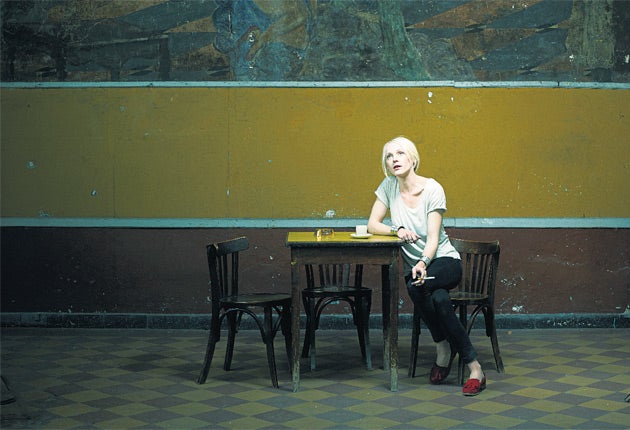

Laura Marling - All hail the Queen of Folk

Laura Marling is the most gifted singer-songwriter working today. And with her third album, she's set for mainstream success, says Andy Gill

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's interesting to note that, in our smart-phoned, kindled, touchscreen-tableted culture, folk music is more popular than it's been in four decades. Sometime over the last five years, a fundamental sea-change in attitude has seen the resurgence of folk music, both in America and Britain. The most striking confirmation of this came at this year's Glastonbury Festival, where Mumford & Sons performed songs from their huge-selling, chart-straddling album.

A few months earlier, at the Brit Awards, the ascendancy of folk music was confirmed by the unexpected success of Laura Marling, prolific young doyenne of the new folk scene, who was anointed British Female Solo Artist in front of a largely bewildered crowd. It was her first big award, after Mercury Prize nominations for her first two albums. But acclaim was only a matter of time in coming: as she readies the release of her third album, A Creature I Don't Know, Marling is clearly the most extravagantly gifted young singer-songwriter operating in Britain today.

Born Laura Beatrice Marling in 1990, the youngest of three sisters, she started playing guitar aged just six, developing an accomplished fingerstyle technique. Raised in the Hampshire village of Eversley, she attended Leighton Park Quaker School, which may account for the quiet reserve which has earned her a reputation for aloofness. Her church roots will be revisited this October during Marling's When The Bell Tolls tour, in which she performs in some of England's most beloved cathedrals.

At 16, Marling was gigging in London and putting her first songs up on MySpace, which quickly led to her being signed to Virgin Records. She lucked into a productive association with a group of young folkie fellow travellers, amongst them Country Winston Marshall of the Mumfords and Charlie Fink of Noah And The Whale, with whom Marling would perform for a while before launching her solo career. She and Fink also began a relationship, and the couple moved with friends into a house in Kew, before the pressures of city life exerted the anxieties which spawned the songs of her debut album Alas, I Cannot Swim, produced by Fink.

Like Dylan, Marling has the magpie tendency to incorporate whatever she's reading or hearing into her songs. Her re-reading of Jane Eyre three times in the months leading up to the recording of her debut not only resulted in the Gothic influence behind songs such as "Night Terror", but surely also contributed to the intense examination of personal relationships, which drew comparisons to Joni Mitchell's Blue. It seemed extraordinary that a 17-year-old should have the maturity to write something as considered as "Ghosts", but Marling was a young voice with an old heart, a quality shared with only a few tyro talents through the years, the rarefied likes of Dylan, Mitchell, Cohen, Simon and Jackson Browne.

Elsewhere on the album, "Shine" reflected the tug in her character between introspection and extroversion. She admitted it's in her nature to feel deeply and read too much into things. Hardly surprising, then, that she should characterise her songwriting technique as "vomiting emotion on to a melody", with the results, on her debut, left relatively unadorned and simple.

The songs on the Ethan Johns-produced follow-up I Speak Because I Can likewise had the stark, thorny simplicity of overgrown briars, though her talent seemed to be growing with the predatory speed of briars, too. Tales streaked with reproach and revenge, such as "Made By Maid" and "Rambling Man", seemed written in the voice of traditional folk ballads.

It was, she explained, an album made by a 20-year-old "feeling the weight of womanhood". Part of that burden may have been occasioned by her break-up with Fink, an event which traumatised him so badly he wrote an entire album, Noah And The Whale's The First Days Of Spring, about it. As she took up with Marcus Mumford, the UK's new folk scene began to resemble the Laurel Canyon scene of the late '60s, with everyone playing on each other's albums, and forming webs of romantic liaisons. (Marling and Mumford have since split amicably).

With A Creature I Don't Know, Marling broadens her range considerably on the album expected to effect her entry into the pop mainstream. "I guess it's similar to the last album, because it's still about strength and weakness, and love and hate," she says. "But there's the idea of convincing yourself of things that you want but don't need, of a constant balancing, and wondering whether you're going to tip over the edge or not." Again produced by Johns, it digs even deeper into the wellspring of emotional turmoil, binding the songs in tendrils of folk-rock guitars, banjos and strings. Miasmic guitar drones underpin the sensual pursuit of "The Beast", while keening siren harmonies attend the emotional disrobings of "Sophia" and "Rest In The Bed".

The Joni Mitchell-esque anatomisations of relationships continue in songs such as "The Muse" and "I Was Just A Card" – Marling has also let a few Joni-style melismatic touches slip into her delivery here and there – while the sombre "Night After Night" clearly bears the epistolary imprint of Leonard Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat". "Someone told me a good writing tip is to write conversations with people you can't have conversations with, that it's quite useful for developing characters," she explains. "I did that a lot while I was writing this album. There's of a lot of one-sided conversations in it." Save for the zither-like jangle of the concluding shanty "All My Rage", it's an album less in thrall to traditional folk forms than its predecessors – the sound of a confident artist boldly heading into pastures new.

This is perhaps surprising in view of Marling's ambivalence regarding the increasingly technological modern world. She may have been signed on the strength of her MySpace, but she harbours misgivings about the effect of modern mass media on culture, believing that "everything is in danger of becoming the same". In a pop era obsessed with superficiality and surfaces, bravado and bling, it's Marling's depth and reserve that most marks her out from her peers, and ensures that her own art runs little risk of blending anonymously into the broader pop scene.

'A Creature I Don't Know' is released on 12 September on Virgin Records. When the Bell Tolls tour from 14 to 29 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments