Kid A at 20: How the band’s self-alienating album saved an ‘unhinged’ Thom Yorke

As ‘Kid A’ turns 20 this year, and fans continue to enjoy the band’s new Public Library, Kieran Read explores how the album planted the seeds for the band’s new era of compassion and openness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tired? Irritable? Consumed with ennui?” asks a poster for the Radiohead Public Library. “Got the feeling everything’s f***ed?” As an apparent solution, it then invites you into an almost-comprehensive guide to everything the band has ever made, from albums to adverts, unboxing videos to unused artwork.

Suggesting that an immaculately organised Radiohead archive is the answer to all of your troubles is at once obscene and hilarious; describing their music as a “sunlit upland” is not unlike suggesting The Bell Jar makes for a great light read. Instead, these questions read like a knowing wink to the exaggerated public perception of the band themselves – miserable, lonely, and forever pessimistic.

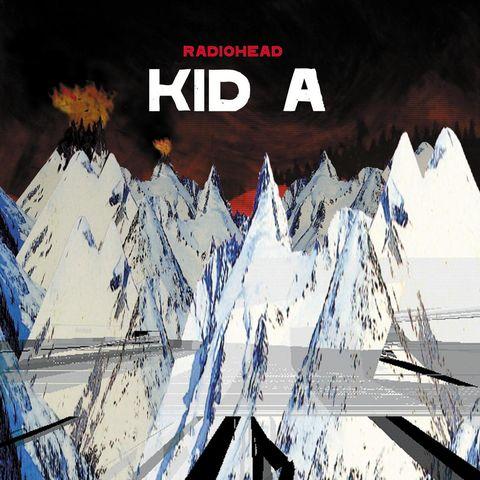

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Kid A, a snapshot of the group at their most introverted and polarising. A radical left-turn of an album that dips freely into IDM (intelligent dance music), psychedelia, krautrock and jazz, it rejected Radiohead’s unwelcome “rock and roll saviours” status and instead delved into previously unexplored electronic territory.

There has never been a better time to explore every nook and cranny of Radiohead’s artistic progression over the decades – something they seem to be actively encouraging with their Public Library. Diving headfirst into this wealth of B-sides, photocopied mail, live performances and restored merchandise reaffirms a lot of things. There’s an underlying altruism in their work that often gets overshadowed. And although their image as “depressed” doomsayers is undoubtedly exaggerated, dated and reductive, the root of this idea does come from a very real and troubling place.

Kid A couldn’t spell this out any clearer. You come to understand that, through the album’s experimentation, it was not just the skin of the famously self-loathed “Creep” the band were trying to shed, but also the instantly canonised and exhaustively toured OK Computer. Frontman Thom Yorke told The Guardian in 2000 that fame had left him “completely unhinged”, but once Radiohead finished recording Kid A, he started being “a bit easier on myself… because I understood a little bit better where I was supposed to be”.

Lyrically, the album would speak of spiralling, disappearing completely, sleeping pills and, with no shortage of irony, everything being in its “right place”. Radiohead would take not only musical notes from iconoclastic electronic pioneers Aphex Twin and Autechre, whose influence is found all over the convulsive “Idioteque” and glacial “Treefingers”, but similarly retreat from the public eye, offering no singles or interviews and rarely deigning to perform live. Instead, an embrace of the digital would fittingly characterise the album’s launch, including extensive online promotion and a relative nonchalance regarding the album’s leak on a prepubescent Napster.

By minimising human contact and turning to the great unknown of the online, which many considered anti-social and daunting during these early years, Kid A planted the seeds for a more accessible era of compassion and openness. This is something that would develop over the course of their career, such as with 2007’s In Rainbows, which was initially self-released as a pay-what-you-want download.

This model was truly uncharted territory for an act of Radiohead’s size. It would open the floodgates to both positive and negative criticism, throwing into question the monetary and artistic value of the form long before streaming. More importantly, and more personally, it would suggest the fans owe them nothing at all – promoting a mutual respect that belies a widely held perception that they are somewhat aloof with their audience.

Almost a decade later, the stunningly earnest A Moon Shaped Pool would take this giving philosophy even further. From resurrecting fabled fan classics (“Burn the Witch”, “Present Tense”, “True Love Waits”), to divulging intimate minutiae (“It was just a laugh”) and startlingly personal meditations (“Half of my love, half of my life”), Radiohead’s “sadness” had now evolved past Kid A’s alienation and instead offered something communal and cathartic. “We are just happy to serve you,” Yorke sings as plainly as he can on “Daydreaming”, relief found in the distributing of their works and the connections made through it.

From there on out, Radiohead’s acts of charity have become innumerable: their white whale and perennial fan favourite “Lift”, previously circulated as a bootleg recording, was officially released in 2017; more than 16 hours of OK Computer demos and rehearsals were uploaded after Yorke’s personal library was reportedly stolen and leaked online; segments of their master tapes dating back to the Nineties were distributed to the masses. Hell, they’d even start playing “Creep” without an ounce of sarcasm, on a tour Yorke would describe as therapeutic and enjoyable. All a far cry from Meeting People is Easy.

Which again leads us to the Public Library, a place where everything has been compiled in a way that is as accessible as possible for fans. It’s fascinating and perhaps not coincidental that the aforementioned Aphex Twin, an idol of Yorke’s when the frontman was at his most insular and angst-ridden, similarly catalogued his sprawling discography into a self-owned streaming platform a few years before. What sets apart the Public Library from Aphex Twin’s archive (and EMI’s ham-fisted attempt at box-setting Radiohead’s discography) is how heartwarming it is to see Yorke and co embrace a history they once seemed dead set on disowning.

The once-alien online platform adopted during the tumultuous era of Kid A has slowly come full circle, not unlike the band themselves, and ended up providing the perfect place to find “everything in its right place”. It proves there is strength to be found in unabashed honesty and acceptance of a complete legacy, warts and all. And in a career punctuated by unsung giving, the Public Library is perhaps Radiohead’s most bountiful and touching offering yet.

The greatest joy is that this career-long, complex tussle between Radiohead’s true self and their ever-stereotyped identity as a band is all there to be experienced. And it’s something they seem very happy for us to do.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments