How King Crimson’s masterpiece led a generation to Pink Floyd’s ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’

‘In the Court of the Crimson King’ was released 50 years ago – Pink Floyd, Yes and Genesis could never have sounded like they did without it, says Simon Hardeman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An improvised crumhorn solo in a madrigal in 15/8 time inspired by the dream of a minor character from Lord of the Rings? It could only happen in prog-rock. But it didn’t start out that way.

Fifty years ago in London, everyone who was anyone in music was talking about an extraordinary new band blowing everyone else off stage. They hadn’t released an album yet but had played their ground-breaking mix of rock, jazz, classical and psychedelia in storming live sets. One was in front of maybe half a million people, supporting the Rolling Stones at their free concert in Hyde Park, and another reportedly prompted audience-member Jimi Hendrix to call them the best band in the world. Music magazines – bibles for fans in pre-digital time – had splashed features on them, and labels were competing for their signatures.

The band was King Crimson and the album was In the Court of the Crimson King, released 50 years ago this month. Like Nirvana’s Nevermind, Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and Run DMC’s eponymous debut, it was genre-defining. Its five numbers were by turns pastoral, heavy, whimsical, even easy, beginning with an apocalyptic riff and shredded vocal before careering through a bucket-load of influences from hard rock to classical and modern jazz to the Middle Ages, and ending with an epic title-track.

“It was a game-changer,” King Crimson founder-member and co-writer of every track on the album, Ian McDonald, tells me. “I remember listening back to it and thinking, ‘What is this?’. Bands went back to the drawing board when they heard it – I know when Yes heard it they did.”

This may not have been an entirely good thing. Just four years later Yes toured their No 1 album Tales from Topographic Oceans, a single composition split over four sides of vinyl and inspired by a footnote in the autobiography of an Indian mystic, on a stage designed by a fantasy artist featuring glass-fibre pods that at one gig failed to open, trapping the bassist. They played at such length that keyboard player Rick Wakeman had a curry delivered onstage and ate it while the other members noodled away.

But that could hardly have been predicted when In the Court of the Crimson King landed. “We never thought of it as prog-rock,” says McDonald, who played the flute, saxophone, and keyboards. “It makes me laugh. That term wasn’t being used. We were just doing what we felt the music warranted.”

King Crimson wasn’t the only British band jettisoning the blues element from rock and aspiring to the complexity and virtuosity of classical music and serious jazz in 1969. That September Deep Purple would play their Concerto for Group and Orchestra with the Royal Philharmonic at the Albert Hall; landmark albums by The Moody Blues, Procol Harum, Genesis, Yes, Pink Floyd and others were released; and future prog-rock royalty Wishbone Ash, Hawkwind and Supertramp all formed. But In the Court of the Crimson King was the watershed moment, “an uncanny masterpiece”, according to The Who’s Pete Townshend.

The group were led by guitar wizard Robert Fripp, a master of unusual tunings and complex chords and voicings, says McDonald. Fripp is the one constant in King Crimson over 50 years. He also provided that sustained feedback guitar wail on David Bowie’s “Heroes”. Bassist and lead vocalist was Greg Lake, who would go on to mega-proggers Emerson Lake and Palmer. McDonald, who would co-found late-1970s AOR giants Foreigner (“I Want to Know What Love Is”) brought a range of influences – “army bandsman, male voice choir, jazz trio…”. A flute solo he played on the title track “was a direct nod to [Rimsky-Korsakov’s] Scheherazade”, and he also played the Mellotron, an early sampling keyboard The Beatles had used, recording it through a Marshall stack to get an “enormous” sound.

Poet Peter Sinfield’s lyrics unwittingly set a template for much of prog, admits McDonald: “Some of them were medieval-sounding. Unfortunately, that has meant people have thought progressive rock requires dragons and fairies.” Sinfield went on to write for Buck’s Fizz. It’s hard to know which is the more regrettable.

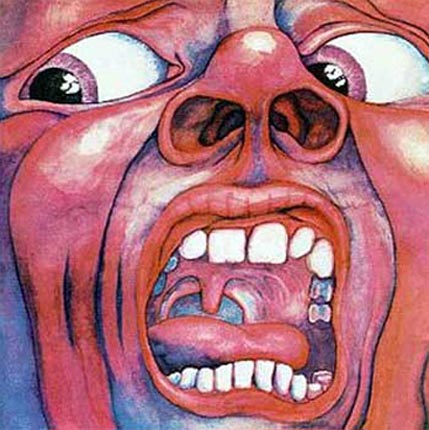

Another element of the template for prog set by the album was the cover, a brightly coloured nightmare face painted by Sinfield’s friend, Barry Godber. It seemed to have transcended packaging to become art in the same way the music appeared to have gone beyond simplistic forms to do the same. Prog acts that followed learned their lesson – Roger Dean’s images of alien landscapes arguably did as much for Yes’s popularity as any mystical lyric.

In the Court of the Crimson King opened floodgates. Yes, ELP, Pink Floyd and others sold prog albums by the tens of millions. Mike Oldfield’s 1973 Tubular Bells stayed in the UK chart for a year, while Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon has now sold nearly 50 million copies. But then came punk with its DIY minimalism and lo-fi ethic that almost instantly made any prog act look ridiculous. Robert Fripp wasn’t surprised – many of these prog acts had gone “tragically off-course”, he has said, adding, “KC had the wit to cease to exist in 1974; which makes those who associate KC, with ‘the bombastic excesses of prog rock’ and those who served them up, at least as dopey.”

Yet prog refuses to die. Annie Clark (St Vincent) has described how she learned to play Jethro Tull, one of the bands jolted into changing their sound by In the Court of the Crimson King, in her teens in a practice room decked with a King Crimson poster, while bands from Marillion through Radiohead to Mars Volta and Muse have used, abused, or reinvented prog (even if, like Radiohead, they vehemently refuse to admit it). And Fripp has reformed King Crimson several times in a variety of guises – this month the latest incarnation end a world tour.

Meanwhile, as McDonald says, “50 years later, the album still holds up”. He’s right, it does. Which is more than you can say for Tales of Topographic Oceans. With or without a curry.

To mark their 50th anniversary, King Crimson have put their catalogue on Apple music and Spotify. Ian McDonald’s current band, Honey West, have just released a “collector’s edition” of their critically acclaimed debut album, Bad Old World (www.honeywestmusic.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments