay upper-class manager Kit Lambert purred approvingly in March 1966, "armed against the bourgeoisie". In all but name, it was punk rock a decade ahead of its time: no wonder the Sex Pistols would cover "Substitute".

Not surprisingly, The Who were wholly at odds with late Sixties American vibes of peace and love. At the world-changing Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967, they offered a pointed British contrast to the California bands Buffalo Springfield (who preceded them) and the Grateful Dead, who followed. Although Daltrey had transformed himself from a Carnaby Street mod "face" into the tousle-headed rock god of the band's performance at Woodstock, Townshend was so incensed when stoned activist Abbie Hoffman interrupted their set at that festival that he clouted him over the head with his guitar, yelling, "Fuck off my fucking stage!"

Too smart and too cynical to trot out the flower-power rhetoric of his peers, Townshend at heart remained a bolshy punk rocker. In the early Seventies, he eschewed the threads of stadium superstardom by sporting white boiler suits and Doc Martens. "I thought: 'Fuck it,'" he later reminisced, "'I'll just wear work clothes.'" Or perhaps he simply wanted to look as unlike Roger Daltrey – with his perfect torso and fringed Comanche waistcoat – as possible. Years later, he claimed that every Who concert was a competition for attention between him, Moon and Daltrey – "and Daltrey always lost".

Townshend's restless intelligence pushed him to conceive ambitious art-rock projects far beyond the scope of conventional rock releases. A Quick One (1966) and The Who Sell Out (1967) were early examples of "concept albums". With Tommy (1969), about a deaf, dumb and blind pinball wizard, he single-handedly gave birth to the rock opera as we came to know (and dread) it. That was followed in turn by the mod magnum opus Quadrophenia (1973), a double album dedicated to "the kids of Goldhawk Road, Carpenters Park, Stevenage New Town and to all the people we played to at the Marquee and Brighton Aquarium in the summer of 1965". Due to be performed next month at London's Albert Hall in aid of the Teenage Cancer Trust, the revisited Quadrophenia capitalises not simply on the much-loved 1979 film with Phil Daniels and Sting, but on acclaimed shows staged in 1996 in London and New York.

Townshend had cemented his intellectual credentials with a collection of verse, Horse's Neck (1984), and a stint as an editor at Faber & Faber, commissioning among other titles Charles Shaar Murray's Jimi Hendrix biography Crosstown Traffic. A side effect of his need to challenge himself – sometime verging on the pretentious – has been a dearth of "classic albums of the kind routinely produced by The Beatles, the Stones and Led Zeppelin, and this, in turn, has dented The Who's long-term reputation. Only Who's Next in 1971 – featuring the angst-ridden "Behind Blue Eyes", "Baba O'Riley" and the mighty "Won't Get Fooled Again" (both the latter tracks used as theme songs in the forensic TV franchise CSI) – stands as an unequivocally great studio album.

Arguably The Who's standing also suffers somewhat from Townshend's overshadowing of Daltrey, who tends to be associated with such uncool pastimes as trout farms and the Countryside Alliance.

Live – as this writer can attest from seeing them as a teenager at Charlton in 1974 and Wembley in 1975 – the Moon-fuelled Who were astonishingly exciting. Live at Leeds, released in 1970 and recorded on the Tommy tour at the city's university, is regularly and rightly hailed as the greatest live album of all time.

The Who were never really the same after deranged Keith Moon – a drunken cross between Ian Dury and the Dudley Moore of Derek & Clive – died in 1978. But unlike Led Zeppelin, who called it a day after the death of their drummer John Bonham, The Who soldiered on into the early Eighties with the more cautious Kenney Jones in the drum seat. Little that the band has done since then – from Face Dances in 1981 to Endless Wire in 2006 – touches their former glories. But Townshend has recovered from drug addiction to mature into one of rock's more revered elder statesmen. Moreover, he and Daltrey have not only survived John Entwistle's death but overcome their long mutual antipathy and learned to love each other. It's all rather touching and even a little heroic.

The taint of the child-pornography charges brought against Townshend in 2003 – he claimed he was merely researching for his work, and the charges were dropped – will unfortunately always stick to The Who guitarist. It is to the credit of the Super Bowl organisers that they have ignored hysterical protests against The Who's half-time show appearance by American groups such as Protect Our Children.

Pete Townshend is as busy as ever, if a little less restless and self-loathing. He is currently finishing Floss, a "musical play" – pipe down whoever said "rock opera" – about an ageing musician and his horse-obsessed daughter (who, as it happens, writes a gardening column in the magazine of this newspaper). Maybe he even hopes he'll get old before he dies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks