How do you solve a problem like Korea? The Slovenian rock band who played The Sound of Music in Pyongyang

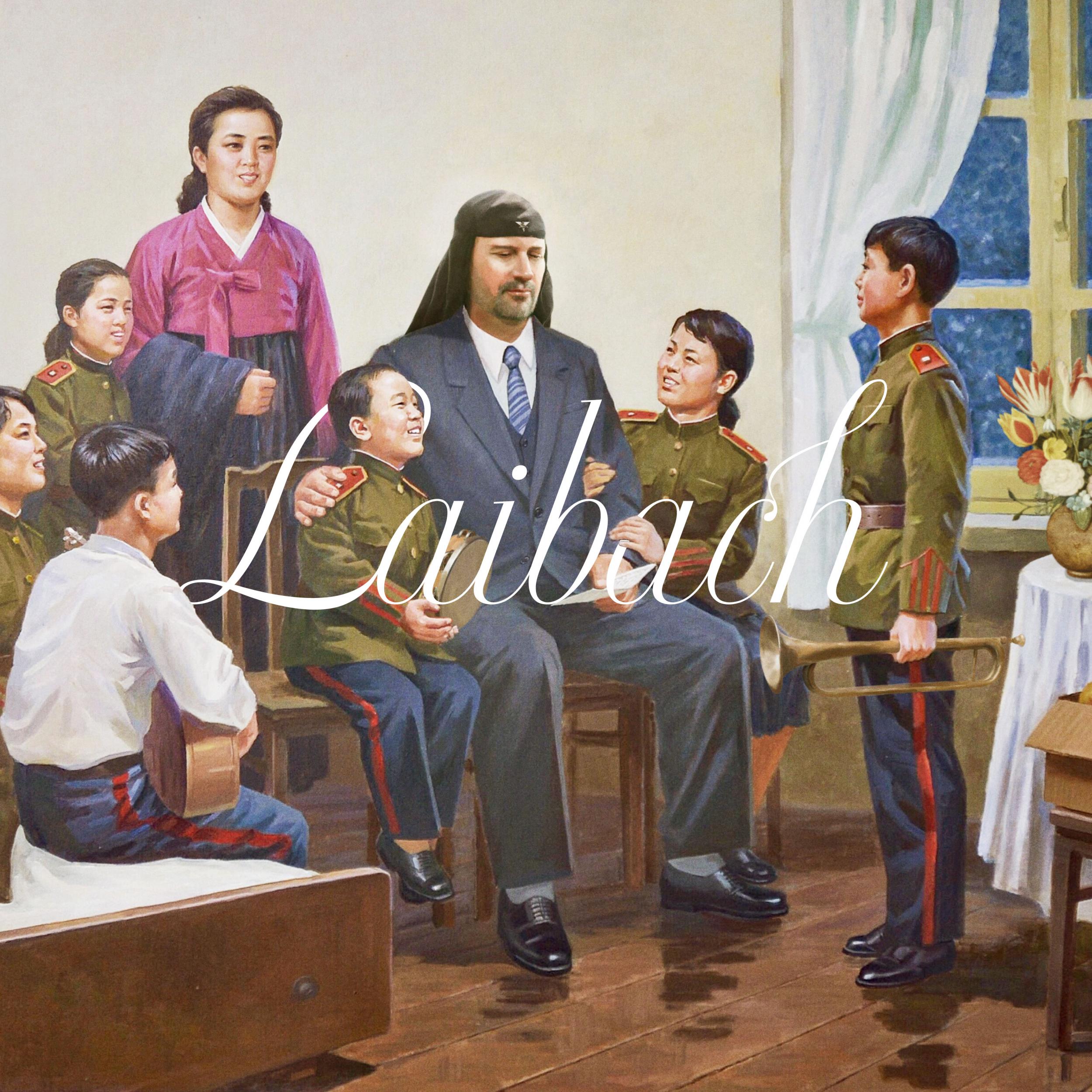

In 2015, Laibach were the first western band to play North Korea, performing covers of songs from the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. Now, they're releasing an album about the trip, writes Alex Marshall

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a recent afternoon, Ivan Novak, a member of the Slovenian rock group Laibach, goes for a walk in the hills overlooking the country’s capital, Ljubljana. In between stops to pet passing dogs, he explains what it was like when Laibach became the first western band to perform in North Korea.

In 2015, the group made headlines around the world – many bemused – when they played a show in the insular, communist country that consisted mostly of over-the-top covers from The Sound of Music.

An album of the same name featuring some of those songs – including “Maria”, reworked to ask, “How do you solve a problem like Korea?” – has just been released as a final document of the trip.

The technical setup for the Pyongyang show, held in a theatre next to the headquarters of North Korea’s secret police, left little to be desired. “There was one plug for everything,” Novak says. “Its cord had to be stuck down with tape so people didn’t trip over it.”

North Korea’s censors turned up during rehearsal to listen and demand changes, he adds. “They kept telling us the songs had to be quicker: ‘Happy tune! Happy tune!’”

Officials also asked if Laibach’s lead singer, Milan Fras, could be dropped from the show, Nokav says, partly because his voice – a deep growl – sounded uncannily like Kim Il-sung, the grandfather of the current ruler Kim Jong Un, singing and might disturb the audience. After negotiation, Fras ended up performing.

“We didn’t mind,” Novak says of the censorship. “They’re very sensitive about music. They want it to always be nice and upbeat.”

Novak continues to recount memories from the tour, making the whole process of playing North Korea sound so enjoyable and interesting that it didn’t sound as if the band had been in one of the world’s most repressive nations.

“Of course it’s a totalitarian country,” Novak says, with a shrug. “But which country is not totalitarian nowadays?”

Laibach was a surprising choice for North Korea. Since forming in 1980 in Trbovlje, a mining town, when the country was part of Yugoslavia, they have been one of Europe’s most provocative bands. They started out playing bombastic industrial music, appearing on stage in old army uniforms and making heavy use of symbols and poses that suggested fascism or extreme nationalism.

Laibach is the German name for Ljubljana, used by occupying German forces and collaborators in the Second World War, and some in 1980s Yugoslavia thought the band were Nazi apologists or right-wing extremists. The authorities banned them from performing under that name.

“In the time of socialism, they almost provoked a revolution,” says Marina Grzinic, a Slovenian philosopher who has written about Laibach since the 1980s. “They wanted to force us to think about our history,” she adds. “It was necessary to be shocking, to shake everything up, to force people to think.”

Alexei Monroe, an academic who has also written extensively about the group, says: “They wanted to explore the relationship between art and totalitarianism.” Laibach used totalitarian symbols, taking them to absurd extremes as a way of mirroring society and showing where it might be headed, he adds.

The band has made albums exploring many different kinds of power, Monroe adds, exercised by everything from nations to corporations, often changing their musical style each time (they have covered “Jesus Christ Superstar” as well as a selection of national anthems).

It wasn’t just in Yugoslavia that Laibach caused confusion. They were equally misunderstood when they first went to the United States. A 1988 review in The New York Times described the band as “either an ugly phenomenon or a didactic joke – and a loud one either way.” (The same review highlighted one song’s lyrics – “Let’s make the United States of America first again” – which now seems 30 years ahead of its time.)

Laibach’s refusal to explain themselves fuelled the misunderstandings. When asked in the 1980s by the German newspaper Die Zeit if they were Nazis, for instance, the band replied in a written statement: “We are Nazis as much as Hitler was an artist.”

They have largely left the explaining to others, such as academics like Monroe and Grzinic. Slavoj Zizek, the Slovenian left-wing philosopher, once wrote: “Laibach does not function as an answer, but as a question.”

Monroe agrees with this. In Slovenia, the band’s politics are widely seen as far-left, he says. But Laibach wants to provoke and perplex. “If there were no uncertainty, it wouldn’t be Laibach anymore,” he says.

“Why should I explain?” says Novak, 60, who officially does “the lights” for the band’s shows but also shapes its music and artistic choices, when asked to talk about Laibach’s motivations. “If you are a poet, you don’t talk about your poems. You don’t say, ‘When I wrote water, I actually meant something completely different.’”

The band has recently gained fans in the alt-right who like their outfits and pomposity, Novak says. He laughs at the idea but refuses to denounce it. “We simply don’t belong to anyone,” he says.

Novak said the band wanted to cover The Sound of Music long before they visited North Korea. Learning that North Koreans love the movie gave them an excuse. “It’s one of the few American films they’re allowed to watch. They learn English with it, apparently,” he says. It was a way of communicating across the cultural and musical divide, he adds.

He denies there was any provocation behind the choice. “Climb Every Mountain”, for instance, was not intended as a call for the North Korean people to rise up, he says. “It’s a purely sexual song,” he adds, before going into a long explanation of the Freudian aspects of The Sound of Music.

“What’s the point in going to North Korea to destroy the system that is going to change by itself anyway, slowly?” Nokav says. “They live a life they believe is the best possible life, most of them.”

If he wanted to provoke anyone with the trip, it was Westerners who are willing to believe anything about North Korea, he adds.

A few hours after the walk, Novak goes to a “Balkan sushi” restaurant in the middle of Ljubljana for dinner. “It’s raw meat, basically,” he says. “I’m a vegetarian, but here I eat meat.”

Novak is joined by other members of the band, including Fras, who spoke in a high-pitched voice, completely different from the rumbling bass of his singing style, and Boris Benko, a singer who also took part in the North Korean trip.

“I thought that by going, we’d learn something about North Korea,” Benko says. “But actually when you go there, you realise you’ll never know anything. Because you’re never sure. Is this real what we’re seeing? Is this staged? You’re always questioning.”

Isn’t that a lot like watching, or meeting, Laibach? Benko laughs, and avoids answering the question.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments