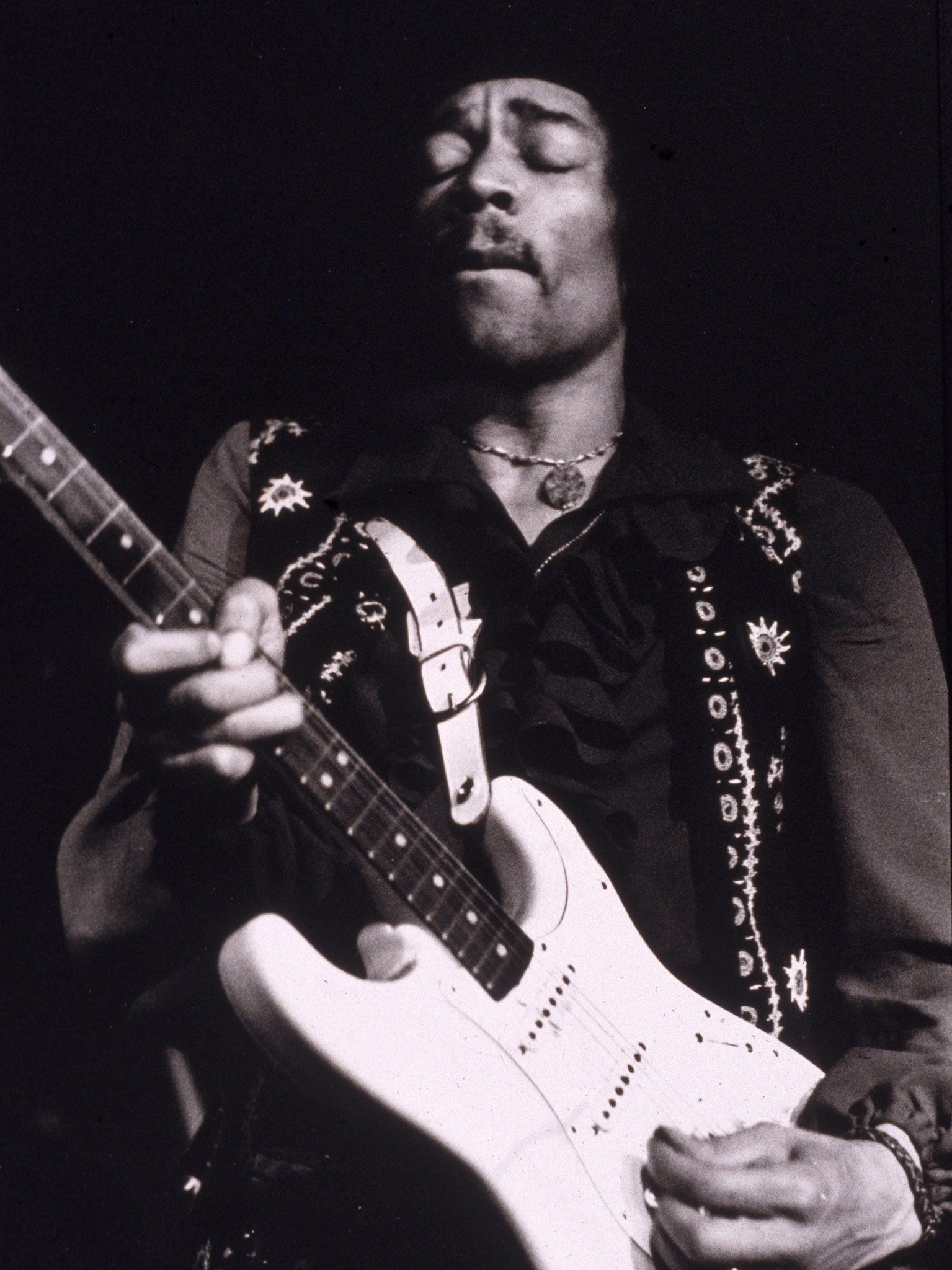

Jimi Hendrix biopic: How do you make a movie without the music rights?

You want to make a movie about a rock superstar, but you can’t use any of their songs. It’s not a new problem, and directors have faced it in different ways

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The rock biopic has become a Hollywood staple, enabling film studios to cash in on the legacy of some of music’s biggest icons, like James Brown, Johnny Cash or Jimi Hendrix. Producers see them as win-win propositions sure to attract the people who grew up with those larger-than-life stars as the soundtracks to their lives, as well as younger cinema-goers who have discovered them more recently now that all music is available on the internet. Yet, there is a world of difference between Get On Up, the new Brown biopic starring Chadwick Boseman, or Walk the Line, the 2005 film featuring Joaquin Phoenix as Cash, and All Is By My Side, the Hendrix movie with André Benjamin, aka André 3000, of Outkast fame.

What is amazing is that, unlike Get On Up or Walk The Line, the biopic was made without securing the rights to any music written by the legendary guitarist. All Is By My Side didn’t get the green light to use “Purple Haze”, “The Wind Cries Mary” or “Voodoo Chile”, the major hits composed by the guitarist.

Instead music supervisor Danny Bramson cleverly circumvented the limitations by using period songs by acts like Bob Dylan, Buddy Guy and The Seeds, and material Hendrix covered, including “Wild Thing”, the Chip Taylor composition made famous by the Troggs, and “Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”, the title track from the 1967 Beatles album which the guitarist performed at the Saville Theatre in London’s West End three days after its release.

Bramson also tasked versatile US sessioneer Waddy Wachtel, who has played with everyone from Stevie Nicks to Keith Richards via Linda Ronstadt, to create original instrumental material matching Hendrix’s shifts in sound and style from Café Wha? in New York’s Greenwich Village to the emergence of the Experience in London in 1966.

All Is By My Side is only the latest in a long line of music biopics that are patently based on or about specific artists but don’t include original material by them. The list reads like a Who’s Who of popular music, starting with Elvis Presley, surely the inspiration for Jeep Jackson, the conscripted star portrayed by Anthony Newley in Idol on Parade, the delightful 1959 comedy curio directed by John Gilling, later a master of British horror, and for Eli Caulfield, the star of Living Legend: The King of Rock’n’Roll, played in 1980 by B-movie specialist Earl Owensby, who cast Presley’s last girlfriend, Ginger Alden, and lip-synched to a soundtrack recorded by Roy Orbison!

The Fab Four have kept a tight hold on their legacy via their company Apple Corps but in 1979 they couldn’t prevent Dick Clark Productions from making Birth of the Beatles, a biopic directed by Brit Richard Marquand that majored on their early repertoire of rock’n’roll covers and, thanks to a legal loophole, since closed, included half a dozen of their early self-penned hits re-recorded by tribute band Rain, as well as input from original Beatles drummer Pete Best. Backbeat, Iain Softley’s 1994 evocative drama about “fifth Beatle” Stuart Sutcliffe and their time in Hamburg, also relied on covers for its edgy soundtrack cut by a grunge supergroup including Dave Grohl of Nirvana on drums.

Other Beatles-related films have concentrated on specific events, like The Hours and Times, Christopher Münch’s fictionalised account of a holiday John Lennon and Fab Four manager Brian Epstein took in Barcelona in 1963, and Two of Us, Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s speculative tale of the last meeting between John Lennon and Paul McCartney in 1976, while Nowhere Boy, Sam Taylor-Wood’s engaging 2009 film about Lennon’s teenage years, scored a rare coup by securing permission from Yoko One to use the Lennon composition “Mother”.

Stoned, 2005’s Stephen Woolley’s attempt to film the tragic story of Rolling Stones founder Brian Jones and untangle the mysterious circumstances surrounding his 1969 death by drowning, had to make do with a soundtrack featuring the Counterfeit Stones and A Band of Bees doing carbon copies of “Little Red Rooster”, “Not Fade Away” and “Time Is On My Side”, the blues, rock’n’roll and soul material the Stones performed in their early days, when the haunting “Sympathy For the Devil” would have been a better match for its dark mood.

The Rose, the 1979 movie that launched Bette Midler’s big screen career, started life as Pearl, named after the last Janis Joplin album, but underwent a swift rewrite when her family refused permission to use her music, though the picture still included a tour-de-force rendition of “Stay With Me (Baby)”, the Lorraine Ellison soul standard Joplin also performed. Beyond the Doors, a beyond-the-pale 1983 B-movie, supposedly exposed a CIA plot to assassinate Joplin, Hendrix and Doors frontman Jim Morrison, but didn’t even get the near negotiating table to acquire music rights and relied on soundalikes (and a would-be Woodstock-like performance filmed, ahem, indoors!).

Last Days, Gus Van Sant’s 2005 re-imagining of the final days of a troubled singer named Blake, a character clearly based on Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, kept well away from the music of the grunge trio with a soundtrack partly recorded by its lead actor Michael Pitt, yet proved surprisingly effective at conveying a possible version of the events leading up to his suicide.

Van Sant had probably paid close attention to the career of fellow maverick director Todd Haynes, who has enjoyed contrasting fortunes with the three music biopics he has made.

Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, the unusual 1987 short Haynes directed at university, fell foul not only of Mattel Inc for its use of Barbie dolls butchered to portray the singer’s struggle with anorexia, but also offended her brother Richard. He sued for copyright infringement and won hands-down since the director had made no attempt to licence any of the Carpenters’ music in the first place. The Museum of Modern Art in New York now owns one of the few copies that haven’t been destroyed but is not allowed to screen the short.

Haynes learnt his lesson and approached Bowie when planning 1998’s Velvet Goldmine, a big-budget film co-produced by REM’s Michael Stipe and Harvey Weinstein. It should have been Ziggy Stardust meets Lou Reed and Iggy Pop in the glam era of the early Seventies writ large, with Rhys Meyers as Brian – I kid you not – Slade and Ewan McGregor as the composite Curt Wild, and references to the bisexuality Bowie flirted with to attract notoriety. Yet Bowie didn’t allow his compositions to be used, forcing Haynes to switch to the Roxy Music, Brian Eno and Cockney Rebel catalogue, performed by Venus in Furs, comprising Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood from Radiohead and former Suede guitarist Bernard Butler, with underwhelming results.

It would be third time lucky for Haynes, who finally got his way with I’m Not There, his 2007 movie depicting various facets of Bob Dylan, portrayed by six different actors including Cate Blanchett, Christian Bale and Richard Gere, and a soundtrack combining Dylan’s music and covers by Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder, Stephen Malkmus and assorted members of Sonic Youth, Television and Wilco named The Million Bashers. Proving that, in the convoluted world of rock biopics, you shouldn’t panic if you can’t clear the soundtrack, but it all comes to he who waits.

‘All Is By My Side’ is released on 10 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments