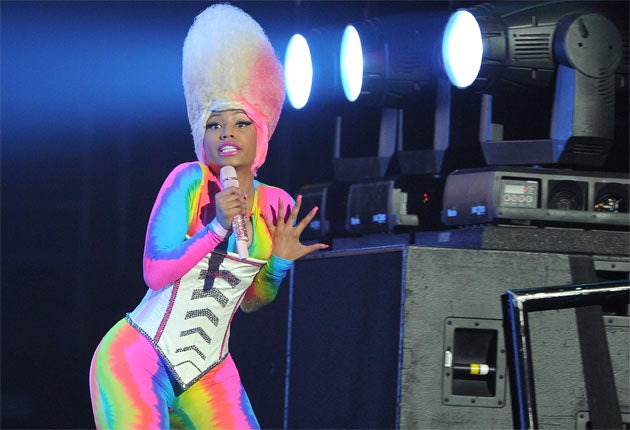

In the pink: First lady of hip-hop Nicki Minaj is a bewigged global phenomenon

But as the singer tells Nick Haramis, she is still a determinedly private person

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nicki Minaj breezes into the room, wearing what must be the most business-casual hairpiece she owns. Always seen in one of a seemingly endless procession of outlandish wigs, today the 26-year-old has opted for a relatively demure look, choosing a black wig with a blunt fringe. Like a pouty feline, she settles into a settee at the London hotel, in Midtown Manhattan.

The self-proclaimed "Harajuku Barbie" is tired. For months she has been travelling the world to promote her platinum-selling debut album, Pink Friday. Of her trip to London, earlier this year, she says: "There were paparazzi everywhere. Kids were camped outside the hotel." There were so many, in fact, that security guards at The Dorchester were forced to set up barricades to keep the "Barbs" and "Ken Barbs", as Minaj affectionately refers to her followers, from storming the lobby.

Minaj's impressive rise to superstardom is almost without precedent. She was crowned as hip-hop's queen even before the release of Pink Friday in November, with guest spots on seven hit singles that spent time on the Billboard Hot 100 simulataneously – a record for a female rapper. For a time, it seemed like something was amiss if Minaj's playfully acidic rhymes were not on a track. Everyone – from Mariah Carey and Usher to Ludacris and Christina Aguilera – tapped Minaj for her jackhammer confabulations.

"Everyone wanted the Nicki Minaj special," she says, "because I added something different to every record I did." In its first week, Pink Friday sold 375,000 copies in the US, occupying second place in the charts behind My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy by Kanye West, who collaborated with Minaj on a recent smash single, "Monster", and once referred to her in a radio interview as the "scariest artist right now".

"I've always wanted fame," she says. "But when I achieved fame, I started realising that it wasn't as important as being great at what you do, or being critically acclaimed. Still, I never wish I wasn't famous."

Like anyone, though, she has her limits, which were tested on that London trip when a group of zealous female fans showed up outside the hotel room of Minaj's make-up artist, in the middle of the night. "Seven girls banged on her door and they were like, 'Take us to Nicki,'" says Minaj. Such a request does not seem entirely inappropriate, given the singer's propensity for alien-like exhibitionism and the "Nictionary", a glossary of neologisms such as "Ben" (a poverty-stricken "Ken Barb") and "Dolly Lama" (a problem-solving "Barb"). Whether Minaj likes to admit it or not, she has become their leader.

Most recently, she has been touring with Britney Spears on her Femme Fatale tour. "My mother can't grasp the magnitude of my success," says Minaj, who was born Onika Tanya Maraj in Trinidad before being raised in the New York suburb of South Jamaica, in Queens. "She couldn't tell Beyoncé from Alicia Keys, and when I try to explain the far-fetched things I'm doing, she'd rather talk about having to call the plumber."

Minaj has a tight-knit relationship with her mother (who still lives in Queens, in a house that Minaj paid for with the money she made from her first three mixtapes), and she is fiercely protective of her family, which is made clear in a few choice responses when we broach the subject. Does Minaj see her mother regularly? "Yes." Does her mother know much about the music business? "No."

The conversation quickly devolves into an uncomfortable game of twenty questions. "I'm not a trusting person," Minaj says, by way of explaining her curtness. "I think it's because I've had to deal with so many people letting me down."

She came to America at the age of five, after spending two years in Trinidad with her grandparents while her parents established themselves stateside. But the dreams she had of a picket-fence existence were quickly dashed. Minaj's father, from whom she is now estranged, became a drug addict. He stole from his family to feed his addiction and was verbally and physically abusive, culminating in an attempt to burn down their house when Minaj's mother was inside.

With the support of her mother, Minaj was accepted on to LaGuardia High School's prestigious drama course (a hoarse voice on the day of her music audition forced her to pursue acting, her second choice). After graduating, she held down a series of part-time jobs, using her wages to rent studio space.

"That whole time was so horrible," she says. "It was like torture. At the end of the day, after working at whatever job I hated, I would get all dressed up and go out with the hope of getting a record deal. At night, I was an artist, but during the day I was a slave. When I think back on that time, on the people who made my life a living hell, I want to say, 'Are you all seeing me now? This is me having the last laugh after all those years when you made it hard for me to get out of bed in the morning.'"

Success didn't come easy. After being let go from her last job in the service industry, Minaj considered abandoning her musical aspirations.

"I had no money, I had no one to call and I was out on my own," she says. "I also had the burden of not wanting to tell my mother that I was out of a job, and could I come back home?" Minaj, then 22, decided to focus on achieving the career she'd always wanted.

"Besides faith in God," she says, "the only thing that got me through that time was the fear of what would happen to my family if I didn't make it. I remember thinking, 'I don't know if this is ever going work but I'm going to give it one final try.'"

The hip-hop powerhouse Lil Wayne discovered Minaj a year later, after coming across one of her many street DVDs; he signed her to his Cash Money label in 2009. Where most producers tried to emphasise her sex appeal, Wayne encouraged Minaj to wave her freak flag, which isn't all that surprising. Wayne, who was released from jail earlier this year after serving eight months of a year-long sentence for attempted criminal possession of a weapon, has a mouth full of diamond grills and teardrop tattoos under his eyes.

Minaj's many public personas – specifically her appropriation of Barbie – have emphasised the plastic over the personal, which, for some, has called into question her authenticity as a musician.

"I'm definitely playing a role," she explains. "I'm an entertainer, and that's what entertainers do. That's what people pay for. They don't pay to see me roll out of bed with crust in my eyes, and say: 'Hey guys, this is me, authentic.' They pay for a show."

Like Lady Gaga, Minaj has come under fire for branding herself as an outcast, for personifying feelings of alienation with the hope of reaching a larger group of fans and selling more albums. Of the Gaga comparisons, Minaj says: "We both do the awkward, non-pretty thing. What we're saying – what I'm saying, anyway – is that it's OK to be weird. And maybe your weird is my normal. Who's to say? I think it's an attitude we both share."

While filming Nicki Minaj: My Time Is Now, a documentary that was broadcast on MTV last November, Minaj started to worry that she had given too much, when she welled up with emotion while discussing her late grandmother. "I was afraid I'd been too real, that I'd shown too much of the actual person behind Nicki Minaj," she says.

"Someone once told me, 'People love the façade of pop stars. It's not good to be a real person.' So I lost sleep over it. But then I met tons of people who said, 'I've become a fan of yours after watching that documentary.' I'm realising now that I'm never really going to know the rules. I just have to play."

Read the full interview with Nicki Minaj in this month's edition of the 'Red Bulletin', out on Sunday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments