‘We got the power back’: Kwabs and Hardy Caprio on surviving the music industry and childhood trauma

Seven years ago, singer Kwabs was on the cusp of national success, only to walk away from it all. Now with a brand new single, he joins rapper Hardy Caprio to tell Roisin O’Connor how they’ve each navigated major labels, industry frustration and tumultuous upbringings to reclaim their independence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 2015, Kwabs was on the rise. The British artist born Kwabena Sarkodee Adjepong had made the longlist on the BBC’s Sound Of poll, alongside Stormzy, Years & Years and Wolf Alice. An early cover of James Blake’s “The Wilhelm Scream” helped secure a record deal with Atlantic; heavyweights including Ed Sheeran, Sam Smith, Coldplay, Kylie Minogue and Laura Mvula sang his praises on social media. His hit single “Walk” featured on the Fifa 15 soundtrack and, in a review of his debut album Love + War, The Independent’s late critic Andy Gill praised the “warm, intensely human timbre” of Kwabs’s voice. He was poised for the kind of success that most artists only dream of. Then everything went quiet.

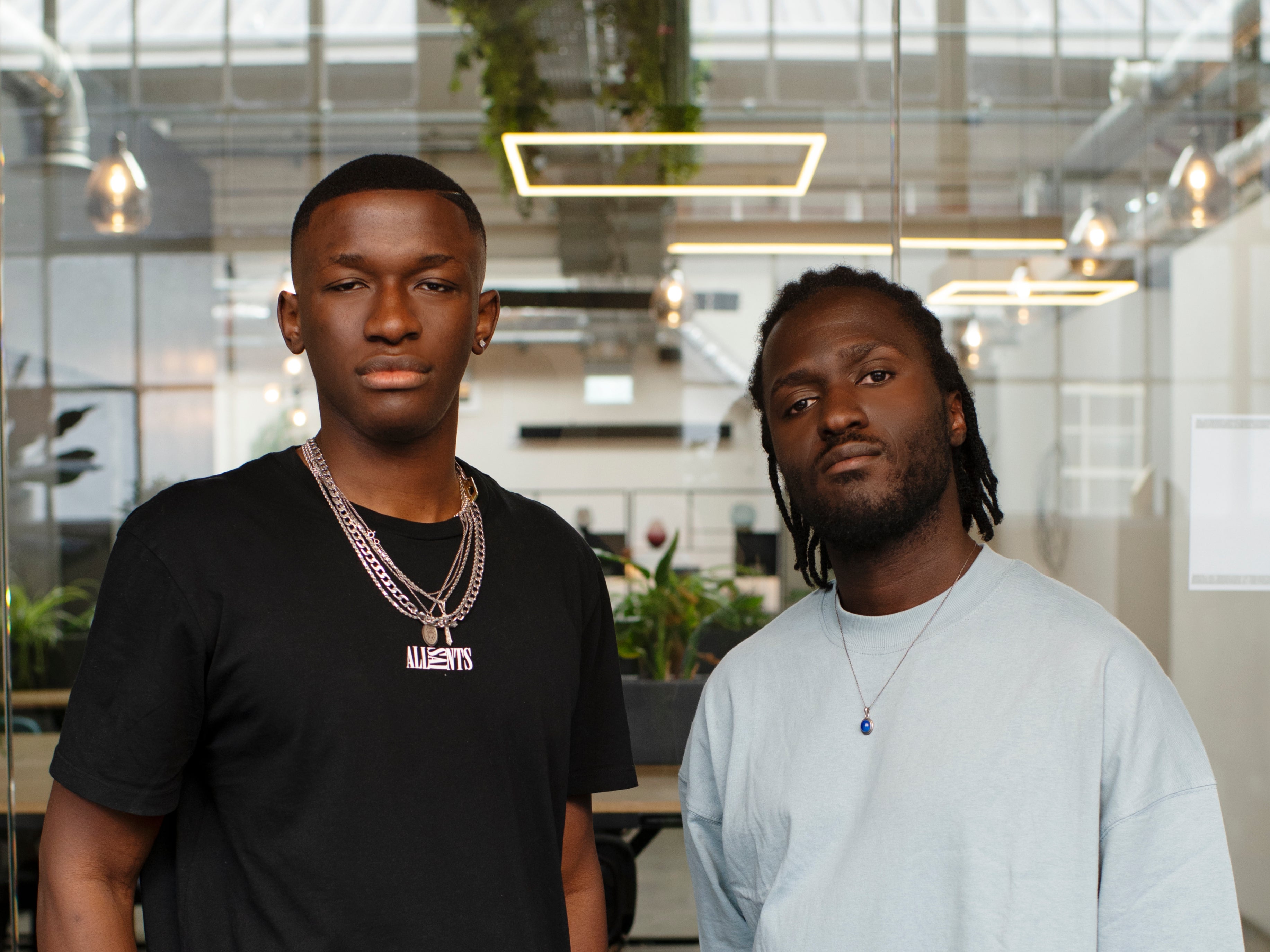

“By the time it got to 2016, I was tired,” Kwabs tells me. He draws a breath and repeats the word, drawing it out for emphasis: “Tiiiiiiired.” We’re sitting in the glass-walled meeting room of rapper Hardy Caprio’s west London studio. Kwabs and Hardy are next to one another, having their photo taken. Hardy’s dressed in a black AllSaints shirt and jeans; a diamond stud glints from his left earlobe. Kwabs is wearing a loose-fitting blue T-shirt and green corduroy trousers. They’re relaxed, voluble; you wouldn’t guess they’ve only met once before. I wanted them to have a chance to talk alone, because the topics on the table today would be tricky to discuss in front of one stranger, let alone two.

About a week before Kwabs announced his first solo single in seven years, Hardy shared a statement on Twitter. It was titled “Being in the industry has broken me” and it was a heartbreaking rumination on fame, childhood abuse, and an industry that has a track record of both exploiting and neglecting young Black artists. “Something that was once my therapy, my passion, became my torment and my anguish,” the 26-year-old wrote. Fans were shocked to hear this from an artist known for his boyish, cheeky swagger. But for Kwabs, it sounded all too familiar.

“I just wanted to see what was inside your head,” Kwabs, 32, tells Hardy. They listen to one another attentively, nodding or making soft exclamations if an anecdote strikes a particular chord. “Beyond [my] Instagram post saying I’ve been away because I’ve not been OK, I didn’t put much detail in it. But I found your post remarkable because of the detail and the bravery required. So I wanted to get a mutual understanding of where we were both coming from.” For Hardy’s part, he was struck by Kwabs’s ability “to walk away, for yourself. I think a lot of people fetishise this ‘go through the pain’ thing,” he says. “But you don’t wanna be Van Gogh and cut off your own ear.” Kwabs chuckles at the reference: “I have zero interest in that.”

When Kwabs took his first steps in the music industry, he’d already overworked his voice. And Kwabs is his voice: a rich, soulful baritone honed by a stint with the National Youth Jazz Orchestra and studying at the Royal Academy of Music. “I spent pretty much every weekend gigging, which was great for me, living in London… but by the time I had anyone sniffing around me, labels or anything like that, I was tired,” he says. “My voice is more than what I show to other people, it’s self-soothing. I don’t do it now because I’ve worn out the habit, but back then I used to sing through meetings, without even thinking, like a tic. So it [meant] more than the industry had to offer me.” He believes he was actually signed when his voice was at its weakest: “It wasn’t painful, it was just difficult.” He had scans, tests… “apparently it was fine, but I knew it wasn’t fine.” It didn’t get any better, but Kwabs just sang through it, causing himself a lot of discomfort in the process. “It was almost like I was doing it to prove I wasn’t giving up, so when I eventually did, no one could say I didn’t work hard.”

Then, at a certain point, it got to be too much: “I stopped trying to be the biggest, baddest singer on the planet, and once that happened, the vulnerabilities in my voice started to show.” All he was doing, Kwabs explains, was taking his foot off the gas – singing on a softer level rather than belting it out all the time. “There’s a low-key epidemic of artists hurting their voices. But people were saying, ‘Oh, you’re not singing like you’re used to.’ And the industry didn’t really want anything to do with that.”

Hardy dealt with a similar situation of wanting to pare things back – at least to try something different – claiming he was rebuffed by his label and told to do more of the same. Born Hardy Tayyib-Bah in Sierra Leone, he relocated with his family to Germany when he was four, then to Croydon (just half an hour away from Kwabs’s childhood home in Bermondsey, south London). His first foray into music was filming himself and his mates rapping on their phones in the school playground. “I was the worst,” he says in his low murmur, flashing a grin. “I was bad! But I could laugh at myself. I’d just go and improve.” Then he turned 18 and decided he wanted to come up with a proper plan. “I’m actually smart,” he says, wary of misconceptions. “Academically smart.” As if to prove this, he went and got himself a first-class degree in accounting and finance from Brunel University. During that year, he also self-released 30 music videos and spent his weekends in the studio, arriving home at 5am then heading off to lectures. “I’d say whatever was on my mind and throw it out,” he says of those early tracks.

It was one of these videos – a freestyle over Tinie Tempah’s 2007 single “Wifey” dubbed “Wifey Riddim” – that brought him greater recognition, plus a record deal with Virgin EMI. In contrast to Tinie’s playful tribute to his paramour, Hardy took his audience through a stark portrait of his journey to date, one that demanded hard graft: “Never been perfect but hand on my heart I tried/ But somebody lied/ Maybe it’s TV programmes, will they ever show man/ Life ain’t how it’s described.” He’d wanted to take something beautiful, in this case the hypnotic “Wifey” melody, and give it an edge. “That applies to my whole ‘dance in the rain’ persona,” he says. “The maddest thing is I can hear my soul coming out [in the freestyle]. I probably was mentally scarred at that point but I didn’t understand it.”

Where Kwabs found himself feeling increasingly alienated from his audience and the music he was making, lacking in creative control, Hardy grew frustrated by what he perceived to be efforts to keep him in his lane. “We’re almost like jesters in the castle,” he says of the artist-major label relationship. “I wanted to be consistent. But that naturally goes against the label ethos – they were like, ‘Wait, let’s release one more single.’ Trying to turn me into a caricature. But I wanted to be an album artist.” Weeks turned into months. Hardy never did release a studio album with the label, despite a string of Gold and Platinum-certified singles including 2018’s sun-drenched “Best Life” with Tottenham-born artist One Acen. Now he’s back to being independent. “Yeah,” he grins. “I’m free!”

For Kwabs, also now an independent artist, music is a form of a catharsis – even if the songs themselves are darker in theme. Love + War was plagued by self-doubt, of glancing back over his shoulder at unnamed tormentors, or else reflecting on absent father figures. Songs such as “Fight for Love” melded gospel, soul and R&B influences with Eighties disco and electro-pop; “Perfect Ruin” was a sweet lament in minor piano chords. It was his secondary school teacher, Xanthe Sarr, who recognised his potential and helped get him into “gifted and talented” programmes, opportunities he’d previously not known existed. “That was a big deal, coming from the background I did,” he says. “There’s a reason these places aren’t super diverse. It takes someone like her coming along and being like, ‘You know you could go here?’ It’s pretty pivotal.”

His comeback single, “Hurt a Little”, is a plea for patience and understanding. It opens with tender guitar notes, drifting slowly like autumn leaves to frost-covered ground. “I’m changing a little,” he sings, deep and weary. “I just need some time/ To hurt a little/ Help me ease my mind.” For Kwabs – whose fraught childhood saw him and his younger sister placed in foster care when he was 11 – the song could just as easily be about the wounds in a parent-child relationship as a romantic one. In a 2015 interview, he spoke of “rediscovering” his relationship with his mother in his twenties, when he felt as ready as he could be to try to understand her perspective. “I probably talked to you more than I have to anyone else,” he tells Hardy, explaining that those formative years shaped the direction his music took.

“[Foster] care was my release from the crazy stuff that happened before,” he continues. “It wasn’t a hideous time afterwards but most of what comes out of me, lyrically, as a human being, is trauma from the age of 0-11. All of my songs are basically about poor emotional attachments.” He pauses. “You’ve heard of attachment theory? I’m avoidant.”

“Oh, you lot are stressful,” Hardy interjects, surprising Kwabs into a burst of laughter. “Yeah,” the singer agrees. “I don’t like anyone, but I want human connection at the same time. It’s a mess.”

In his Twitter post, Hardy briefly alluded to being sexually abused as a child for the first time. It was only last year, during a bad trip from an edible (a cannabis-infused snack), that this trauma resurfaced. In a recent interview with the HC podcast, he said he actually called his alleged abuser to confront him about it. “There’s a big change, a pivotal moment in me becoming Hardy Caprio,” he says now. “I forgot most of it, growing up. I became very… flamboyant, there was a lot of bravado and acting like I didn’t care about anything.” He says he now remembers a lot of what happened but was initially “second-guessing” his behaviour – the fact he never felt truly comfortable around other men – because those memories were being suppressed.

“I couldn’t completely stand boldly in who I wanted to be,” he says, “so it was like everyone else’s insecurities were my insecurities. It forced me to look at myself, hard. And that cracked open the seal. I’m grateful it happened because that allowed me to go into the next chapter of my life.” He feels more emotionally in tune with people in general, now. “Growing up, I never heard a rapper talking about what I’ve been through, and that made me feel quite isolated,” he says. “So I was like, you know what, take [my story].”

Prolific as ever, he’s got a cluster of new releases on the way, along with recent singles “Get to Know” – a little darker, more menacing than his usual style, with Ayo Beatz – and the boisterous “Under the Sun”, inflected with luscious electric guitar twangs and Caribbean steel drums. These songs seem to reflect his desire to show all facets of himself to his fans: “I wanted to do one rap, a Croydon release,” he says. “Then something that was more old-school grime. And I like pop music, so I wanted to try something more melodic.”

Growing up, I never heard a rapper talking about what I’ve been through, and that made me feel quite isolated

From his own sparse set of early releases, Kwabs appears to have taken on something closer to Hardy’s mentality. “I’m at the point now where I’m less worried about what impact [putting out music] has on my identity,” he says. “I’m just happy to put something out.” He has no idea if he’ll share a follow-up to “Hurt a Little” anytime soon. “But it makes me happy, and the whole point of me pausing everything was because I wanted to be happy. I had no interest in marrying misery. I did that – I grew up with it – and I have no interest in revisiting it. So now I feel trepidatious, but also relaxed for whatever the outcome is.”

“This is the best form of happiness I’ve felt,” Hardy says. “It’s not euphoric, it’s rational. Now I know I’m doing everything from the right place, and nothing is controlling my emotions except me. It allows me to enjoy the process and know what I’m doing it for.” He glances at Kwabs and they share a smile. “I’ve got the power back.”

‘Hurt a Little’ by Kwabs and ‘Get to Know’ by Hardy Caprio with Ayo Beatz are both out now