Hollywood’s greatest theme tunes

Good movie music enhances the storytelling – and lingers long after the credits have rolled. Geoffrey Macnab picks some of his favourite soundtracks

Cinema is self-evidently a visual medium but without music, most films would remain earthbound. The best movie scores help films to take wing. The music becomes as emblazoned in the audience's mind as any of the images. Whether it's the rousing theme of a Western like The Magnificent Seven or The Big Country, the equally stirring music of a war movie like 633 Squadron or The Dam Busters, the haunting "la la la la" refrain that plays recurrently through Rosemary's Baby, or the insistent and ominous "shark" theme from Jaws, the soundtrack helps to define the film.

The best film music also has a life of its own. Movie themes (for example, The Great Escape) have been adopted on the football terraces. Film scores have been performed in concert halls.

The Band of the Coldstream Guards are currently making an unlikely assault on the main album charts (and have gone to No 1 in the classical charts) with their album Heroes, which features rousing renditions of "The Dam Busters", "Where Eagles Dare", "Colonel Bogey" and various other pieces of music drawn from epic war films.

"Write music like Wagner, only louder," Sam Goldwyn once instructed a composer. It's a revealing remark. All those swirling Max Steiner, Franz Waxman and Miklós Rózsa scores from old Hollywood films suggest that the studios liked to ladle it on thick. Their scores were invariably based on what the late composer Elmer Bernstein used to call a "middle-European, symphonic sensibility." They may have been writing in California but their hearts were still back in Vienna. Arguably, not so much has changed since then. Music is used in an infinite number of ways in movies but most often, it's about narrative. As the film historians David Bordwell, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson note in their book, The Classical Hollywood Cinema, "Stravinsky's comparison of film music to wallpaper is apt, not only because it is so strongly decorative but because it fills in cracks and smoothes down rough textures."

The music sets the tempo for the storytelling. It can crank up tension. (Watching horror films or thrillers, you often have the sense that the music is one step ahead of the spectator: it knows in advance just where the danger lies.) It can underline character. It can introduce deep levels of irony (in Godard movies, the music always seems to be in opposition to the images.) It can convey the sublime one moment and encourage you to buy popcorn the next. If an actor is off-key, the music can hide his inadequacy and sometimes even do his work for him.

Grief, fury, lust, awe and even boredom can be signalled far more tersely and effectively by music than they can by dialogue. The best movie scores aren't necessarily the best music. They're there to work with the visuals, not to subvert or overwhelm them.

Taxi Driver: Bernard Herrmann

As a yellow cab glides through the mist, there are martial rolls on the soundtrack, hinting at the violence lurking within the film. Then, as we see a close-up of the cab driver's eyes, we hear a jazzy, saxophone theme, full of yearning and lyricism. Herrmann had written scores for Orson Welles and Hitchcock. For him, music was a key part of film-making. "All you would have to do would be to look at any film without music and it would be almost unbearable to look at," he once stated. Herrmann was credited with moving Hollywood movie scores away from the European symphonic sound and giving them a specific American idiom. He was an ideal collaborator for Scorsese, sharing the director's intensity and his sense of longing.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Ennio Morricone

With its coyote-like wailing and ferocious changes in tempo, the main theme from Morricone's most famous score manages to keep its edge, however many times and in however many different contexts we hear it.

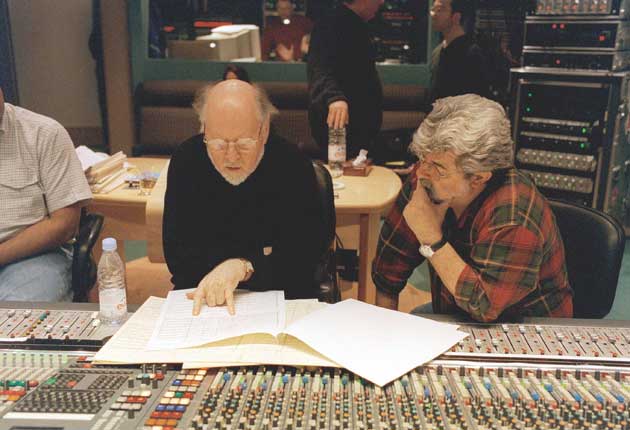

Jaws: John Williams

If ever you have the misfortune to be swimming in the Pacific and to see the fin of a great white shark edging toward you across the water, this will be the music playing in your head as you try to splash to safety. In a concert hall, Williams' monotonous and repetitive music would sound utterly absurd, but for spectators watching a shark inexorably close in on its quarry, it was the stuff of sheer terror. As Williams once said, the test of a good score isn't that you notice it. "It's like a good tailor. You don't want to know how he sewed it. You just want to know that it holds."

The Ipcress File: John Barry

Dreamy and sinister, Barry's music for The Ipcress File is more laidback and less showy than his James Bond scores. The "A Man Alone" theme was reportedly influenced by the Anton Karas zither playing in Carol Reed's The Third Man. Barry's most innovative gambit was to use the cimbalom to achieve that distinctive twanging noise.

Once Upon a Time in America: Ennio Morricone

It's the pan flute music that is so poignant here. Sergio Leone's film has a self-consciously embroiled, time-shifting narrative, complete with Proustian flashbacks. The narrative might have seemed cumbersome and even absurd if it wasn't for Morricone's magical and evocative music. The score here somehow captures both the toughness and the vulnerability of the film's protagonists: young immigrants in the Jewish ghetto of New York who become big shot gangsters but betray their friendship in the process.

The Adventures of Robin Hood: Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Korngold's famous score is more stately than swashbuckling. If Errol Flynn had taken his tempo from the music, his Robin Hood wouldn't have been nearly dashing enough either to impress Maid Marion or to out-swordfight Basil Rathbone's Sir Guy of Gisbourne. However, Korngold's music is still revived frequently in concert halls and is as much loved by classical music devotees as it is by kids who relish yarns about men with bows and arrows in green tights. Korngold was considered a musical prodigy in the Vienna of the 1920s. Europe's loss in the Nazi era was Hollywood's gain.

The Piano: Michael Nyman

Nyman's score for Jane Campion's Palme d'Or-winning film had a raw charge about it that you wouldn't expect from a composer known as a minimalist and who had worked frequently with the very cerebral Peter Greenaway. Then again, given that the characters in the film (Harvey Keitel's gruff Scotsman, Holly Hunter's mute piano-playing spinster) don't have long dialogue sequences with which to express their feelings, it was inevitable that Nyman's music would be used to heighten the film's emotional charge and its eroticism.

The Magnificent Seven: Elmer Bernstein

Bernstein wrote the themes for both The Great Escape and The Magnificent Seven. When I interviewed him in the late 1990s, I asked if he found himself humming music that has been heard everywhere from football terraces to commercials. Unlike many of the rest of us, Bernstein was able to get the music out of his mind. In the case of The Magnificent Seven, he told me, he had simply been trying to drive up the pace of a movie that had seemed on the slow side to him when he first saw it without music.

The Man with the Golden Arm: Elmer Bernstein

It's the jazzy, brassy, self-consciously hip quality that makes Bernstein's soundtrack for this Otto Preminger adaptation of Nelson Algren's novel stand out. When other Hollywood composers in the 1950s still seemed determined to ignore the world around them and to write novelettish scores, Bernstein took the boldest, most strident approach he could. He had to risk the wrath of his famously bad-tempered director to get away with writing an entirely jazz-based score. To his amazement, Preminger simply told him that he should go away and do it.

The Big Country: Jerome Moross

Critics used to talk about the idea of "the American Sublime" – 19th-century painting celebrating big, romantic landscapes with mountains, waterfalls and rolling plains. The famous Moross score for The Big Country evokes perfectly the spirit of these paintings. Its continuing cultural relevance was underlined in bizarre fashion when Atomic Kitten used the Big Country theme in their song "I Want Your Love".

'Heroes' by the Band of the Coldstream Guards, featuring performances of "The Great Escape", "633 Squadron" and other epic tunes is out now, released by Decca

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks