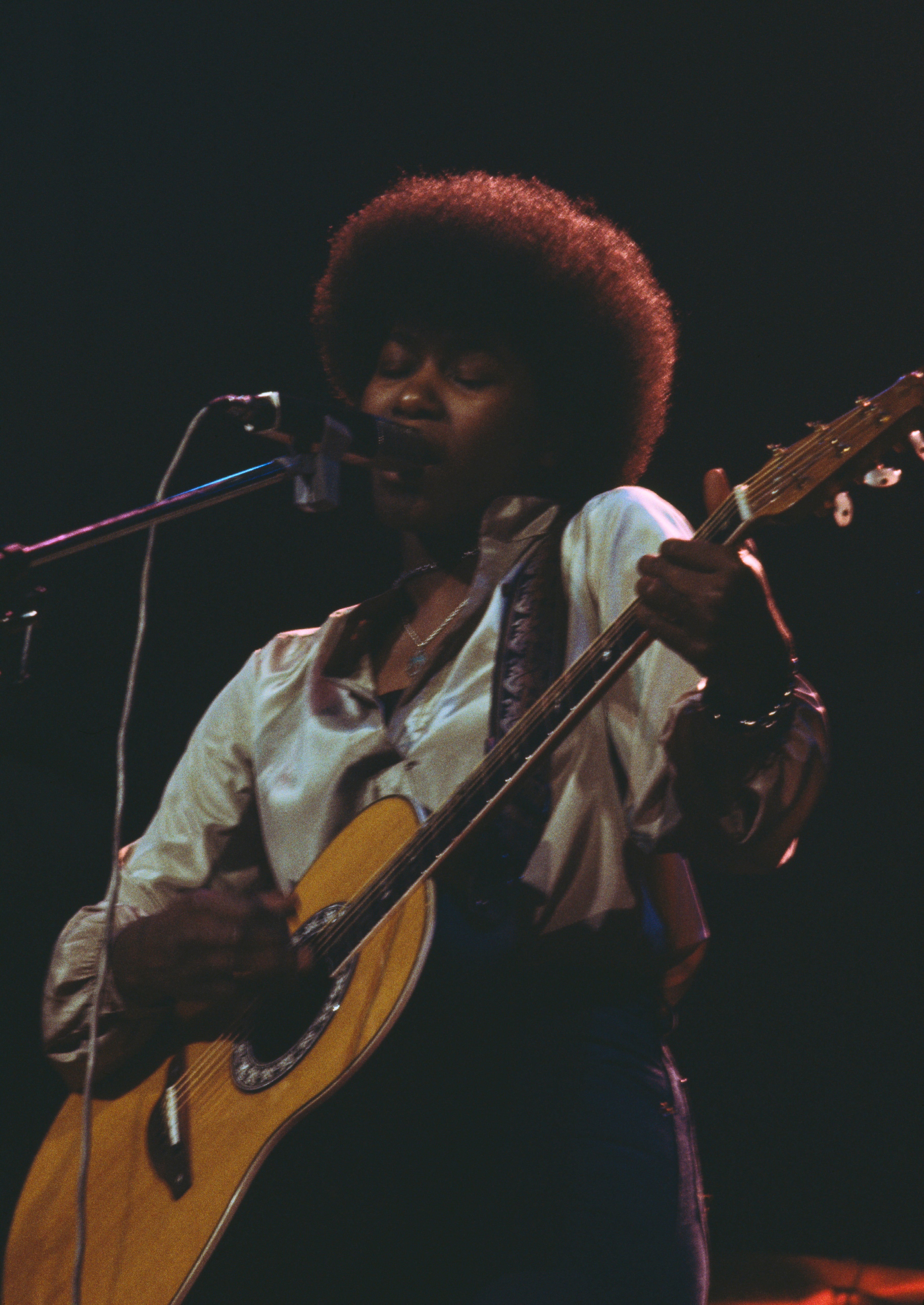

Joan Armatrading: ‘I love a good gossip – but there’s a reason I won’t discuss my private life’

The pioneering singer-songwriter behind ‘Love and Affection’ and ‘Willow’ speaks to Louis Chilton about her coruscating new album, witnessing a frantic public ‘meltdown’ and channelling the story into music, and her steadfast refusal to live life in the public eye

I write about people,” says Joan Armatrading, “whether they’re in love, out of love, looking for love, in love with a place – in love with whatever.” Over the past half-century, the 73-year-old singer-songwriter has been one of music’s foremost chroniclers of love, in all its myriad forms and complexities. And she’s damn good at it. It is love that courses so potently through ballads such as “Willow”, “All the Way from America”, and, of course, “Love and Affection”, Armatrading’s biggest hit, now nearly 50 years old.

The music scene has changed a lot from those early days, when Armatrading blazed a trail for Black British singer-songwriters – and female singer-songwriters in general – but it’s still the same love that pours from her musically dextrous new album, her 21st, How Did This Happen and What Does It Now Mean. “I’ve been doing this for a long time,” she says, “and I still get the same thrill, writing the song from beginning to end. It’s quite a thing, you know?”

Armatrading’s voice – warm, firm, and contoured by the recognisable inflections of Birmingham (where she grew up, having moved from the Caribbean at six years old) – comes from my laptop over an audio-only Zoom call. The CBE-honoured musician conducts most of her interviews this way; it’s a fittingly opaque set-up for an artist who has steadfastly kept her celebrity at arm’s length. Since the very start of her career, Armatrading has refused to discuss details about her personal life, save for what she describes as a few oft-repeated “snippets” – her father’s refusal to let her play guitar as a child, or the time her mother pawned two prams in order to buy her the instrument. “But these [stories], to me, are part of my career,” she says.

Small biographical formalities have unavoidably made their way into the public domain. We know, for instance, that Armatrading lives a relatively quiet life in Surrey, with a music studio built into her home. We know that in 2011, she entered into a civil partnership with the artist Maggie Butler. On this, though, and everything else current or personal, she is, as ever, keeping schtum. What she will talk about, jovially and unabashedly, is the music.

“I’m Not Moving”, a defiant and fiercely catchy pop-rock number that serves as the new album’s first single, was written after Armatrading witnessed “a young person having a meltdown” in public. “They were so determined that nobody was going to move them from where they were,” she recalls. “Literally saying, ‘I’m gonna kill everybody’, getting quite heated. I’m watching this thing, and as I’m watching it, I’m writing it.”

Armatrading has used a similar approach in the past. Take 1995’s “Everyday Boy”, one of several Armatrading songs embraced and championed by the LGBT+ community, which was written after a conversation with a man whose boyfriend’s mother thought her son’s same-sex relationship would kill him. “The Shouting Stage” (1988) was penned after she overheard a couple having a public row at a restaurant in Australia. “The thing I’m pretty sure I know is that, in all of those instances... I’m the only one that went and wrote a song about it.”

There’s a “responsibility” with observational songs such as this, she adds, “to tell it so that people can understand what you’re saying, and not just make it a pop song, if you like, because it’s real. You don’t want to necessarily name names, but you do want it to be real, and sympathetic to the situation, if you can be.”

“Someone Else”, another standout track from How Did This Happen, feels, in the best way, like a song ripped straight from the early 1980s. Armatrading’s sound has evolved over the years, but there’s something delightfully retro about much of her new record. The album also features two instrumental tracks, involving lengthy, intricate guitar solos from the artist herself. In fact, Armatrading plays all the instruments on the record, and even produced it – something that has been the case now for decades. “It’s not because I’m trying to show off or be clever or whatever,” she laughs. “It’s nothing to do with that. I’ll pick up stuff just to see if I can do it... but you wouldn’t want me playing drums in your band.” She laughs a lot over the course of our conversation; if her reputation for personal discretion had led me to expect someone prickly and taciturn, I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Armatrading has remained prolific down the years, despite so much of the musical workload falling upon her shoulders. “I’m on my own, and I’m very quick,” she says, offhandedly. “Even if I’m in the studio with musicians, it’s a quick process for me to make a record.” Part of the reason for this is Armatrading’s adroit understanding of technology – unusual, perhaps, for an artist of her generation.

“When a new thing comes in, I’m immediately on it,” she says. “I started off with my little cassette thing, then my two-track, my eight-track... I built up all the time. When computers came in, I got the computer. I try and stay with the technology of the day, only because I’m interested in it. When we had the pandemic, I was able to make my album [2021’s Consequences] with no kind of disruption. It wasn’t a big shock or surprise for me.”

But then, Armatrading has always been one to plot her own course. Before the release of her first album, 1972’s Whatever’s for Us, record executives suggested that she “change her name, dress a certain way, [and] do cover songs. None of those things happened,” she adds. When did they get the message? “Day one. I said ‘No’, and no means no,” she says.

Whatever’s for Us, which employed a folkier sound than much of Armatrading’s later work, has stood the test of time remarkably well, but failed to make a splash commercially. Her follow-up, 1975’s Back to the Night, was a huge step forward, and featured some of her most enduring songs – most notably the potent, pared-back love ballad “Dry Land”. “It did all right, but it wasn’t the breakout album, as it were,” she says. “A&M [her record label at the time] were absolutely fantastic. They recognised that an artist needed time to develop, and they didn’t say, ‘Well, Joan, that didn’t work, you need to leave.’”

Whether you’re talking about me or Beethoven, we’re starting everything from scratch

Their faith was immediately repaid, with her self-titled third album. Joan Armatrading (1976) included songs such as “Love and Affection” and “Down to Zero” – big, sweeping ballads that showed off her powerhouse contralto and became staples of her live act for decades. “That’s where it all kicked off,” Armatrading says. “But [A&M] recognised that in me, and all their artists. They gave me space and allowed me to do whatever: that was the beauty of that. If somebody would suggest I change something, it wasn’t often repeated – I’m pretty settled in me. I kind of know myself.”

Over the decades, Armatrading would continue to innovate, to stubbornly pull against easy categorisation. She’s recorded jazz music, pop music, reggae music, and in 2022 composed her first symphony. Is that not daunting, I ask? “Not to me! Nobody asked me to do it,” she says. “I just wanted to.” The composition, performed by the Chineke! Orchestra at London’s Southbank Centre last November, wasn’t the end of her classical ambitions; she’s now written a choral piece for the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra’s 100-piece choir, which will be performed next year.

“If you think of all creatives, all we’re doing is making stuff hard,” she continues. “Whether you’re talking about me or Beethoven, we’re starting everything from scratch.” She never gets writer’s block – “I’m very lucky, I don’t struggle that way” – something she attributes, in part, to an intractable songwriting rule of hers. “If I start writing something, good or bad, or whatever, I’ll always finish it,” she says. “I think if I start a song and I stop halfway through, I might stop halfway through the next time.”

Armatrading is still as creatively energised as ever, but her days as a live act are seemingly behind her. Since her 2018 solo tour of the UK, she has performed live only twice, most recently playing a five-song set at a Teenage Cancer Trust benefit at the Royal Albert Hall last year. When I ask her if she misses touring, she replies, flatly: “No. No.” She breaks into laughter. “No, no, no.

“I think you have to go with where your head and your heart are,” she says. “And my head is completely in writing at the moment.” She mentions again the guitar-fronted instrumental tracks on How Did This Happen. “What was so nice about doing those was not having to think about playing it on stage. It’s so freeing.”

Despite her willingness to discuss her music, Armatrading has been, as promised, resolutely coy about her personal life. I can’t help but wonder whether she’s ever had second thoughts about this barrier, whether she ever imagined what her life would be like if she had opted to welcome her fame from the off. “No,” she replies. “I knew straight away that I didn’t want to be talking about myself – I’m not gonna get into family dynamics and stuff like that.

“I love a gossip,” she adds. “I read gossip magazines till the cows come home. Absolutely love it – but I don’t want to be in one. That’s not for me. It’s important that there’s things that only I know.”

With just a whiff of mischief, she turns the tables. “Let me ask you a question,” she says. “I bet you’ve got a lot of friends. Do you tell all your friends exactly the same bit of information about you?” No, I reply, obviously not. “Thank you. That’s how it goes,” she says, confidently.

“There’s certain friends that know all the intimacy you want to know, down to the nth degree. And then there’s other people who only really know what you’re going to have for lunch. So why, as somebody who’s an artist, should you tell the world all about you? Because it’s not just your village, or your city, or your country. You’re literally telling the world everything about yourself. That makes no sense to me!”

Have interviewers finally taken the hint at this point – have they stopped asking the questions? “No,” she replies, before breaking into one last characterful laugh.

“But I don’t have to answer.”

‘How Did This Happen and What Does It Now Mean’ is out on 22 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks