Inside Nirvana’s last ever show: Kurt Cobain and a prophetic declaration

Thirty years ago, one of the world’s most visceral bands unknowingly took the stage in a repurposed German airport hangar to play their last ever show. Mark Beaumont looks back at that storied night and its devastating aftermath to uncover exactly what made Nirvana gigs so transformative

It was during a power outage midway through a growling, uneasy “Come As You Are” that bassist Krist Novoselic stepped up to the microphone and, trying to fill dead air with some throwaway chatter, made a chillingly prophetic prediction. “We’re on our way out,” he told the 3,000 people in the crowd, joking that their next album would be a hip-hop record. “Grunge is dead. Nirvana’s over.”

By all accounts, 1 March 1994 at the Terminal 1 in Munich had been an inauspicious sort of gig. As the name suggests, the since-shut venue was a repurposed airport hangar with the acoustics of Somerset’s Wookey Hole. Frontman Kurt Cobain, struggling with a hardcore heroin addiction and growing paler by the show, powered through the gig’s final song “Heart-Shaped Box”, having to fight for the high notes. Though they’d found time for covers of The Cars’ “My Best Friend’s Girl” and David Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World”, the band left the stage for the last time, not even having played their most iconic hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit”.

Novoselic’s tongue-in-cheek words soon rang tragically true. The following day Cobain was diagnosed with severe laryngitis and bronchitis – an ailment he’d battled all his life – and, cancelling all remaining shows, he flew to Rome for treatment. On 4 March, he slipped into a coma after overdosing on champagne and Rohypnol in what his wife, Courtney Love, would describe as his first suicide attempt. He recovered and briefly entered rehab in Los Angeles, but only a month later, on 8 April, was found dead at his Seattle home by his own hand: grunge’s ultimate tortured icon lost at 27.

His manager Danny Goldberg, author of the 2019 book Serving the Servant, was among the group of friends and associates who staged an intervention at the Seattle house in the last weeks of Cobain’s life. “He was in a bad way,” Goldberg told The Independent in 2019. “I spoke to him on the phone when I got home and talked to him one last time. I couldn’t shake him out of being depressed, I couldn’t cheer him up or get him to feel there was hope.”

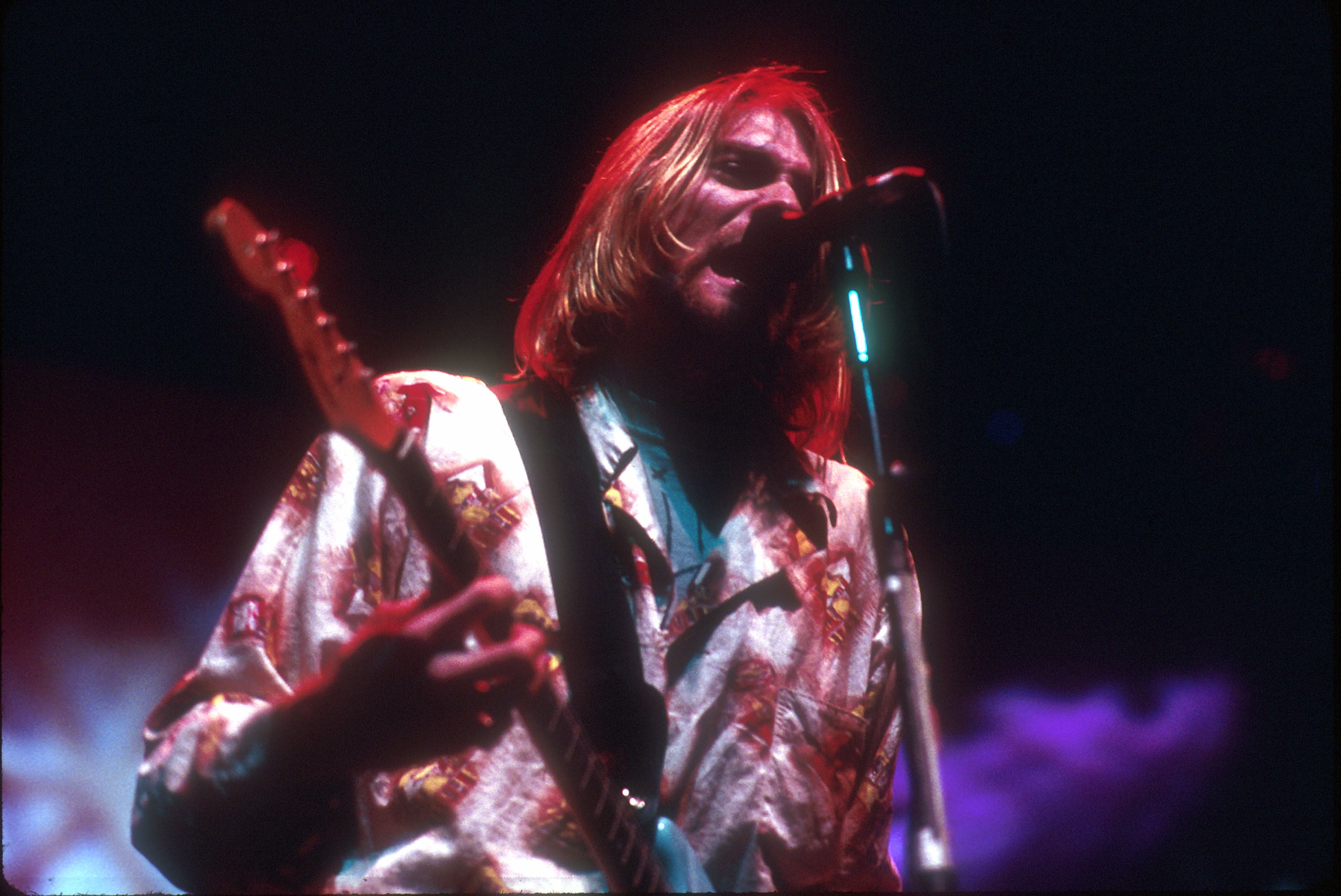

In Cobain, the world lost not just one of its most talented rock stars but, with him, one of its most visceral, energising live bands. Many shows in Nirvana’s brief seven-year existence were true rock’n’roll riots: scenes of wild, cathartic release – not only for the punk and rock fans enthralled by Cobain’s pain-wracked strain of melodic grunge but also the band themselves, who attacked every set as if fighting their way out of a tumble dryer.

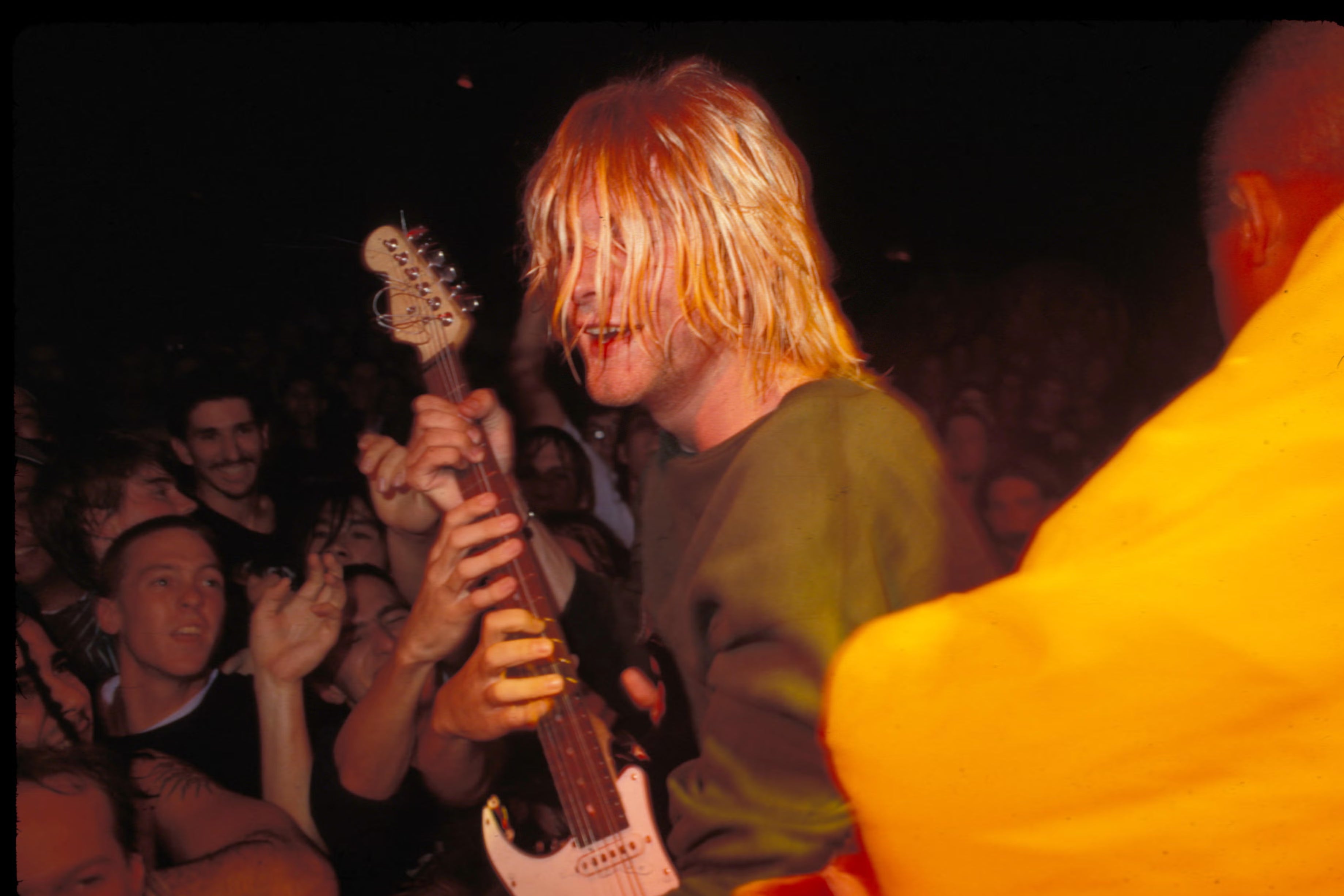

“They didn’t care much if they missed a note or chorus,” says photographer Charles Peterson, who toured with Nirvana throughout their career, and documented much of Seattle’s early grunge scene in pictures – many of which feature in his new art book Charles Peterson’s Nirvana. “That wasn’t the intention, playing these perfect, perfect songs. And so it really allowed Kurt to jump and roll around on the stage, throw himself in the audience and do whatever he felt like he needed to do.”

Peterson’s book brilliantly captures the dervish that Cobain unleashed onstage – and the chaos he inspired doing so. He’s pictured playing guitar while spinning on his head, falling through drum kits and crowd-surfing mid-solo, while fans make daredevil leaps from the top of speaker stacks. Peterson remembers one particularly feral show at Seattle’s Motorsports Garage in September 1990, a year after the release of their debut album Bleach.

“It was just epic,” he says, “almost like a [Pieter] Bruegel painting or something. There was the band and they’re surrounded by people to the sides of the stage. Stage divers left and right running past them and jumping off, almost to the point where Kurt had to grab them and stop them after a while, like, ‘Let us play!’ It was such an insane mass of people. And that was the first time that it really, really went that crazy.”

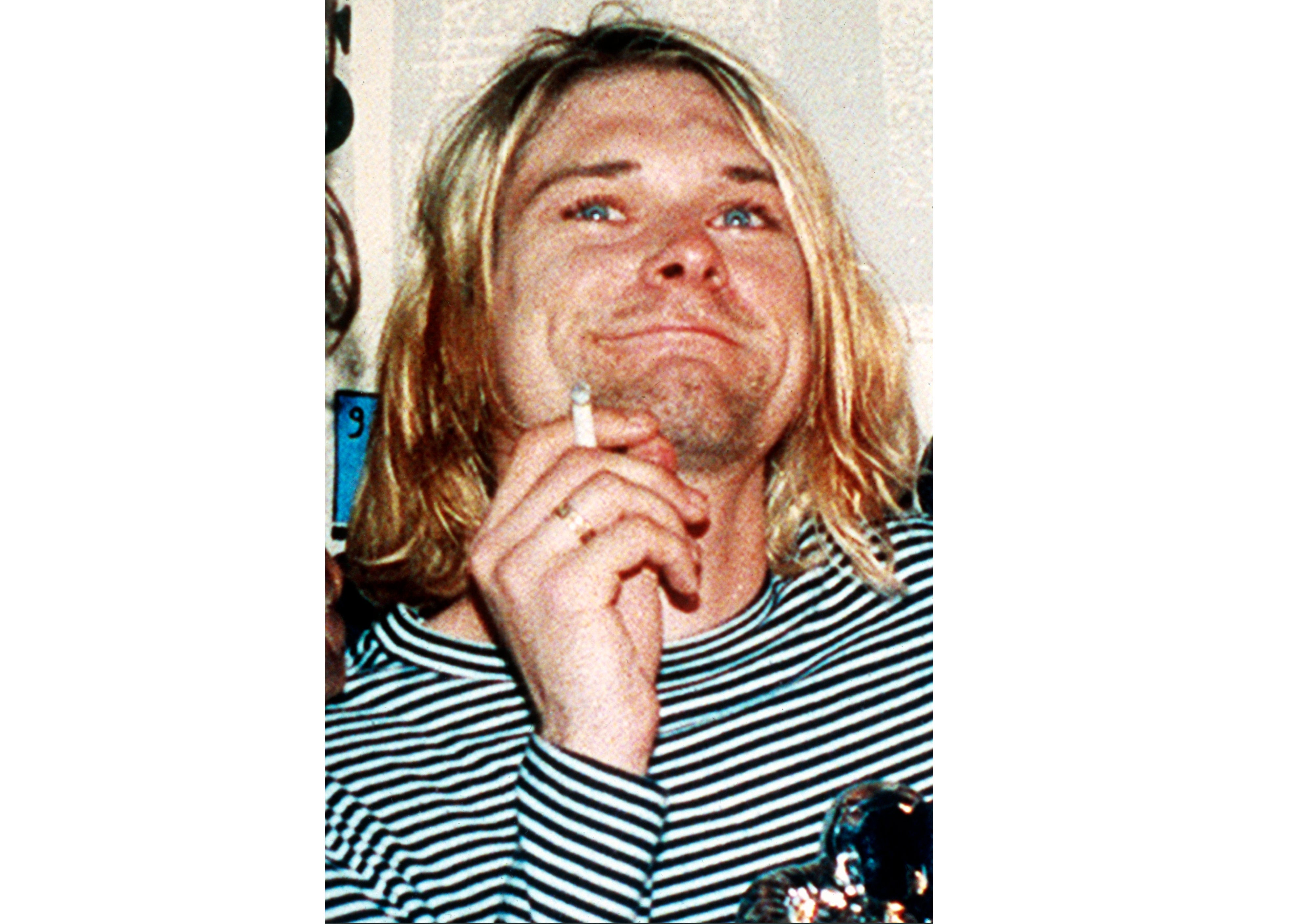

It wasn’t always thus. Peterson recalls Nirvana’s first Seattle show, circa 1988, as a restrained affair. “They just stood on stage in dark lights,” he says. “Kurt was a somewhat of a shy, introverted person. And then I think that with enough practice, he realised, ‘Oh, the stage is mine, and I can do whatever I want with it and myself when I’m on that stage.’ I think it gave him a freedom he might not have had in the other aspects of his life.”

Those early Nirvana shows, Peterson feels, were experienced by fans as deeply communal and endlessly relatable – largely due to the blank emotional page of Cobain’s writing. “With Kurt and his lyricism, it was what I call transmutational, and the music too,” he says. “It could just be about anything that you wanted. You could take it on, and it could make you happy, sad, mad whatever, in that moment, the same song. So when they played live, it was almost like a sublime release that the audience could experience because they could really just make it about whatever was going on within themselves.”

“It’s that combination of darkness, idealism, humour, compassion, cynicism,” Goldberg said. “The totality of it connected so intimately with fans they felt that they weren’t the only crazy people, somehow there were these [musicians] that were popular that understood them. That was his gift.”

UK viewers got their first glimpse of the wildmen within when Nirvana appeared on Channel 4’s flagship youth TV show The Word in 1991. Their performance began with Cobain declaring his future wife Courtney Love “the best f*** in the world” and ended in a squealing pile-up as the studio mosh pit of flailing grunge-heads invaded the stage while Cobain repeatedly screamed “Roger Taylor!” at the top of his lungs. It was a genuine next-gen televisual punk explosion; “Smells Like Teen Spirit” charted at No 7 the following week.

Almost immediately, though, we got an insight into the frustrations that overwhelmed Nirvana in the immediate aftermath of the song’s success. On Top of the Pops two weeks later, the band protested the show’s miming rules and sabotaged their performance of “…Teen Spirit” by barely even pretending to play their instruments. Cobain, who had at least wrangled producers into letting him sing for real, delivered the entire track in a baritone impression of Morrissey.

He took the anguish he was feeling and the unresolved issues about custody of his daughter and the embarrassment of the way he and Courtney had been depicted and turned it into this performance art

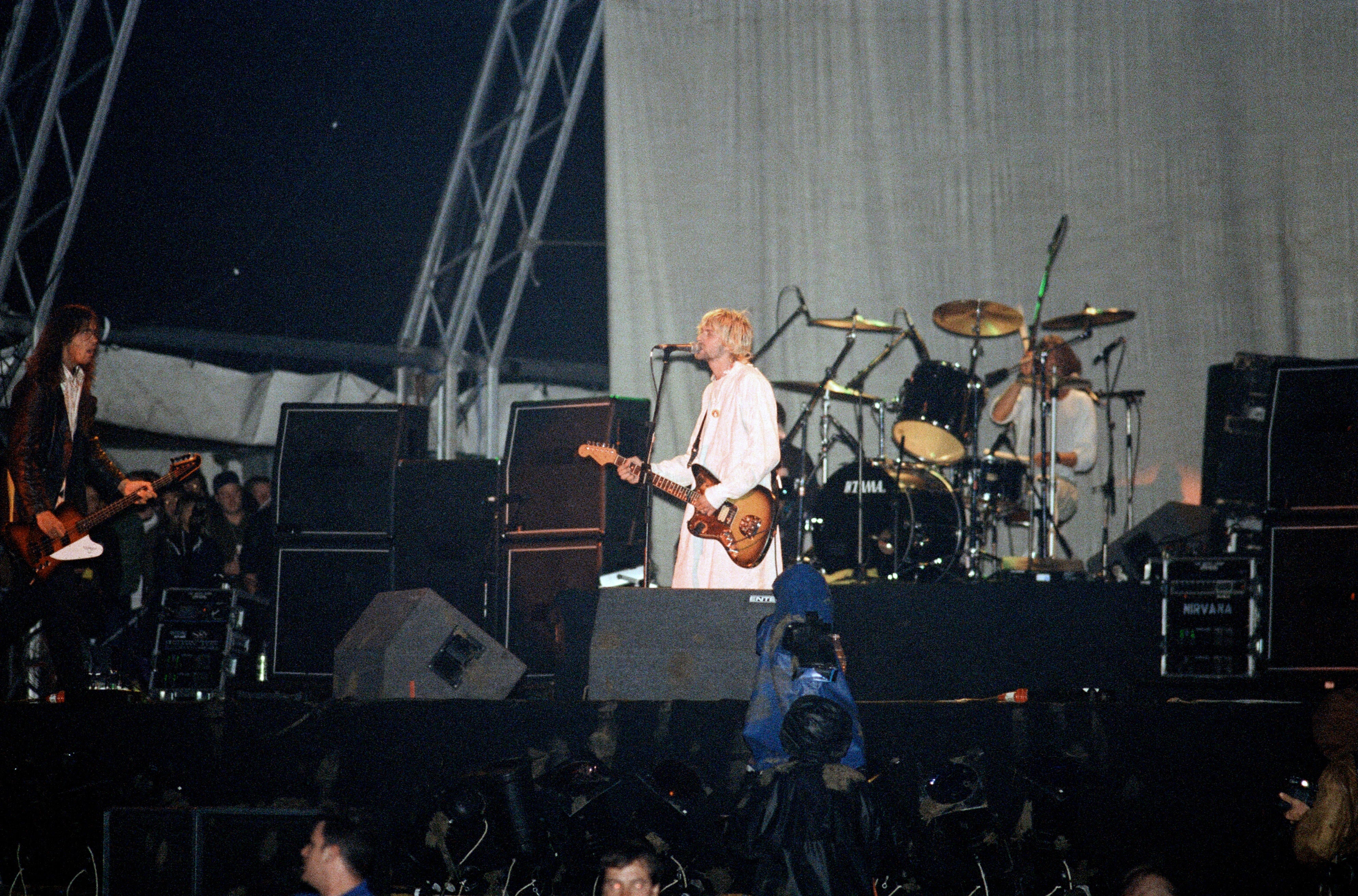

Behind-the-scenes turmoil would continue to spill onto the stage from that point on. When banned from performing In Utero’s most controversial track “Rape Me” at the 1992 MTV Video Music Awards, Cobain defiantly sang its opening bars before launching into “Lithium”. And at the height of the tabloid demonisation of Cobain and Love over Vanity Fair allegations that Love had used drugs while pregnant with their daughter Frances Bean (and the subsequent custody battle), Cobain mocked speculation over his physical and mental health when he was pushed onstage to headline Reading 1992 in a wheelchair wearing a hospital gown.

“He took the anguish he was feeling and the unresolved issues about custody of his daughter and the embarrassment of the way he and Courtney had been depicted and turned it into this performance art,” Goldberg said. Leaping from the chair, Cobain went on to perform one of the most blazing shows of Nirvana’s career, climaxing with the singer throwing his guitar repeatedly into a tower he’d built out of Dave Grohl’s drum kit.

As heroin took a stronger hold of Cobain and fame increasingly devoured his creativity, Peterson feels that Nirvana’s shows lost their spark. “I didn’t find it as exhilarating or enjoyable,” Peterson says. “I somewhat mockingly call the In Utero tour ‘Nirvana with props’. They played some great shows, but the innocence was lost.” The band camaraderie, he adds, seemed to be dissolving, too. “Separate tour buses, and from what I’ve been told, from ’93 on or even late ’92, very little backstage interaction with the members,” Peterson says. “Dave is just a rock’n’roll machine that could probably tour every day of his life and it not be a hassle – but I think for Kurt, especially, having a drug habit, it was a difficult ride having to do all that.”

That final show in Munich, while still electric, saw a band noticeably diminished by their issues: an almighty bang going out with a relative whimper. They hadn’t known it was their last show, but Peterson believes Nirvana were probably beyond saving by that point anyway. “[Cobain had] such a big drug habit that it would be very difficult for them to carry on in the same way that they had been, in my opinion, unless he had gotten help,” he says.

Ultimately, it was perhaps the sense of soul-baring public exorcism in Nirvana’s performances – the way Cobain poured his pain into every show in hope of wrestling it loose – that made them so exhilarating to watch. There was real honesty in their anguish, visceral desperation in their rage. “They could have gotten the drama together and become another Pearl Jam or something,” Peterson considers. “But maybe all that drama was part of it, too.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks