The real Leonard Bernstein behind Bradley Cooper’s Maestro: ‘A gifted man who drove himself to extremes’

As Bradley Cooper’s bravura Maestro goes up against Oppenheimer and The Zone of Interest at the Oscars, David Benedict dives head-first into the passionate, contradictory, action-packed life of a cultural icon

Although Bradley Cooper is the first person to portray the magisterial Leonard Bernstein on screen, there’s also a pretender to the throne. Almost.

In 1990, Carl Davis, composer of everything from ITV’s epic The World at War to the BBC’s beloved Pride and Prejudice, played the role of conductor in a filmed studio session recording a crossover album with full orchestra and opera divas Lucia Poop and Renata von Trapp. Poop and Trapp were, of course, actually French and Saunders. Their delicious “I Should Be So Lucky” cover version sketch was spoofing Christopher Swann’s famously tense documentary film of the making of an operatic recording of West Side Story in September 1984, a passion project conceived and conducted by its composer, Leonard Bernstein.

Davis wasn’t literally playing the man, but the fact that, 33 years on, the spoof is still so ridiculously effective is testament to the strength of its genesis and Bernstein’s industry clout. His drafting of inappropriate opera singers to record a musical theatre masterpiece is now largely regarded as misguided but, back then, the 66-year-old Bernstein was such a superstar that the notoriously high-minded record label Deutsche Grammophon came on board. In the process, they racked up epic sales. Decades on from that recording session (now back on screen on BBC iPlayer), West Side Story remains the composer’s most recognisable work thanks, partly, to Steven Spielberg’s recent movie remake. Although his new $100m version boasted pleasures including a screenplay by Tony Kushner (of Angels in America fame) and made a star of Ariana DeBose as fiery Anita, it generated more media brouhaha than box-office, which stands in sharp contradiction to the beloved, original 1961 screen version.

The all-dancing, all-singing, thrillingly vital Romeo-and-Juliet-in-New-York-gangland movie of the 1957 stage musical won an eye-widening 10 Oscars, including Best Picture. It’s entirely accurate to say that American airwaves and homes were alive with the sound of Bernstein, since its Grammy-winning, triple-platinum soundtrack was one of the bestselling albums of the decade. It sat at No 1 in the Billboard charts for 54 weeks, the longest run of any album in history, a statistic rivalled only by Michael Jackson’s Thriller. All of which will have done wonders for both Bernstein’s (not small) ego and his bank balance (ditto). What makes it yet more remarkable is that composing was not even really his day job.

Decades before the term was coined, heavy-smoking, high-living Leonard Bernstein, born in 1918, had become a hyphenate. Humphrey Burton (by far the most informed and shrewd of his several biographers) summed him up as “composer, pianist, author, television teacher, Harvard lecturer, cultural icon, humanist and conductor without peer”. Bombastic as that sounds, he wasn’t exaggerating. And not only did Bernstein master each of those disciplines, he was universally regarded as a leading public intellectual and one of America’s most crucial cultural figures. The Leonard Bernstein Letters – 600 fascinating pages culled from tens of thousands of letters – has a cast list spanning everyone from Aaron Copland to Francis Ford Coppola via Lauren Bacall, Frank Sinatra, Ingmar Bergman and Jackie Kennedy. Anyone seeking a who’s who of 20th-century culture need look no further.

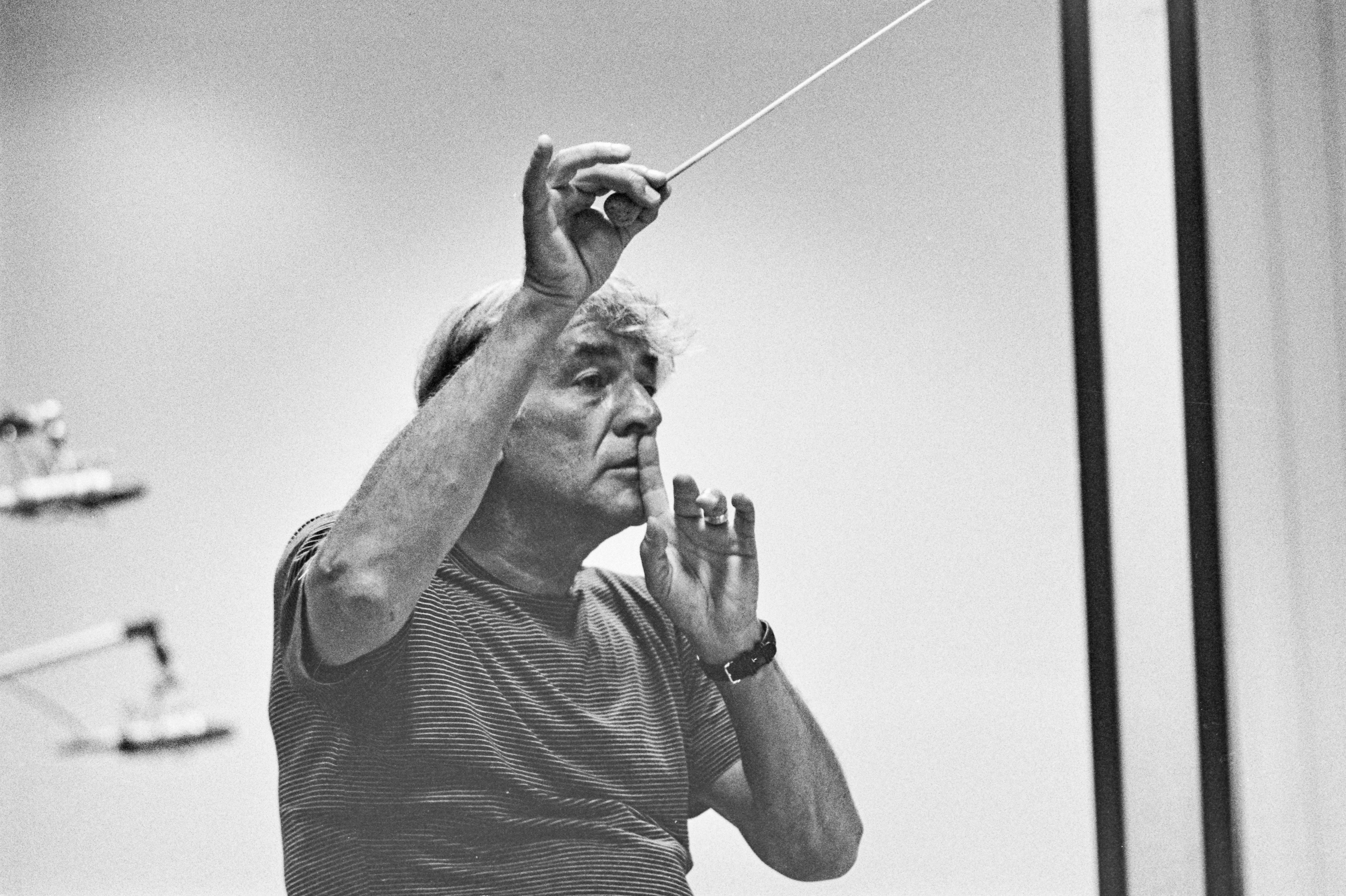

A prodigiously gifted man of omnivorous appetite and heart-on-sleeve energy – his wild conducting style semaphored his passionate feelings about the music he adored – Bernstein drove himself and those in his orbit to extremes and achieved fame at a level these days accorded pretty much solely to movie and pop legends. Not for nothing did the eldest of his three children call her clear-eyed autobiography – one of the many sources of Cooper’s Maestro – Famous Father Girl.

That fame was ignited by a single live broadcast. In 1943, at no notice – and without rehearsal – Bernstein stepped in for the legendary conductor Bruno Walter who had been struck down with flu. The concert was broadcast live from Carnegie Hall across the nation by CBS and, a decade before rock’n’roll took over, it made the front page of the next day’s New York Times. It’s a moment vividly captured in the bravura opening of Maestro where we watch Bernstein leap naked from bed, pausing solely to slap his male lover’s arse, and slide seamlessly into shot as conductor. It’s as splendid as it is surreal and instantly sets the tone for the film’s arrestingly grown-up examination of seriousness and sensuality.

Both of those qualities were in abundance not just in his work but also throughout his chaotic personal life. Although married in 1951 to actress Felicia Montealegre who, according to the deeply researched film, went into the relationship with her eyes wide open, Bernstein simultaneously maintained not just flings but longstanding, highly important relationships with men. At a point where gay sexuality of public figures had to be kept severely private, the necessary deceits and often unnecessary dramas had consequences for all concerned, not least his children Jamie, Alexander and Nina.

But in the public sphere, his dedication to music – there are hours of footage of Bernstein at work showing him not so much making music as devouring it – and his sheer dynamism made him almost outlandishly successful worldwide. Not everyone loved his pushing of musical scores to expressive extremes, but his feverishly passionate advocacy of somewhat neglected composers, most especially the often torrid Gustav Mahler, put them at the top of the cultural agenda.

Without Bernstein, you couldn’t have Sondheim

Yet for all his vast discography of centuries worth of classical repertoire, it’s Bernstein’s work as a composer that most impress the leading British conductor and BBC Proms favourite John Wilson. “This is not to diminish his stature as a conductor,” Wilson says, “but he means even more to me as a composer.”

“He didn’t put pen to paper unless he had an inspired idea, which has ensured his works are played all the time. And he was absolutely front and centre when it came to narrowing the gap between opera and musical theatre. He did for the form what Puccini did for dramatic integration in opera. Every single musical marking in the West Side Story score serves a dramatic purpose. Without Bernstein, you couldn’t have Sondheim.” Wilson is fervent about Bernstein’s musical iconoclasm. “He knocked down so many walls. You can’t underestimate the importance of his genre-crossing and how that helped legitimise certain art forms.” He’s equally passionate about Bernstein’s classical compositions, which he has conducted across Europe and the UK. He points to Chichester Psalms, the utterly distinctive, plangent and punchy choral and orchestral work he wrote to Hebrew texts for Chichester Cathedral in 1965.

“He infused works with distinct personality. And I’m always struck by the tautness of it. And his use of jazz and pop are not token. In many respects, he was a pioneer: Aaron Copland gave us the wide open spaces of America and George Gershwin gave us the sound of Manhattan. Bernstein melds those worlds together and makes them his own.” That blend is gloriously apparent in his movie score for Elia Kazan’s blazingly political On the Waterfront. Bernstein’s score adds savagery, scale and heartbreak and despite winning him an Oscar nomination, he promptly abandoned film because he wanted to write music that stood on its own. Arguably, however, his role as an educator is even greater than that of composer. The reason the almost equally eclectic musician André Previn, one of his most important musical successors, wound up being watched by nearly half the UK population on the 1971 Morecambe and Wise Christmas Show was because Previn had become famous for being on television presenting and talking about classical music. He had consciously followed in Bernstein’s celebrated footsteps.

In January 1958, two weeks after becoming music director of the New York Philharmonic, Bernstein conducted his first televised Young People’s Concert. Over the next 14 years, he introduced an entire generation to classical music with 53 concerts broadcast in more than 40 countries. He later described the massively popular concerts and lectures as “among my favourite, most highly prized activities of my life”. And his six intellectually daring, musically in-depth televised lectures at Harvard in 1973 entitled The Unanswered Question (still available online) remain a riveting masterclass in making arguments about music as language thrillingly accessible.

His avowed “mission” to educate and inspire increasingly blurred lines between culture and politics. In the 1960s he instigated blind auditions at the New York Philharmonic to encourage musicians of colour. The term “radical chic” was invented by Tom Wolfe in 1970 for a cover story in New York Magazine describing a notorious party Leonard and Felicia held at their apartment to raise awareness and funds for the defence of members of the Black Panther movement.

Bernstein’s hallmark mix of passion, politics and music hit its zenith nine months before his death in 1990.

On Christmas Day 1989, Six weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the day after the Brandenburg Gate opened between East and West allowing half a million Berliners to cross back and forth, the 71-year-old Bernstein was in the city. Having personally carved a chunk out of the wall to take home to his family, and lit Hanukkah candles at the city’s oldest synagogue, he conducted a concert climaxing with the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. It’s famously a choral setting of Schiller’s Ode to Joy but for this occasion, Bernstein changed the word “Freude” (joy) to Freiheit: “Freedom”. The idea initially ruffled feathers – why was he messing with a masterpiece? – but the round-the-world broadcast completely vindicated Bernstein’s intervention. Like umpteen cultural moments in his ferociously action-packed life, it was a typically bold gesture that captured and expressed deep truth.

‘Maestro’ is released on Netflix today (20 December)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments