Liam Gallagher and John Squire on their two-man supergroup: ‘At the end of the day we’re here to sell records’

Rock’s lairiest lead singer and The Stone Roses’ guitar maestro talk to Laura Barton about their new album, singing drunk and the power of the earthing mat

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For the past few weeks, Liam Gallagher and John Squire have been busy familiarising themselves with material for their upcoming tour. Squire driving around near his home close to Macclesfield listening obsessively to the record they made together, admiring the drums and the production. Meanwhile, Gallagher has taken a different tack. “I’ve been singing them round the house drunk,” he says, listing the tracks that sound particularly fine when inebriated: “‘Rainbow’. ‘Mars to Liverpool’. ‘Raise your Hands’. ‘Mother Nature’s Song’. They’re all vibing man, I’m buzzing.”

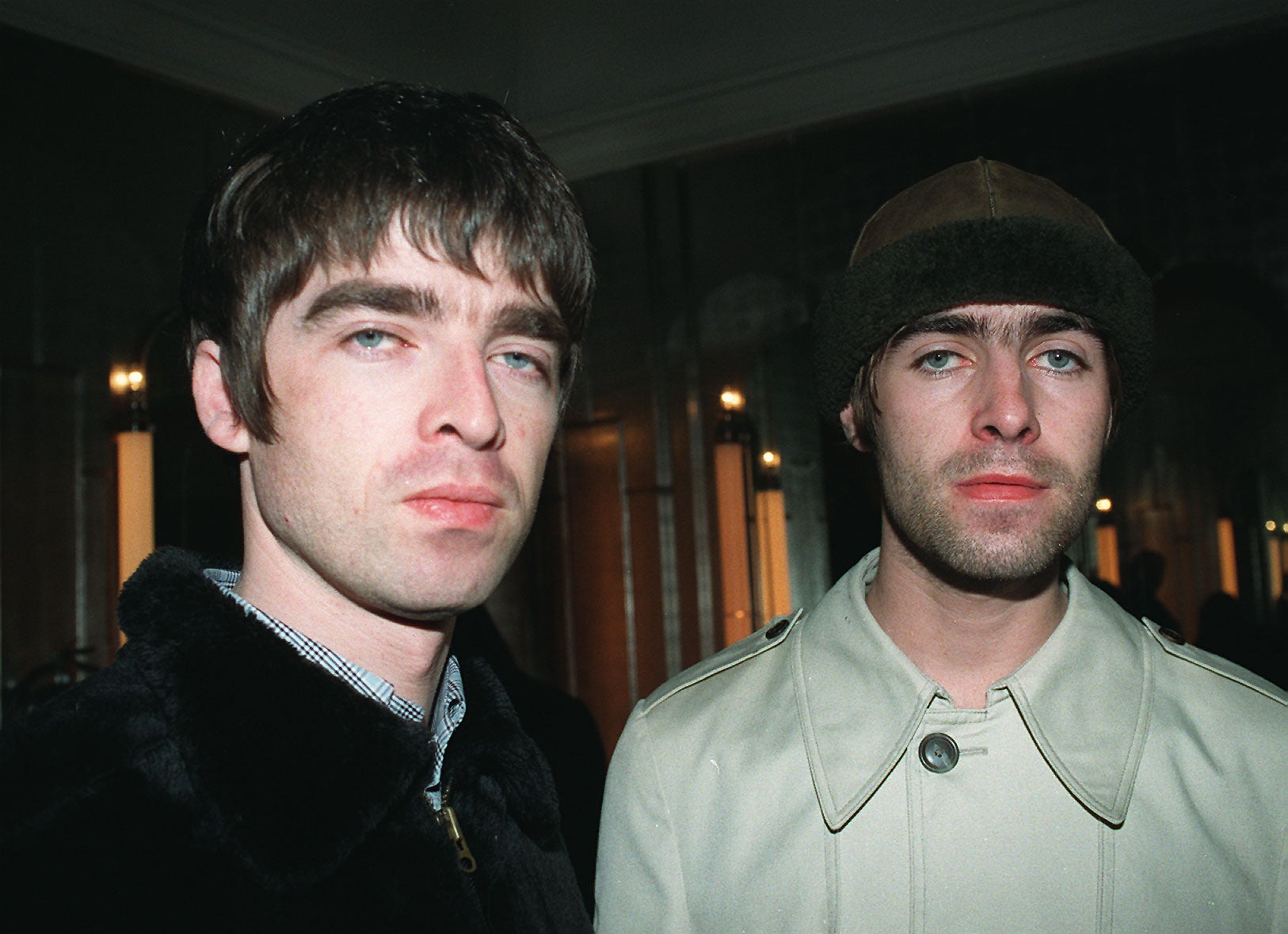

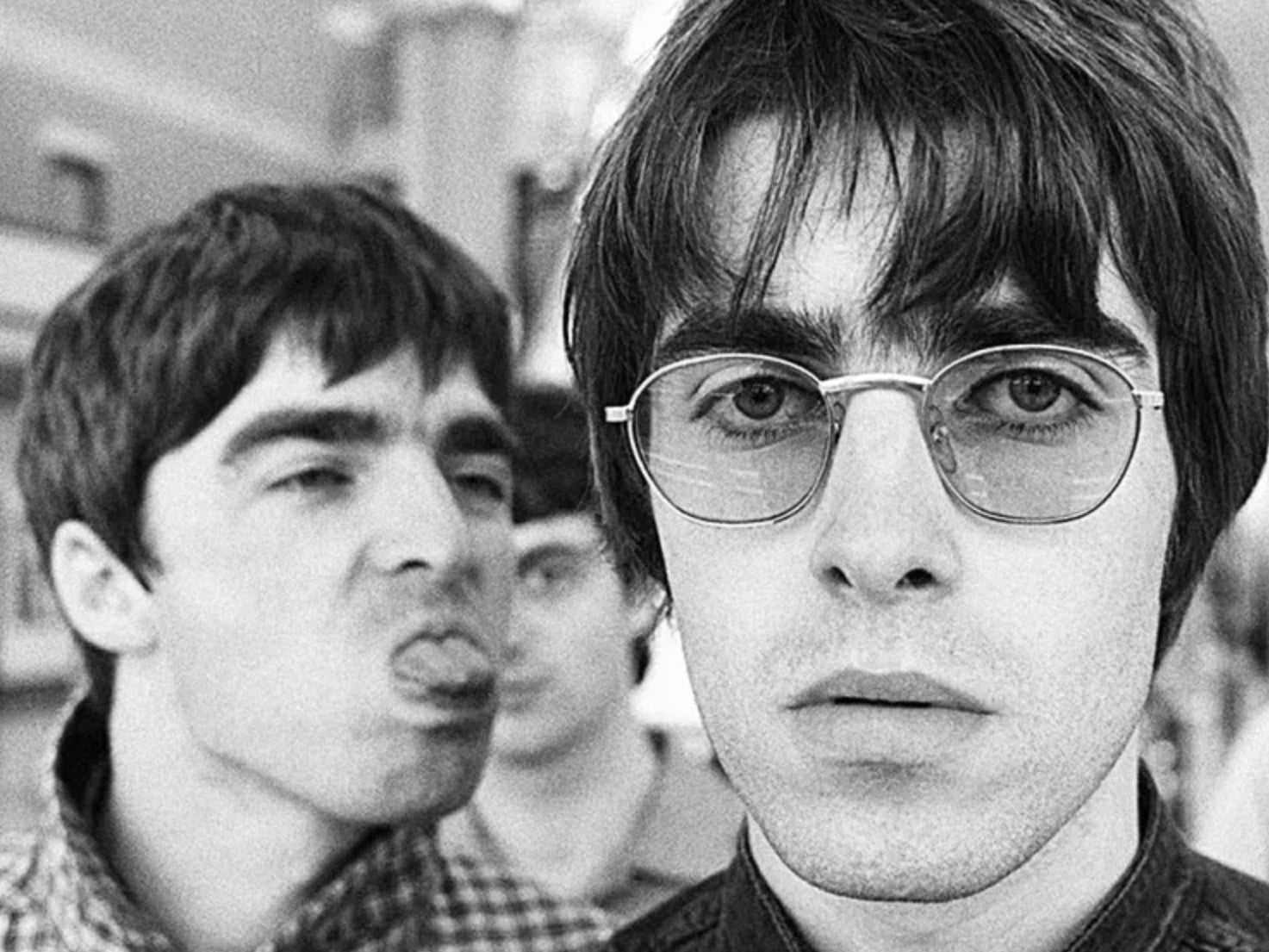

Gallagher, 51, and Squire, 61, go back many years. When the former was a teenager he had posters of Squire’s band, The Stone Roses, on his bedroom wall. He remembers hearing his older brother, Noel, playing “Sally Cinnamon”, and how at school they were the band that everyone began to talk about.

“And then we went to see them,” he remembers. “And it just changed my life. I thought, right, that’s it now, I need to be in a band. And I don’t have to look like the geezer out of The Cure or one of them f***ing geezers out of Guns N’ Roses or Bon Jovi to be in a band. I can actually just do it in these clothes. So that was half of the battle won, you know what I mean? I thought, all I’ve got to do is go up there and sing, and that’ll be me.”

For more than 30 years this has indeed been Gallagher. In the early days, he sang alongside Noel in Oasis, and after 2009, when Noel quit the band – cancelling a festival performance saying he “simply could not go on working with Liam a day longer” – the younger Gallagher simply formed Beady Eye (essentially a rebadged Oasis) then went solo and carried on singing. By his own admission, there was nothing radical about the music he made, but to dismiss it, as many have, as mere meat and potatoes, cagoules and charisma, is to overlook its fundamental romance. Gallagher has the rare ability to articulate a kind of distinct male experience: its pleasure, aspiration, humour, unity, that is undimmed by fad or fashion. As Squire puts it, the appeal of Oasis and then Gallagher’s later projects has lain in “the quality of the songs, the rawness of the recordings, the guitars, the swagger, the irreverence. And the consistency”.

When they finally met, on a street in Monmouth, close to the Welsh studios where The Stone Roses were recording The Second Coming and Oasis were busy making Definitely Maybe, Squire remembers how impressed he was by the fact that Gallagher presented himself “not like a fanboy” but simply as a fellow musician. Today, Gallagher recalls how hard he found keeping it all together in Squire’s presence that day. “The Stone Roses meant a lot,” he says. “And Oasis, when we started, we wanted to be the next best band from Manchester. We’re not giddy, me and our kid, but it was definitely like, ‘Whoa!’”

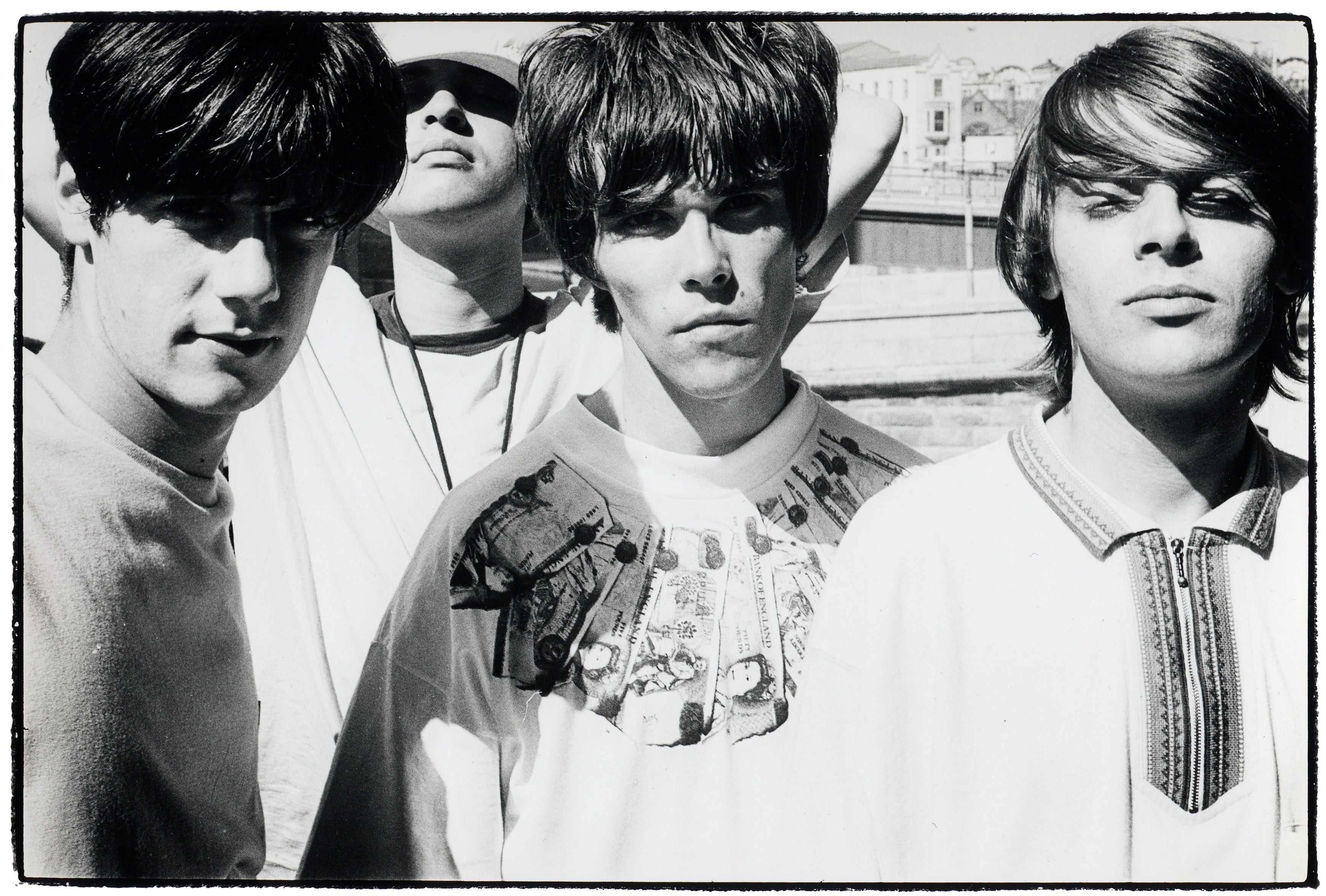

The reverence is understandable. Squire is a towering figure in guitar band history; in the late Eighties and early Nineties, across two hallowed Stone Roses albums, he played with a delicacy and a splendour, a melodicism and a blues-driven heft that helped to define not only the regional sound of Madchester, but a new era of British music.

He is forthcoming about the origins of that sound today – how he picked up the guitar hoping to follow in the footsteps of Mick Jones from The Clash, but without the resources to learn how to play punk rock, he consulted first “a doddery old piano teacher at the end of the road”, and second, “two guitar books by a guy called Harvey Vinson, that had really off-putting hippy covers, but turned out to be great books”. It was in this way that he learnt to play easy blues licks, and where he first saw pictures of The Rolling Stones and Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry. “And I realised when I started learning those riffs that it was kind of like punk but not quite,” he says. “So that’s been in there ever since I started playing: a blues punk epiphany.”

Over the past three decades, Squire’s musical output has been sporadic. The Stone Roses split in 1996. There was a new band, The Seahorses, a couple of solo records, and a Roses reunion, but he was happy making art and playing guitar for his own pleasure. “Family first and everything else around it” is how he describes his life now. “I still can get an easy buzz from playing the guitar without making a record. Same goes for art – I can paint and make things without showing them in public. So I can get that fix and spend time with the kids. I wasn’t crying in the wilderness waiting to be rediscovered.”

Still, when Gallagher invited Squire to join him on stage at Knebworth in the summer of 2022, the experience was markedly different to playing the guitar at home. “It’s probably the difference between dropping a grain of rice into a kitchen sink and a Bikini Atoll test” is how he describes it now. “It was electrifying.”

The idea of collaborating on new material had come up in rehearsals. It seemed a no-brainer to them both. Squire shared some song sketches with Gallagher and then the latter popped round to record them. Not too long after they were flying to Los Angeles to record a full album with Adele and Foo Fighters’ producer Greg Kurstin. The resulting album is a heavyweight record that draws deeply on their shared influences, while still sounding strikingly contemporary.

“You don’t want to be going too retro,” Gallagher explains. “Even though our sound’s classic and that, you’ve still got to sound fresh. At the end of the day we’re here to sell records. If we sell ’em we sell ’em, we’re not going to bend over backwards to f***ing sell a record, but you want it to get on the radio. And you’re only going to get on the radio if you’re sounding kind of in the now.” Still, he’s keen to temper expectations: “There’s no point me over-egging it. If you’re into that type of thing, you’re going to love it. And if you’re into f***ing Bjork, you’ll hate it.”

Speak to Squire about their time in the studio, and he’ll recall the pleasure of it all, and particularly, the valuable contributions from Gallagher. “I remember being really impressed by his ideas for harmonies,” he says. “He just had really nice ideas that he undersold in his way. He pitched his ideas like, ‘Let’s try this s***, it’s probably going to be terrible but f*** it, let’s just go for it.’ And they sounded great and took very little time.”

He was impressed, too, by Gallagher’s vocal takes. “I think he surprised himself. He seemed to quite often criticise himself for being too raw and shouty, second-guessing himself in the studio – ‘Do I sound too lairy on this one? I’m not sure I’m getting there.’ Things like that.” It’s puzzling to Squire that people dismiss the singer as more bombast than musical gift. “He’s not built his career on swagger, has he?” he says. “He’s got immense talent.”

No boozing, no smoking, no nothing, trying to get the lungs back buzzing. Just lock all the doors and stay away from all the f***ing madheads trying to get you to go out

Gallagher himself is more abashed. “My job was to stay out of it as much as possible. And just to go in there and do my thing. They’re the musicians, man, and I’m a singer, so if they can get the music to me in good shape and that, then I can just f***ing overhead kick it in the back of the net, you know what I mean?”

I tell him Squire recalled his input differently, and for a moment he flounders sweetly before admitting he does sometimes make a suggestion or two. “You’ve always got to say the bit,” he says. “But I wouldn’t say it twice. I’d say it once. I always think you should try everything when you’re in there, even if it sounds absurd, because you never know. Not trying ideas, you’re just going to limit yourself. So no matter how mad they are, f***ing try it, and if it’s s***, then it’s only taken five minutes out of your day and then move on.” He thinks of a particularly absurd moment in their sessions. “On ‘Make it Up as You Go Along’, I might’ve been trying to get some sort of mad calypso s*** going on,” he says. “I was going, ‘Without getting the bongos out, we need some f***ing Lilt action.’” He refers here to the Eighties TV advert for the pineapple-and-grapefruit-flavoured fizzy drink that included a distinctive Caribbean jingle. “Obviously it got binned off,” he adds, “which is good.”

Gallagher describes his principal responsibility as “look after myself, and prepare properly and sing the best I can”. This is of course somewhat at odds with the Liam Gallagher of old. For many years he was known for the kind of furious rockstar excess that meant his 2019 admission of taking two grams of cocaine before going on stage felt positively sedate compared to his previous consumption of eight.

These days, he says he is even more serene. Preparing to perform now involves “just getting an early night. No boozing, no smoking, no nothing, trying to get the lungs back buzzing. Just lock all the doors and stay away from all the f***ing madheads trying to get you to go out. Like I say to my kid now who’s starting bands, you’ve got to sacrifice a lot of things. You get one crack at it.”

Over the past 30 years there have been moments where Gallagher failed to sacrifice things. “Obviously there’s been days where I’ve been on stage, and I’ve partied through the night,” he says. “And there’s nothing worse than doing a s*** gig and having to come off stage halfway through because your voice just can’t do it. It’s like f***ing hell on earth.” Wembley, in 2000, was probably his s***est gig, he says. “But I’d just got divorced so there was all that stuff going on. But you’ve got to get to them stages to realise you don’t want it to happen again.” And he is, he reminds me, now in his fifties. “So those days are over, man. It’s got to be early nights. Nice face mask on. And then lots of water and then up early for a bike ride or whatever it is that you do, and then you’ll have a decent time.”

Squire, too, puts great store in taking care of himself. In Los Angeles, Kurstin introduced him to transcendental meditation, which he has found helpful in dealing with the lack of confidence he feels in social situations. “I’m naturally quiet and reserved,” he says. “But I surprised myself by becoming a bit of a gobs***e after doing meditation.”

He has let his practice slide a little lately. “I’m always taking up exercise programmes and new hobbies,” he admits, with the inference that he just as easily sets them down. Still, it was another new regime that led to “Mother Nature’s Song”, which both cite as the album’s most affecting track. “This sounds stupid, but I bought an earthing mat and sat on it and wrote this song,” Squire says cautiously. For those unfamiliar with the world of earthing mats, they are not a musical accessory but a device that looks much like a yoga mat and purports to offer all of the perceived health benefits of standing barefoot on the earth. “I didn’t have anything, didn’t have the lyric, didn’t have an idea for the guitar, I just picked up an acoustic, sat on the mat and wrote that song. I was feeling like I could see a really clear path in front of me. I felt like I’d been tidied up internally.”

The mat was his wife Sophie’s suggestion, he adds. “She’s into all things holistic and herbal, so there’s a lot of earthing mats on YouTube, and I’ve got high blood pressure and I think she heard that it was good for that.” He hasn’t tried it as a songwriting device since. “That was the last song I wrote for the record, but I do combine it with meditation and my blood pressure’s lower than it was.” He pauses. “I feel a bit weird vouching for it.”

All my f***ing olive branches have gone. I’ve got none left

For those listening to the new album, there will be some familiar musical touchstones, not least Gallagher’s distinctive approach to musical phrasing and pronunciation. He tells me how much he enjoyed recording the track “Just Another Rainbow” – “That was the one where it felt like we just put our flag on the moon,” he says. He is aware that some naysayers have mocked the song’s simple refrain, in which he lists the colours of the rainbow. “But I think that’s the best bit,” he says, defiantly. “People need to lighten up, man. And all them great bands used to do that – The Beatles: ‘One two three four five six seven, all good children go to heaven…’ [he nods to the band’s 1969 track ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’] All that. So not a lot of people are paying attention.”

His voice has always sounded designed for certain words – rainbow, and shine among them. Are there particular words he relishes? “I enjoy singing every word,” he says. “I don’t sit there and go, ‘Make sure there’s plenty of f***ing shines in this song. Or send it back and say, ‘Excuse me John, it’s lacking some rainbows.’ I like it all. But I like singing about the weather. It’s a big important thing in people’s lives, isn’t it? It depends whether you get out of bed in the morning. It sets the mood for the day.”

Of course, no conversation with a Gallagher brother is complete without asking about the likelihood of a thawing in fraternal relations, and with it, an Oasis reunion. Since Noel’s divorce from Sara MacDonald last year, rumours of the pair working together again have gathered pace (Liam and MacDonald were not believed to get along well).

Today, Liam is entirely open on the subject of his brother. “Haven’t seen him for ages, man,” he says. “But I think he was at me mam’s the other weekend. He seems to be doing well, man. Seems to be a lot happier in his skin. Surprise sur-f***ing-prise.” Still, he is unlikely to be the one to break the impasse. “Not me, man,” he says. “All my f***ing olive branches have gone. I’ve got none left.” But if Noel were to reach out, he’d be delighted. “One hundred per cent. He’s my brother, I love him.”

Another Roses reunion is also unlikely – in 2019, Squire insisted there would be no further reformations for the band. But I wonder whether we might ever reach enough of a thawing in familial relations to see Noel join Liam and Squire’s collaboration. “It would be amazing, amazing,” Gallagher says, “but I don’t think that’ll happen. I don’t think them two would work well together.” It would be too much, he says. “Too much of too much of too muchness.”

‘Liam Gallagher John Squire’ is out now via Warner Music UK

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments