Giddy stratospheres: How The Long Blondes saved landfill indie

The Sheffield band were a breath of fresh air on the mid-2000s guitar scene and for a time, everyone wanted to wear a neckerchief like singer Kate Jackson. As their seminal debut turns 15, they talk to Ed Power about misogyny, reunions and why Razorlight were not really friends

In March 2007, under the spotlight in a heaving arena, Kate Jackson of Sheffield five-piece The Long Blondes stamped on a man’s hand until she drew blood. “I remember playing gigs when we were supporting Kaiser Chiefs,” she says of their Leeds peers. “This is not Kaiser Chiefs’ fault at all but their audience, in particular, was not willing to appreciate a band with women in it. A guy tried to get on stage and dry hump me, which was horrible.”

Fourteen years on some of the details are blur – such as the venue where the incident occurred. Nevertheless, she winces at the memory. “I pushed him off the stage. And then he put his hand on the stage, to try and get back up again. And I was wearing fierce stiletto heels. I just trod on him. I trod on him as hard as I could. And sang the rest of the song in his face, until he was bleeding. I felt pretty good about it.”

Jackson is speaking over Zoom as The Long Blondes, among the brightest stars of the UK’s mid-2000s indie scene, mark the 15th anniversary of their debut album with a deluxe re-release. She remembers the good times: three top 40 singles, sell-out gigs in America, a main stage appearance at Reading Festival. But she also remembers the bad ones – in particular the group’s premature disintegration in October 2008 after songwriter and guitarist Dorian Cox suffered a near-fatal stroke.

A recurring theme of our conversation, however, is the contempt with which alternative music often held women back then, in the era of gossip rag nastiness and pre-#MeToo unaccountability. “As you can imagine, it was totally horrendous,” says Jackson. “We got booed every night [supporting Kaiser Chiefs]. I had ‘get your t**s out’ [shouted at me] all the time. And I had no patience with it whatsoever. We faced a hell of a lot of misogyny – abuse really – from inside and outside the industry. You’d get sound engineers who’d always be like, ‘No girlfriends in the dressing room’. And we’d be like, ‘Yeah… we’re in the band.’”

British rock at the time was dominated by identikit lads who took their image from The Strokes and their musical inspirations from the lairy fringes of Britpop. This was the era of Arctic Monkeys, The Libertines and The Fratellis – brash upstarts who sounded like the musical equivalent of a bloke’s night down the pub, their music a boozy mix of raucous guitars and terrace chant choruses. Amid the leather jackets and lank hair – key ingredients of what would come to be known as “landfill indie” – The Long Blondes cut a fantastical dash.

That was partly down to their music, which welded buzzing guitars to kitchen sink explorations of social class and Belle and Sebastian-styled tales of underdog love and loss. They took lyrical inspiration from Warhol muse Edie Sedgwick and the cinema of Lindsay Anderson. Jackson’s cover art for 2006’s Someone to Drive You Home captured their high-art/low art philosophy with its image of a Bonnie and Clyde-era Faye Dunaway leaning on a Mark 3 Ford Cortina.

Yet much of the allure flowed from Jackson herself, who radiated gale-force charisma. And who, in signature beret and neck scarf, blazed a trail with her preppy fashion sense (this afternoon her beret is present and correct as she beams in from the site of an art installation she is working on in Leicester, where she has lived for several years).

Cox, joining by Zoom from his home in Manchester, says that Jackson’s stage presence was key. “I just looked at you and I was like, ‘You’re a frontwoman’ straight away,” he says, recalling the moment he walked up to Jackson and told her he wanted her to be the singer in his project. “People think that’s a lie but it’s 100 per cent true. It was like, ‘I don’t know if you can sing. I’m starting a band. I need you to be the front person.’”

The Long Blondes were formed in 2003 in Sheffield, where Jackson (from Bury St Edmunds) and Cox (from York) were studying. With Kathryn “Reenie” Hollis playing bass, Emma Chaplin on rhythm guitar and Mark Turvey drumming, the band was unusual in that they were a majority-female group. Coming from Sheffield, they also felt like natural-born outsiders. Although it had given the world Arctic Monkeys, the city at that time had a far more fragmented music scene than was the case with other big urban centres in the north.

Despite their sense of existing apart, the music press tried to lump them in with other bands from Sheffield and Leeds, “We were kind of [pigeonholed] with ‘New Yorkshire’,” says Jackson, referring to a made-up scene touted by the NME and which supposedly included the Arctic Monkeys, Little Man Tate and Reverend and the Makers from Sheffield, and Leeds groups such as Pigeon Detectives and Dead Disco. “That was something of a construct.”

And yet, despite materialising in an age in which Pete Doherty was legitimately regarded as a national poet in a porkpie hat, The Long Blondes stood apart. They were a genuine sensation. Their 2004 debut single “New Idols” was released on indie label Thee Sheffield Phonographic Corporation, who signed The Long Blondes after just their third gig, and they soon pricked the ears of Rough Trade, who signed them off the back of an NME New Music Tour in 2006.

On 6 November that year they released Someone to Drive You Home. Fuelled by Jackson’s emphatic vocals – she sounds like Kate Bush if Kate Bush was really into Pixies and The Strokes – and by Cox’s whip-smart guitars, the album was arch and catchy. It reached a place of pure exhilaration with the single “Giddy Stratospheres”. With a teasing call-and-response chorus between Jackson and Hollis and Chaplin, the song marked The Long Blondes out as very different to the huffing, puffing indie boys of the era and was a definitive alternative anthem of that period.

Yet alongside these sprinklings of joy, Someone to Drive You Home was layered with darkness. “Separated by Motorways” is Thelma and Louise in the rain, with two female protagonists escaping small-town misogyny by driving off into a drizzle-flecked sunset. And on “Once and Never Again” – a shiny banger full of shadows – the narrator urges a younger woman to get out of a coercive relationship. “Look what he’s made you do to your arm again/ He said he’d come round but he’s gone out with his friends,” sings Jackson.

“We’re in a different world now,” says Cox, who wrote the bulk of The Long Blonde’s music and lyrics. “The idea of gaslighting and even to some extent the leaps and bounds that feminism and trans rights and things like that have made in the last 15 years weren’t around that that point, when those songs were written.”

It was an exciting time to be in a band – or be a fan of one. Walking down Camden High Street in London on any given day, there was a decent chance you might bump into Pete Doherty or Amy Winehouse. As Cox actually did one afternoon.

We’re in a different world now

“You always crossed paths with those kind of people. More particularly if you went to Trash, which was Erol Alkan’s night and which was the best club around at the time. Every Monday, you went there and it was a bit of a Who’s Who of bands around at the time. I used to know Amy very, very vaguely from going to Trash, just because she’d always be there. One day, I was walking through Camden and she shouted me out on the other side of the road. She was like, did I want to go for a drink? It was just one of the funniest afternoons in my life, drinking with Amy. I’d been to Camden to buy some records. I got so drunk that I forgot to take them back with me.”

But, like Winehouse’s, The Long Blondes’ career was cut short. In June 2008 Cox suffered a stroke. He was lucky to survive and says recovery remains an ongoing process. “It really was completely out of the blue,” he says. “There’s no history of it in my family. I guess I was one of the unfortunate ones. All credit to the NHS because I wouldn’t be here now if it wasn’t for them. I was technically dead and they sorted me out.”

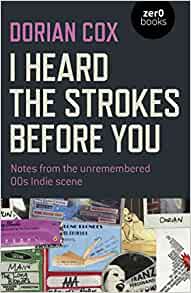

Cox has written a book about his adventures on the fringes of landfill indie. I Heard The Strokes Before You is due to be published in October 2022 by Zer0 Books and will, he promises, be gossipy and full of jaw-dropping anecdotes. “Part of it is quite salacious,” he confides. “I may have to hire a lawyer.”

“Landfill indie” was the pejorative term that came to be applied to the dregs of the British guitar scene in the mid-2000s, when the “movement” defined by angular guitars, tight jeans, flailing hair and jangling choruses was reaching its event horizon and identikit bands like The Pigeon Detectives, The View and The Enemy blew up. Fairly or unfairly, it has come to be seen as a low-point for British music – and indeed culture more generally. It undoubtedly lacked the wit and self-parodying aspects of the best Britpop. And it was largely white and overwhelmingly blokey – as The Long Blondes discovered when they were mistaken for girlfriends sneaking into the headliners’s dressing room.

“It’s like any other scene. Yes, there were a lot of terrible, terrible bands around,” says Cox. “Then again, there were a lot of terrible, terrible bands around during Britpop.”

Landfill indie was also, he alleges, packed to the brim with manufactured groups. “Bands like The Kooks or Razorlight – you could tell they weren’t friends who’d formed a band. It was the industry who had put those people together.”

Cox was unable to play guitar for years following his stroke. It prematurely brought down the curtains on The Long Blondes in 2008, after their Erol Alkan-produced second record Couples (“one of the albums of the year from one of the bands of the decade,” raved The Independent). While of course relieved her friend was still alive, Jackson found the band’s demise difficult to deal with and didn’t know what to do with herself.

“After Dorian’s stroke I couldn’t listen to the band,” she says. “I knew I had to try to find out who I was without it. That’s a difficult thing. To make that transition from doing something you love, which is a career trajectory you thought you were going to be doing for a long time, to suddenly not doing that… This was the problem I had to solve in my thirties: ‘What the hell am I going to do with my life now?’”

Since The Long Blondes, Jackson’s greatest success has been as a visual artist. She specialises in paintings that cast urban vistas often regarded as grim in a romantic light. “Musically and aesthetically it’s about opening people’s eyes to beauty that they wouldn’t necessarily notice,” she says. “Things you might walk past like, say, a shopping centre, brutalist architecture, flyovers.” Cox has for his part continued with his recovery. The rest of The Long Blondes have moved on, too. Hollis works in digital recruitment for the education sector in Sheffield; Turvey is head of school at University Academy Keighley in West Yorkshire.

The Long Blondes are now 13 years defunct. But Jackson and Cox recently worked together on a sound loop for the art installation that Jackson will unveil in Leicester on 17 December, titled Built for Sound. They were astonished to discover how much of the old chemistry endured. And while they won’t go so far as to confirm a potential Long Blondes reunion, they’re not ruling one out either.

“We’re open to discussing it,” says Jackson.

“What’s the politician’s answer to that?” adds Cox. “Reading between the lines, well we are not saying we aren’t.”

‘Someone to Drive You Home: 15th Anniversary Edition’ is on Rough Trade

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks