‘They booed Joni Mitchell and threw s**t at Jimi Hendrix’: The amazing story of the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival

Kris Kristofferson hated it, the compere had a meltdown and called the audience pigs, but 50 years ago, the counterculture brilliance of the Isle of Wight weekend set the tone for UK festival culture. Mark Beaumont tells the story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For the counterculture rebels of the mainland, it was a pilgrimage. Across the Solent on ferries filled with dope smoke and acoustic guitars, to join the revolution at Britain’s very own Woodstock. For the residents, it was an invasion – 600,000 hippies filling the hillside at Afton Down to dance ’til dawn to drugged-up, destructive and sexually deviant rock’n’roll degenerates like The Who, The Doors and Jimi Hendrix.

And for the wider culture, the Isle of Wight Festival of 1970 – by far the biggest festival ever held in the UK at the time – was a watershed. When it opened its gates 50 years ago next Wednesday, the scale and success of the event (in all but financial terms) made it not only the essence of Sixties liberation, but also its culmination. The Woodstock festival had crystallised the Sixties dream in August 1969, but the violence of Altamont – the free concert at which an audience member was stabbed to death during a set by The Rolling Stones – had shattered it just four months later. Now glam was about to plant its sequinned stack heel atop the charts. As such a huge, all-but-unrepeatable event teetering on the turn of the decade, Isle of Wight 1970 represented one last blow-out for the flower power generation. Many saw the flare billowing from the roof of the IOW stage in the wake of Hendrix’s set as symbolic of the Sixties going up in smoke.

Yet IOW 70 was as much a beginning as an end. It set the blueprint for major camping festivals like Glastonbury, and embedded the hedonistic, hippie-vibed weekend at the heart of the British summer to this day. And it was a small miracle it happened at all. Organisers Ray, Bill and Ron Foulk had launched the festival in 1968 with a far smaller 10,000 capacity one-day event headlined by Jefferson Airplane. So the reassured locals had the shock of their lives the following year, when 150,000 people descended on the island to watch Bob Dylan play his first show in three years.

“We realised that to get people to go to the Isle of Wight for a festival, you’ve got to put somebody on that’s pretty special,” says Ray Foulk, author of two volumes of When the World Came to the Isle of Wight, telling the story of the festival’s genesis. “The Beatles weren’t working, you had Elvis Presley, who at the time was past his best, and then you had Bob Dylan. We didn’t really know any other names that would really draw people across the water to the Isle of Wight. So we went for Bob Dylan and we were very fortunate that we managed to book him, it was an amazing coup. The whole world was beating a path to the Isle of Wight and it was massive. That was the start of the big festivals.”

For the 1970 event, there was no such crowd-drawing icon available, so instead Ray and his brothers put together a bill crammed with the biggest names they could book: among them The Who, Joan Baez, The Doors, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Miles Davis, The Moody Blues, Jethro Tull and one Jimi Hendrix. “Hendrix was not seen as being a giant name at that time,” Ray says. “These days young people would think Hendrix was bigger than Bob Dylan, but we thought Joan Baez was probably the biggest name. We didn’t treat Hendrix in the way we’d treated Dylan, as though he was a great superstar. We didn’t even bother to arrange his transport for him. But Hendrix increased in stature between booking him and the actual event… the Woodstock film made Hendrix into a big star.”

The film, released in March 1970, had also stoked Europe’s appetite for its own lawless hippie utopia and further terrified the Isle of Wight residents who had had a year to mobilise against another major festival on the island, and all the nudity, drugs, vandalism, disease and degradation it would doubtless bring to their doorsteps. The island’s Conservative MP Mark Woodnutt spent three months trying to get parliament to ban the event.

“We had to fight like fury for the whole of that year to keep the show on the road,” Ray says. “We had great difficulty getting a site because wherever we went opponents were using dirty tricks to threaten farmers and various other things.” He quotes one prime local objector, the wonderfully named Admiral Sir Manley Power: “He said that festivals were down to black power and communism. That was their state of mind. They thought that the whole drug thing was a threat, that sexual promiscuity was a threat and the political thing of young radicals were a hippie cult.”

When the Foulks finally managed to secure a site adjacent to Afton Down from farmer David Clarke for a reported £8,000, they faced an assault on a different front. While they struggled to put up fences to keep people off the hill, where they would get a grandstand view of the stage without having to pay the £3 entrance fee, French communist groups who felt that all music should be free (and had successfully thwarted two French festivals that year) would tear them down to build shelters. “There were quite a lot of skirmishes when we were trying to build this wall on the hillside,” Ray recalls, “but we’re only talking about 50 or a hundred people at most. In the end, we gave up and ended up with a load of freeloaders on the hillside.”

Over half a million, in fact, camping out on what became known over the weekend as Devastation Hill. John Giddings, who would come to revive the festival in 2002 and run it as a major part of the UK festival season to this day, remembers arriving at the 1970 festival as a schoolboy. “You walked over the hill and it was like the Battle of the Somme. You saw 600,000 people in a field, it was one of the best things I’ve ever seen in my life. I’d never realised until that moment that there were that many people who liked the music I liked. It was incredible to be a part of something so big. You could talk to anyone, because it was a shared experience. It was a rite of passage.”

From the off, the crowd showed signs of rowdiness. On the opening Wednesday evening Kris Kristofferson, whose set was hampered by a sound system that wasn’t built to reach 600,000 people, was booed offstage when the audience misunderstood his song “Blame It on the Stones” as an attack on The Rolling Stones rather than their rock-fearing critics. “It was a total disaster,” he said later. “They just hated us. They hated everything. They booed us, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Sly Stone; they threw s*** at Jimi Hendrix. At the end of the night, they were tearing down the outer walls, setting fire to the concessions, burning their tents, shouting obscenities. Peace and love it was not.”

Murray Lerner’s 1997 film Message to Love, which documented the festival, also emphasised the troublemaking element of the crowd, and several performers’ sets were certainly disrupted by militant stage invaders. Joni Mitchell had her Saturday afternoon set interrupted by a bongo-toting hippie named Yogi Joe, ranting about the encampment of hay bales that people had built and named after Dylan’s “Desolation Row”. Sly and The Family Stone cut their rousing Sunday dawn show short when one of the cans the crowd were throwing at another political interloper hit guitarist Freddie Stone.

Police confiscated bikes and weapons from Hell’s Angels at mainland ports, and undercover officers in hippie wigs made dozens of drug arrests onsite – a hat passed around the crowd raised £1,500 for their bail. Throughout the weekend, the perimeter fences came under attack from the free-festival extremists. On the Sunday afternoon, compere Rikki Farr went into an onstage meltdown, yelling “we put this festival on, you bastards, with a lot of love, we worked for one year for you pigs and you wanna break our walls down and you wanna destroy it? Well you go to hell!”

Farr would later claim his rant was inspired by Maoists at the front of the crowd who’d been handing out leaflets demanding the destruction of the perimeter. The group had already sent him a Coke can with a bullet in it and a note reading “the next one’s for you”, now he claimed they were spitting on a priest who was onstage making a plea for donations to help people who had found their way to the local church on bad trips or robbed of their get-home money. With the ticket offices already abandoned, the festival was declared free.

Yet the police report cited the entire event as no worse than an average football weekend and Foulk claims the crowd were, by and large, a dream. “Apart from a tiny fringe minority in 1970 that vast crowd were incredible,” he says, “really decent and friendly. We did have a fringe element that were objecting… there were a couple of attacks on the arena wall on occasions, but they were like a fleabite on an elephant, it was nothing.”

And the decision to declare the event a free festival? “It was a stupid stunt by the compere. We’d stopped taking money on the gate, it was Sunday afternoon, the last day. There were very few people coming in, a trickle. They decided ‘let’s just tell everyone it’s a free festival from now on’ as a stunt. The show was going beautifully, I think everyone was completely gobsmacked when the compere came out and said, ‘we’re gonna be a free festival from now on.’ I think they thought it’d be good for our film.”

In reality, the largely celebratory crowd did indeed have a very British Woodstock. They bathed nude on the beach. They sang along with Tiny Tim to “Land of Hope and Glory” as a union jack hot air balloon sailed overhead. And they whooped at the sight of 11 friends of Brazilian Tropicalia musicians Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso dancing together in a gigantic plastic red dress then, one by one, sashaying offstage naked.

Highlights were plentiful. First to play on Saturday morning, John Sebastian was reunited unexpectedly onstage with his Lovin’ Spoonful co-founder Zal Yanovsky, and received three encores for the gesture. Emerson, Lake and Palmer played only their second ever show, with Keith Emerson stabbing his piano dressed in a sequinned bolero jacket and tights while assistants fired cannons at the side of the stage. Miles Davis was, according to Foulk, “in the process of trying to do crossover with Sly Stone and Hendrix, that was really exciting stuff”, and The Voices of East Harlem received several standing ovations. “They were about twenty schoolkids from Harlem in New York and their teacher doing gospel songs,” Foulk says, “and they were real rock’n’roll. In the middle of the night in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight, it was incredible.”

Giddings recalls an unexpected cultural touchstone emerging from the lengthy changeovers between acts. “This is where ‘Where’s Wally?’ comes from. There was a roadie called Wally and they were calling out for him onstage, and the whole audience started shouting out ‘Wally? Wally!’ In between artists, everyone would shout out the same thing.”

Backstage, with the hill invasion causing cash-flow problems and the scale of the event escalating, a certain confusion reigned. Early on, Farr had announced onstage that Neil Young would make a surprise appearance later in the weekend, but Young’s manager was stopped by the police for drug possession en route from London in his white Rolls-Royce and, minus representation, Young jetted back to the US. The Everly Brothers refused to show up because they didn’t receive transport fees upfront, and rumours abounded of Leonard Cohen making all manner of diva demands. Faulk, however, remembers quite the opposite: “Leonard Cohen was nothing but a total gentleman,” he says. “We didn’t have the balance of his fee – we’d paid him half in advance – so I had to go and find him at about two o’clock in the morning and explain that we would understand if he didn’t want to play. He turned round and said, ‘we’ve come here to play and we’re gonna do it, we don’t blame you for the situation.’ He was as charming as could be.”

The festival’s lax schedule brought its own issues. Mungo Jerry turned up happy to play even if they didn’t get paid, but had their slot shifted so many times they simply went home. And Foulk remembers finding the managers of ELP, The Doors and The Who locked in a heated debate about the running order. “Nobody wanted to follow The Who; Emerson, Lake And Palmer didn’t want to go on first, they wanted to be on in the dark; and The Doors probably wanted to go on first – it was an impossible situation to square this conundrum, so I walked away in the end saying, ‘I’ll have to leave it to you, I give up.’”

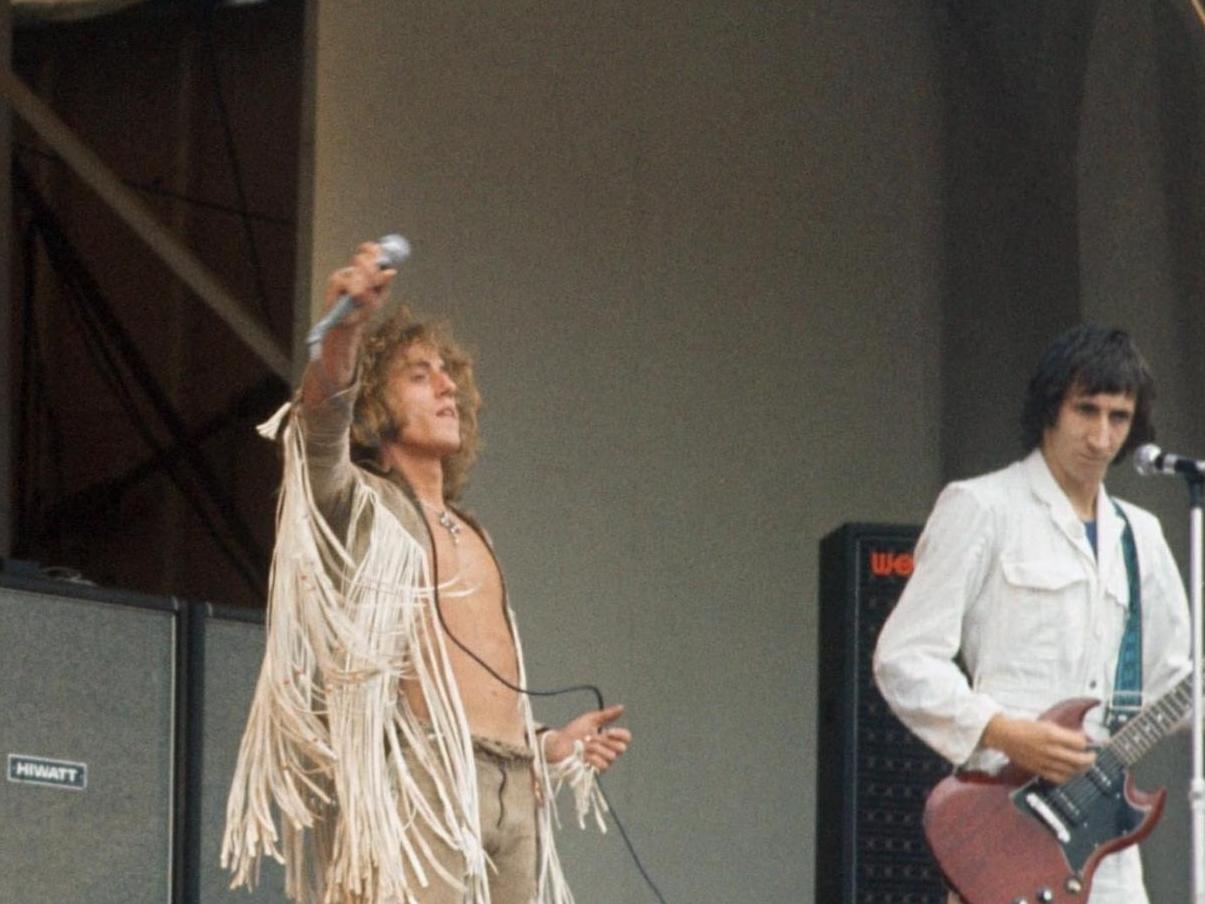

The bands themselves were locked in a drinking contest, with The Doors’ Jim Morrison taking on The Who’s Roger Daltrey in alcoholic combat before hitting the stage. Adding to Morrison’s jetlag and stress – he was due back in Miami the following Wednesday for trial after allegedly exposing himself onstage at Florida’s Dinner Key Auditorium – the contest might have muted The Doors’ famously dark and downbeat set, but it fired up The Who’s 2am firestorm. With hits like “Substitute”, “My Generation” and “I Can’t Explain” bookending a full performance of Tommy, their set was a turbulent triumph. It saw Pete Townshend star-jumping and windmilling in a white boiler suit, Daltrey lassoing his microphone in four-foot sleeve tassels and the skies strafed with Second World War spotlights. It’s considered their most memorable show ever.

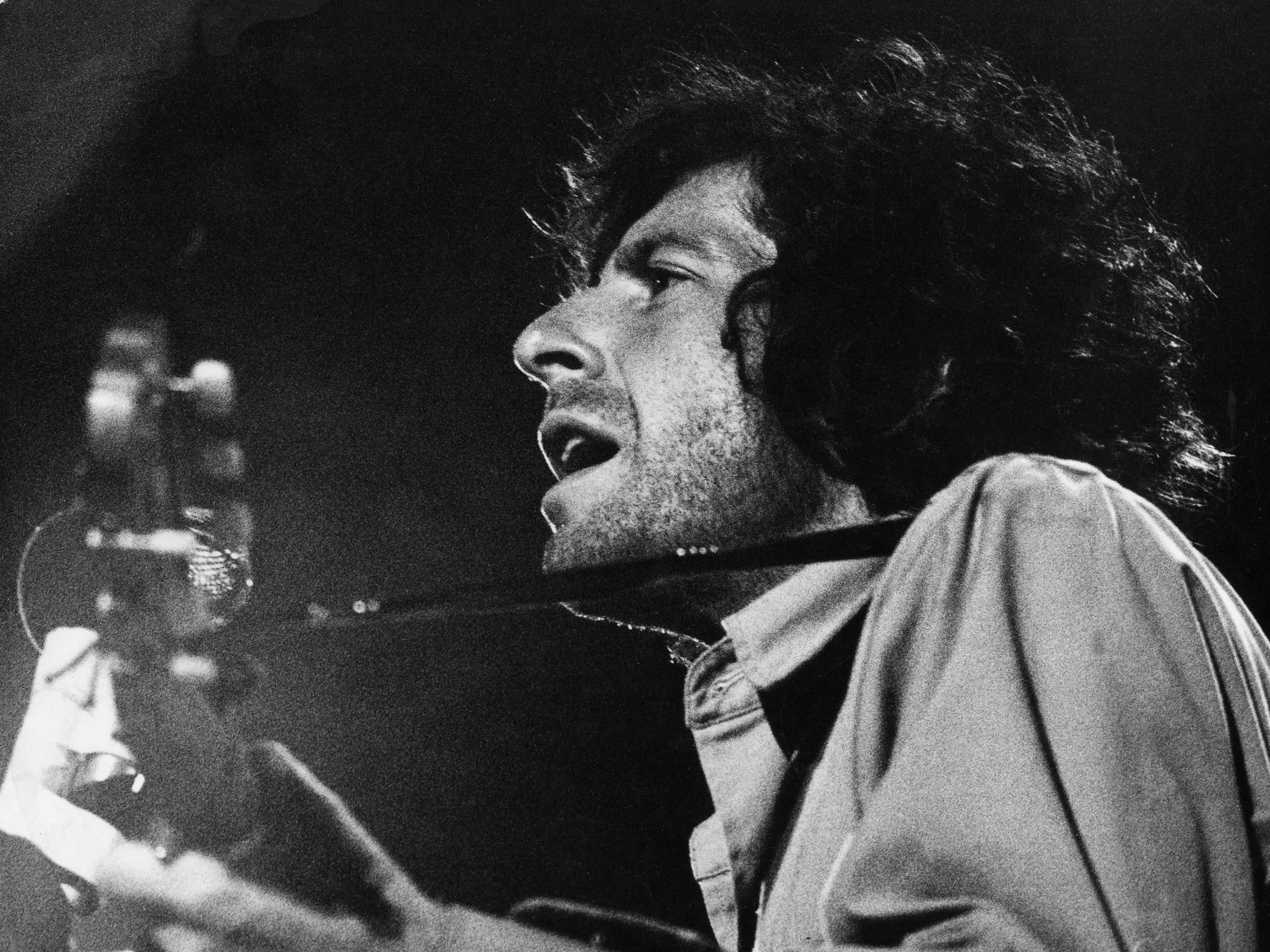

In terms of historical impact, though, it was Jimi Hendrix’s set late on Sunday night that sealed IOW 1970’s legend as the definitive full stop on the age of Aquarius. “Look at that,” Jim Morrison said to a reporter backstage, watching Hendrix head to the stage in his full psychedelic guru regalia, “it’s like a priest going to the altar.” There he played a powerful, exhilarating set that opened with fervent NYC blues deconstructions of “God Save the Queen” and “Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”, in honour of Britain’s experimental influence on the era, and ended, two hours later at 4am, with firebrand takes on “Purple Haze”, “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” and “In From the Storm”. “Maybe one of these days we’ll join again,” he said as he finished, but Hendrix had well and truly left the building. Just 18 days later he would be dead from a barbiturate overdose in London, aged 27.

Faulk saw no sign of his drug problems on the day of his last British show. “There are various reports to say that he was out of it on drugs during his performance,” he says. “You can see on the film, very clearly, he may have been on something or other, but he wasn’t heavily out of it at all – he couldn’t have done that performance if he was.”

The entire future of British festivals could have died with Hendrix, were it not for the police. In the wake of the Isle of Wight – which Foulk estimates lost him at least £100,000 – parliament added a section to the Isle of Wight County Council Act of 1971 banning all gatherings of more than 5,000 people on the island without a special licence. “I spent two days at this festival incognito in my hippie outfit,” Woodnutt told the House of Commons, “and the scene both during and after the festival was one of indescribable squalor and filth.” Luckily, the police report was glowing. “They were trying to make the Isle of Wight Bill go national,” Foulk says today, “and it was only the evidence of the chief constable of Hampshire talking [positively] about the Isle of Wight that they decided not to proceed with the legislation, otherwise festivals would’ve been banned everywhere. We called him the saviour of festivals in the UK.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments