Julian Lennon: ‘Today’s world is worse than I’ve ever lived through before’

The musician and activist just released his first album in over a decade, ‘Jude’. He speaks to Mark Beaumont about coming to terms with his own identity, fighting to save the planet, and the ‘shedding of a skin’ that took place when he changed his name

When hotel management called to tell Julian Lennon there was an indigenous tribe waiting for him downstairs, he didn’t believe it. “On the road, a lot of pranks are played,” he says, recalling a fateful day while on tour in Adelaide to support his ecological 1991 hit “Saltwater”. He had no idea that the course of his life and work was about to be fundamentally diverted. “I honestly thought it was a prank. ‘You have an indigenous tribe downstairs’, and I go ‘Yeah, right, send the coffee up’.”

Talked down to the lobby, Lennon found about 50 members of the Aboriginal Mirning tribe, one of the oldest in the world, standing in a semi-circle around a plinth. There, an elder presented him with a white feather and asked him: “You have a voice; can you help us?”

For Lennon, this was a bolt from beyond. “Listen,” he says, still convinced of the message he received more than 30 years ago. It was a pan-dimensional communique that would ultimately lead to him quitting music, in order to dedicate himself largely to philanthropic and environmental causes through his own White Feather Foundation. “Dad said to me – and I just thought this was very weird – that if something happens to him, the way that he was going to let me know that he was going to be all right, or that we were all going to be all right, was in the form of a white feather. So when she handed that to me, I got goosebumps. For me, that’s undeniable.”

Ahead of our interview, Lennon’s people politely ask that we don’t stray too far into the “dad stuff”. It’s the sort of request that always brings to mind the old Mitchell & Webb sketch, where a PR meets a journalist en route to the interview room, saying “now Neil will only talk about the new album. If you bring up anything he did in the Sixties he’ll terminate the interview.” To which the befuddled hack replies, “But he was the first man on the moon…” Lennon is, of course, his own artist with his own elegant ambient rock sound and his own colourful story to tell: exotic adventures, personal hardships, pop successes, cosmic revelations. But considering he’s here to talk about a new album – his first in 11 years – with the Beatle-adjacent title Jude, plus a cover single of his father’s “Imagine” in aid of Ukraine, it’s a tougher ask than usual.

In person, however, Lennon turns out to be quite open and philosophical about his background and the wild meandering journey it’s led him on. Settling into a sofa at his label BMG’s headquarters, smart-casual in tweed blazer and jeans and bleary-eyed from a 5am start (to appear on a Good Morning Britain set plastered with Beatles pictures) – his trademark earring the only hint of rock starriness about him – he exudes an everyman composure and tranquillity. The dichotomy of owing so much of his life’s experience and direction to a man – albeit probably the greatest musical genius of the 20th century – who left him and his mother Cynthia to largely fend for themselves when Julian was five, clearly bristles slightly behind his placid demeanour. But long gone is the sort of heat that saw Julian brand his peace-and-love icon of a father a “hypocrite” as his own music career took off with the John-indebted “Too Late For Goodbyes” in 1984. An artist in his own right, yes, but his voice and features reassuring signs of pop immortality.

“The whole shadow thing drove me nuts,” he admits. “‘You’re under the shadow…’ shut up, no I’m not. I never felt that way. It was only when other people brought that into the frame [that] it was a reminder of how people viewed me, because I would just get on with things.” Lennon’s fond and idyllic portrait of growing up with his mother and grandmother around the Wirral (“Mum and I [lived] very simply. Nobody knew who we were, really… we knuckled down and we got on and we survived”) is only jarred by the moments he’d arrive at a new school and be introduced by the headmaster to his new schoolmates.

“You had to stand up and it was ‘this is Julian Lennon, the son of John Lennon from The Beatles’,” he recalls in a stern headmaster voice. “And I’m going, ‘Really? You had to do that? Because you know how difficult it’s going to be to make friends now, with genuine people?’ Things like that, it was just soul-destroying because I just wanted to be me, get on with life. And we did for the most part, with little to no help from dad.”

Like his 2009 song “Lucy” – a tribute to his childhood friend and the inspiration behind “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds”, Lucy Vodden, naming his seventh album Jude was an act of reclamation that has left Lennon far more serene about his past than he was before. It’s a psychological “switch” that also involved legally changing his name to Julian in 2020 (he was born John Charles Julian Lennon). “That was a big deal,” he says. “Very much a shedding of a skin.”

He puts the transformation down to soul-searching his way through the pandemic, alone in his LA home. “I was on my own for pretty much two years,” he says, “and there really was a lot of looking in the mirror thinking, ‘Well, who am I? What’s my deal? What’s my purpose? Am I happy? If I’m not happy, then how do I change that?’ It was looking at pretty much every detail of my life and saying, ‘How do I achieve balance? How do I find peace?’”

There was a lot of looking in the mirror thinking, ‘Well, who am I? What’s my deal? What’s my purpose?

As a result, he feels he’s found forgiveness, closure. “It’s been in stages of getting to that point of finding peace along the way,” he says. “This is why Jude is Jude… it was to bring that attention so that I could tell whatever story I was going to tell from my perspective, my side, and it was very much taking ownership of that name and the journey that I’d been on. [And], for me, it marks a point in time that I think I’ve said all that I’ve had to say on the matters of dad and The Beatles. I don’t think there’s a question that has not been answered. For me, it’s the end of a chapter. I’m not going to let other people affect me in any way. I’m determined [to move] forward to remain in a positive headspace.”

And also make peace with the song? “Well, yeah,” he responds. “Most people think [“Hey Jude”, written by Paul McCartney for Julian] was just this chanty song and yes, OK, it was written as some kind of support for me. But I have to say I’ve probably heard it more than anybody else on the planet, so that was one thing.” What many people don’t consider, he says, is that the song was written during a “very dark and very difficult time” for him. “As a kid, I remember kicking and screaming a little bit going ‘where’s dad?’, but even early on I recognised that it was mum [who] I needed to be there for, to make her proud. I still feel that’s part and parcel of my purpose.”

If Jude sounds like a conscious, therapeutic move, it was actually something of a happy accident. After feeling used and commodified by the major label system during his Eighties and Nineties heyday, then growing tired of the intense effort involved with making and promoting his subsequent independent albums, Lennon dropped out of music altogether following 2011’s Everything Changes. “I just found that without significant support or sponsorship behind you, you’re kind of screwed,” he says. “I thought, ‘I’ve been doing this for 30 years; there are other things I want to do’.”

Never intending to make another album, Lennon took to fine-art photography, exhibiting in LA, Miami and New York. He wrote a trilogy of bestselling children’s education books, Touch the Earth, Love the Earth and Heal the Earth. He produced documentaries about the Mirning tribe (2008’s award-winning Whaledreamers), the native Americans of South Dakota (last year’s Women of the White Buffalo) and the desertification of America’s farmland in 2020’s Kiss the Ground. “Especially in America, they’ve basically killed the soil with every chemical known to mankind,” he says. “Not only are we screwing up every other aspect… I don’t think a lot of people realise how screwed up the land is.”

He also took to philanthropic adventuring, as part of his work with his White Feather Foundation. He visited Ethiopia to see the developments in clean water wells; Kenya to launch a scholarship in his mother’s name to put girls through college and instigate a mobile health clinic scheme; South America to meet with the ancient, once-hidden Kogi tribe, to help them buy back their ancestral coastal land. South America was a trip that involved sleeping out in the wilds of the Sierra Nevada in a three-walled shack with “things scampering across the roof” in the night and some rather invasive bug life. “I came back with a few extra friends,” Lennon confesses. “I flew back to Los Angeles and I was in the shower looking down at the crown jewels and noticed that I had some friends join the club. Thankfully not on, but in surrounding areas.”

The Kogi, Lennon discovered, came out of hiding after 400 years to warn the world. “There’s a specific mountain in the Sierra Nevada that’s quite pyramid-like,” he says, “and for as long as they can remember there’s always been snow. They’re seeing the snow disappear and they’re freaking out. That’s why they came down… they’re saying, ‘You’re killing us, you’re killing everything.’”

A stirring Jude track called “Lucky Ones” finds Lennon declaring “the world is burning while we’re dancing in our own pollution” but that “a change is coming… a new revolution’s knocking on my door.” “In today’s world there’s a lot more awareness of the state of affairs that we’re dealing with,” Lennon says of the song’s optimism. “Obviously, social media can be a good and bad place, but [for] those who wish to connect and work together for the betterment of all, it’s been a great communications leveller in many respects.”

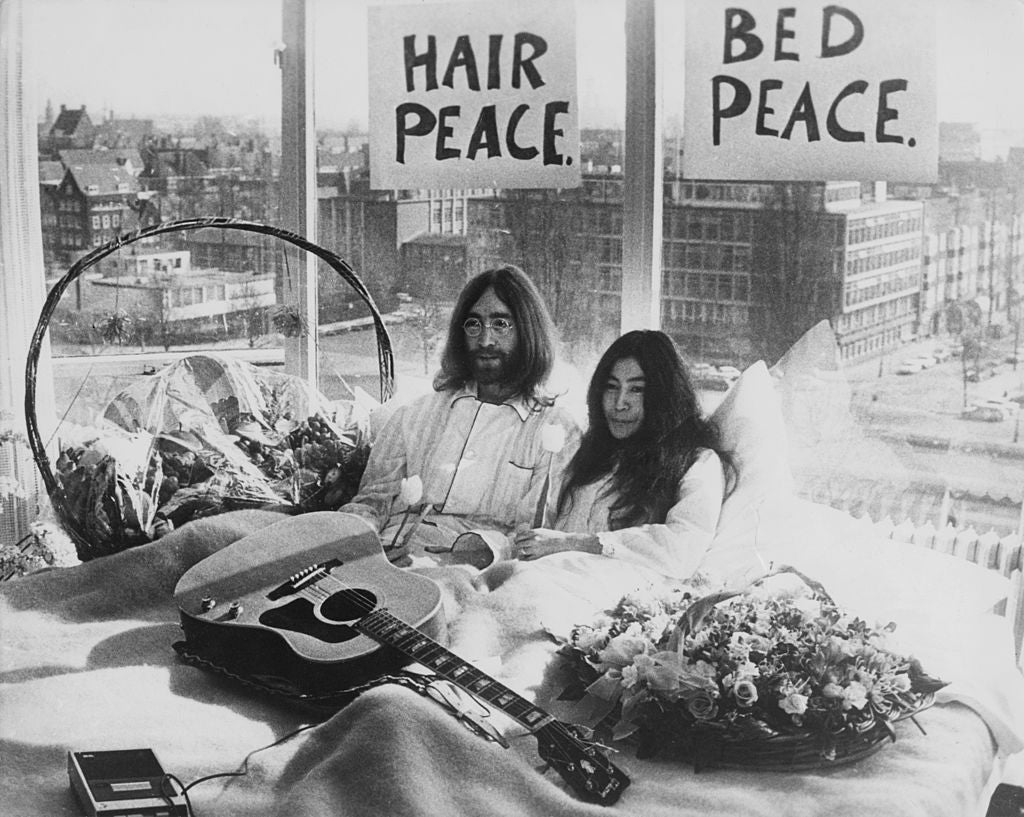

Considering the task of conveying the urgency of the climate crisis to politicians “impossible”, he favours education through filmmaking and direct action over symbolic protests such as John and Yoko’s Amsterdam bed-in. “You can make some waves with an artistic approach like that,” he says, a little dismissive but resolute. “But I think what counts more than anything is getting out there and trying to help it as much as possible. Actually making the change [by] buying back the land, by building schools.”

Meanwhile, a split with his management turned up lost boxes of over 100 tapes of demos and recordings from throughout his musical career, tracks that didn’t fit on previous albums but, when “baked” off of the original reels, “literally sounded like I’d recorded it last week”. Working remotely across the Atlantic with collaborators Ash Soan and childhood friend Justin Clayton during lockdown, Lennon stripped off the Eighties drum machines, brushed up the vocals and production and – after much cajoling from friends and label believers – caught the “buzz” for writing new songs again.

“I really had no interest in doing another album,” he stresses. “I thought maybe a single or EPs would be the way to go because there’s a lot less pressure with that. I just thought if I release any music I know I’m not going to stop, especially now I have a box of a couple of hundred tapes. I’m rebuilding a little home studio now, so I’m screwed.”

What emerged was a rounded, contemporary album, both sonically and personally cathartic. Not only does it update Lennon’s rich orchestral and electronic pop tones, but its songs are sonic diary entries from the past that have helped Lennon process the more difficult steps along his 40-year musical journey – his lack of confidence and belief, the moments of self-deprecation and despair. Tracks such as “Save Me” and “Round and Round Again”, in which Lennon confesses to having “lost control” and “had enough”, he explains, are chapters about growing up. “Stay” is a clutching hand at those friends on the brink of suicide.

“I’ve certainly dealt with panic attacks, anxiety and depression quite heavily in the past,” Lennon says. “Not so much anymore, thankfully. But [“Stay”] was about friends like that, people who pretty much want to take their own lives, that are numb to the world and the love around them. It’s saying, ‘Don’t leave, I’m here for you.’”

“Every Little Moment”, meanwhile, is the album’s strident and somewhat funky peace statement, written 30 years ago with a genetic Lennon idealism: “Let go of your rifle, let go of your mind/And think with the vision of peace in our time.” Does he find it hard to summon the same optimism today?

“It’s very, very difficult,” he says, nodding. “It’s horrible out there. It’s worse than I’ve ever lived through before, with the veiled threats from Russia, and North Korea flying tests over Japanese airspace. Really? Why do you want this in your life? What is this kind of power? I don’t understand why people do not want peace. But I’ve got to keep hopeful – that’s the only way I stay positive.”

Lennon is undoubtedly more of a “Getting Better” than a “Saltwater” kind of guy these days. His relationship with half-brother Sean goes from strength to strength: they video call each other “at least a couple of times a month” and recently took a road trip together over the Santa Monica mountains in a Mini convertible. “We’re more than brothers, we’re such good friends,” he says. “I wish we had more time together.” He speaks fondly about the bond of support he enjoyed with his mother, who died in 2015, and how recording an acoustic “Imagine” with Extreme’s Nuno Bettencourt for the Stand Up for Ukraine project has helped him come to terms with his musical heritage too. From his earliest songs, the open and honest simplicity of his father’s solo work found its way naturally into his own.

Sean and I are more than brothers, we’re such good friends

“I’ve never had a persona or facade in life or in any of the work,” he says. “What you see is what you get. I did love songs like ‘Isolation’, that was one of my all-time favourites… I just loved that raw, straight in there.” He’d assumed he would end up covering “Imagine” at some point, but never felt compelled to sing any of his dad’s songs. “Why?” he shrugs. “I understand that people are a bit crazy and are still waiting for all the Beatles children to come together, but that’s never going to freakin’ happen. But since having done that song, the response... I’ve garnered more respect in my life, musically, as a person, as an artist in music than ever before.”

A sense of purpose fills his voice. “All I can say is that this whole journey over the last year or so has been a cleaning out of the cobwebs. After having proven myself to myself first and foremost with all the other stuff, I just feel like getting on with things now.” He’d always felt as though he was being held back in the past. And now? “I don’t care. I just want to do a good job, move forward, be positive, try and help where I can and live a happy life, if possible in today’s world.”

That’s Jude, the world shaken from his shoulders, taking sad songs and making them better.

‘Jude’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks