Jackson Browne interview: Co-writer of the huge Eagles hit on new album and political activism

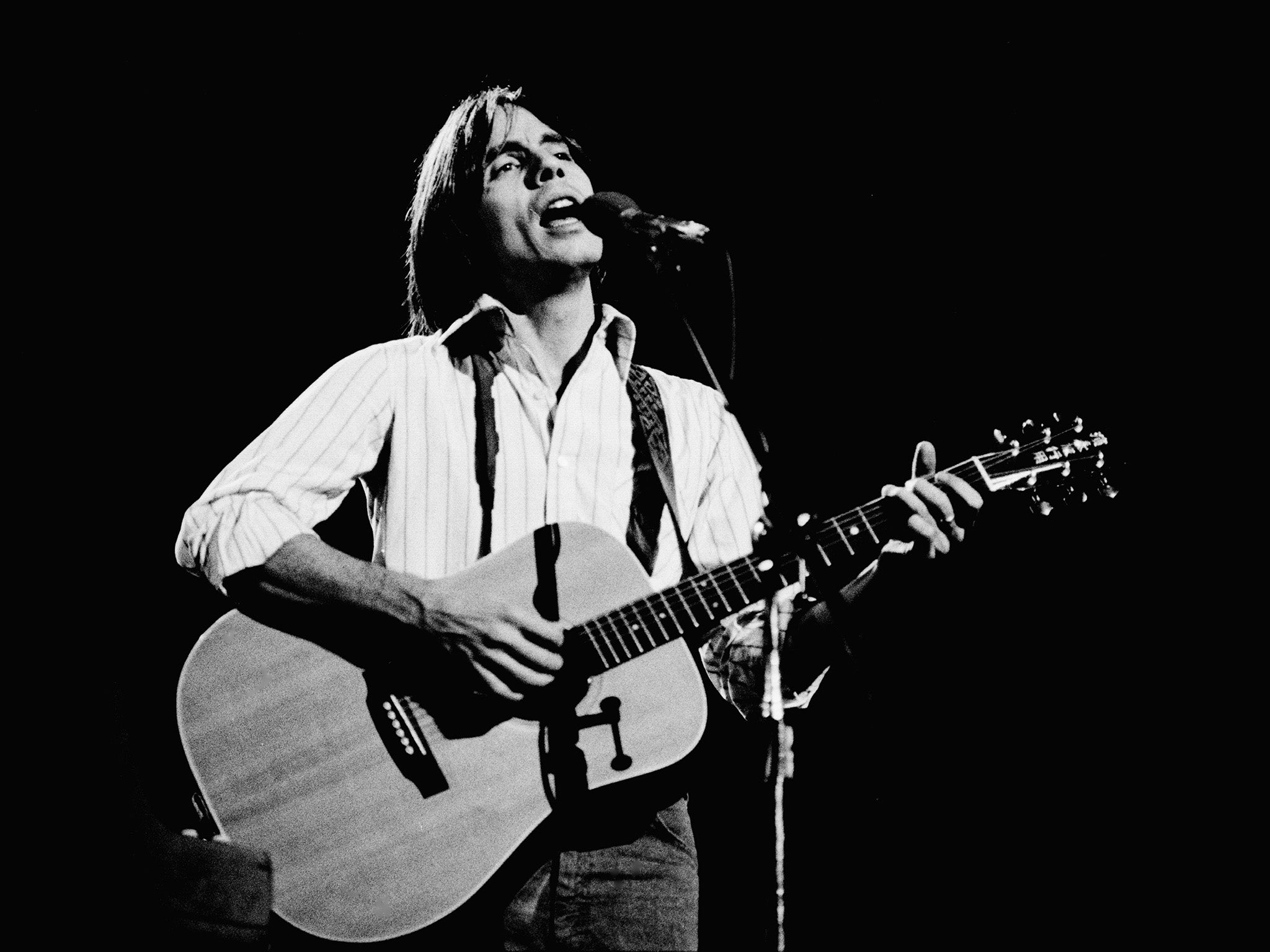

Browne, who still looks every inch a rock star with his luxuriant hair and open-necked shirt, is frustrated with big business

“Eternity is a really, really long time, especially towards the end,” quips Jackson Browne, quoting Woody Allen.

The trim 66-year-old, who wrote some of the most enduring folk-rock tracks of the 20th century, is still politically engaged and concerned with many “big” issues – climate change, the nuclear industry and America’s gun laws – but he also has a healthy sense of humour (he does an adroit Ronald Reagan impression) when we meet in the bedroom of a plush hotel overlooking Kensington Gardens.

Browne’s latest album, Standing in the Breach, is his 14th in a solo career that began with 1972’s Jackson Browne, followed the next year by the timeless For Everyman, which features the exquisite lament “These Days”. A song full of loss and remorse, written when Browne was only 16, which was covered by Nico and of which the sexagenarian admits, “there aren’t many songs as good as ‘These Days’ that I wrote in those days.”

His new material, his first in six years, stands up supremely well and the sumptuous “The Long Way Around” (which begins with “I don’t know what to say about these days”) could seamlessly nestle on any of his Seventies gems, such as For Everyman, Late for the Sky and Running on Empty. The song blends Browne’s trademark introspection with a stark, slightly jarring statement about guns: “It’s never been that hard to buy a gun/ Now they’ll sell a Glock 19 to just about anyone.”

“I admit that the gun reference arrives quite suddenly,” maintains Browne. “But it was a very brief opportunity to say something about it.”

Of all America’s current issues, the gun one appears to exercise Browne the most. He emphasises that the National Rifle Association is “too strong”, that Barack Obama “hasn’t taken much of a stance” and that the weapons manufacturers “saturate the media with their messages”.

“There have been about 37 gun massacres since Sandy Hook where 20 children were murdered, they happen all the time, it’s not even news any more,” Browne maintains. “Now you have people turning up in supermarkets with fully loaded assault weapons because they have the legal right to do it.”

Browne doesn’t hector. He’s very considered and droll with flashes of despondency (“we can’t continue in this downward spiral”), a bit like one of his songs. New song, “Leaving Winslow”, for instance, is whimsical (“my mother married an oxygenarian ladies man”), political (“I keep on hearing ’bout the disappearing ozone layer”) and, ultimately, poignant, finishing on the line “I figure I’ll be doing some disappearing myself”.

Browne, who lives at his California ranch “off-grid”, with his self-made wind-generator, doesn’t have the high profile he generated in the early 1980s, around the time of “Somebody’s Baby” and his relationship with Splash star Daryl Hannah, but he remains hugely admired by his US contemporaries. His close friend Bruce Springsteen inducted him into the Hall of Fame in 2004 with the spicy line, “Jackson was a bona fide rock’n’roll sex star”, and a tribute album to Browne, Looking into You, featuring Springsteen, the Eagles’ Don Henley, and Bonnie Raitt, was released early this year.

“In my country, and it’s not necessarily true here [in the UK], musicians are accorded a certain amount of time and you can keep on doing it,” he maintains – and he is impassioned on the subject of a musician honing their craft.

“It takes a lot of time to get to be a musician, you have to spend a lot of time practising what looks like nothing to other people, to make it look like you’re not doing anything,” he emphasises. “You need isolation and you need a certain amount of room, you need a buffer zone, sometimes you just need a girlfriend. What do you call a musician without a girlfriend? Homeless.”

Browne, who has been married twice, to model Phyllis Major (who committed suicide in 1976) and Australian model Lynne Sweeney (whom he divorced in 1982), has been with environmental activist Dianna Cohen since the 1990s and climate issues are very close to his heart. He bristles at any suggestion that today’s youngsters are less activist than they were.

“Four hundred thousand people just walked through the streets of New York about climate change, and I marched along with a lot of young people,” he argues. “Alternative energy is extremely do-able, it’s the more holistic and sustainable thing to do, he adds. “Nuclear power can’t even survive in the market place without government subsidies.”

He’s frustrated with big business, such as agrochemical firm Monsanto, the recent nuclear renaissance (“none of which addresses the waste problem”), and even the concept of democracy (“there’s the possibility that democracy doesn’t work, that it’s not viable”), citing Socrates who was “not in favour of democracy”.

Browne is extremely adept at steering the conversation and seems more at ease talking about campaigning topics than his own music, but he bristles again (quite rightly) with any suggestion that he’s less creative now than he was in the Seventies. “I’ve had people say all along, ‘I saw him when he was 18 and he was better then’, and they said it when I was 22 and 28 and 35, people prefer what they’ve already heard,” he claims. “If you listened to them you wouldn’t really make any of the music you made after you were 18.”

Browne, to some extent, has always had to combat the naysayers. Right from the start Atlantic Records’ Ahmet Ertegun infamously challenged his business partner David Geffen with: “If he [Browne] is such a big star, why don’t you do it yourself?”

So music mogul Geffen did and set up Asylum Records to sign him. Browne has always been unjustly knocked for being too laid-back, taking a bit too easy (his hit “Take It Easy” – a hit for the Eagles – is quite possibly most insanely addictive earworm ever written).

Browne, who still looks every inch a rock star with his luxuriant hair and open-necked shirt, is a survivor though, just like his hero Bob Dylan, whom he first saw play aged 15 in Santa Monica.

“Bob was on 60 Minutes a few years ago and he said that there was a time in his life when he was ‘doing magic’, like something was passing through him and he said ‘I could do it then but I can’t do it now,” he asserts. “It’s a courageous, brilliant and generous of him to say that and why should you have to do it again. It doesn’t have to be done twice for me. But he could be speaking for everyone when he says, ‘you can do it once, you don’t have to do it again’.”

Browne himself has come back time and again and his latest record is a testament to the durability of this exceptional American talent.

Jackson Browne performs at London’s Royal Albert Hall on 24 November. His latest album, ‘Standing in the Breach’, is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks