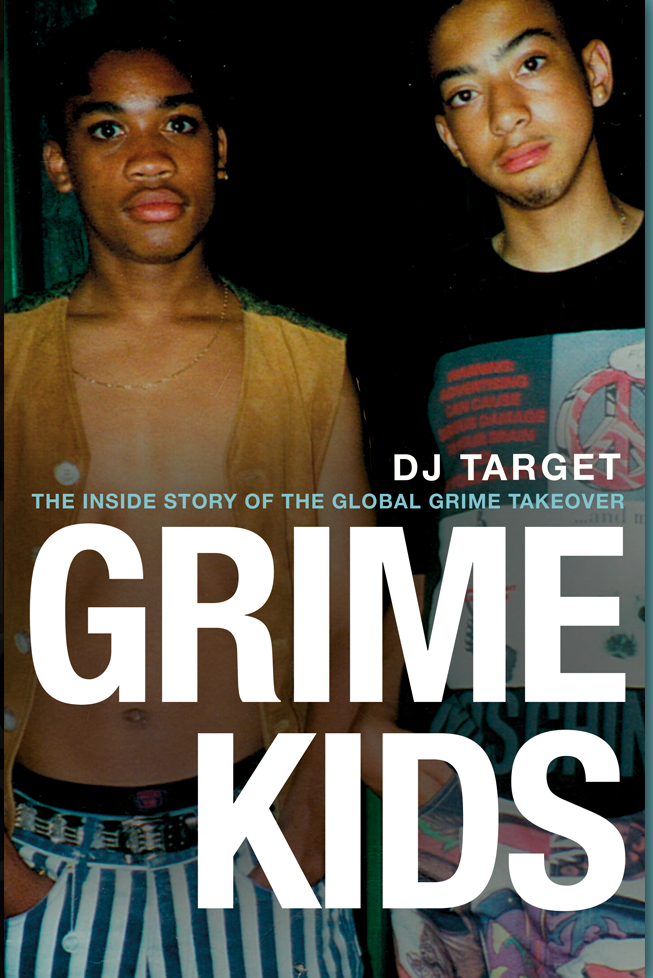

Grime was Britain's 'greatest musical revolution' – and DJ Target's written the book on it

Mates with Wiley and Dizzee Rascal, DJ Target had a ringside seat for the early days of grime. Now the 1Xtra presenter is telling all in his book 'Grime Kids'

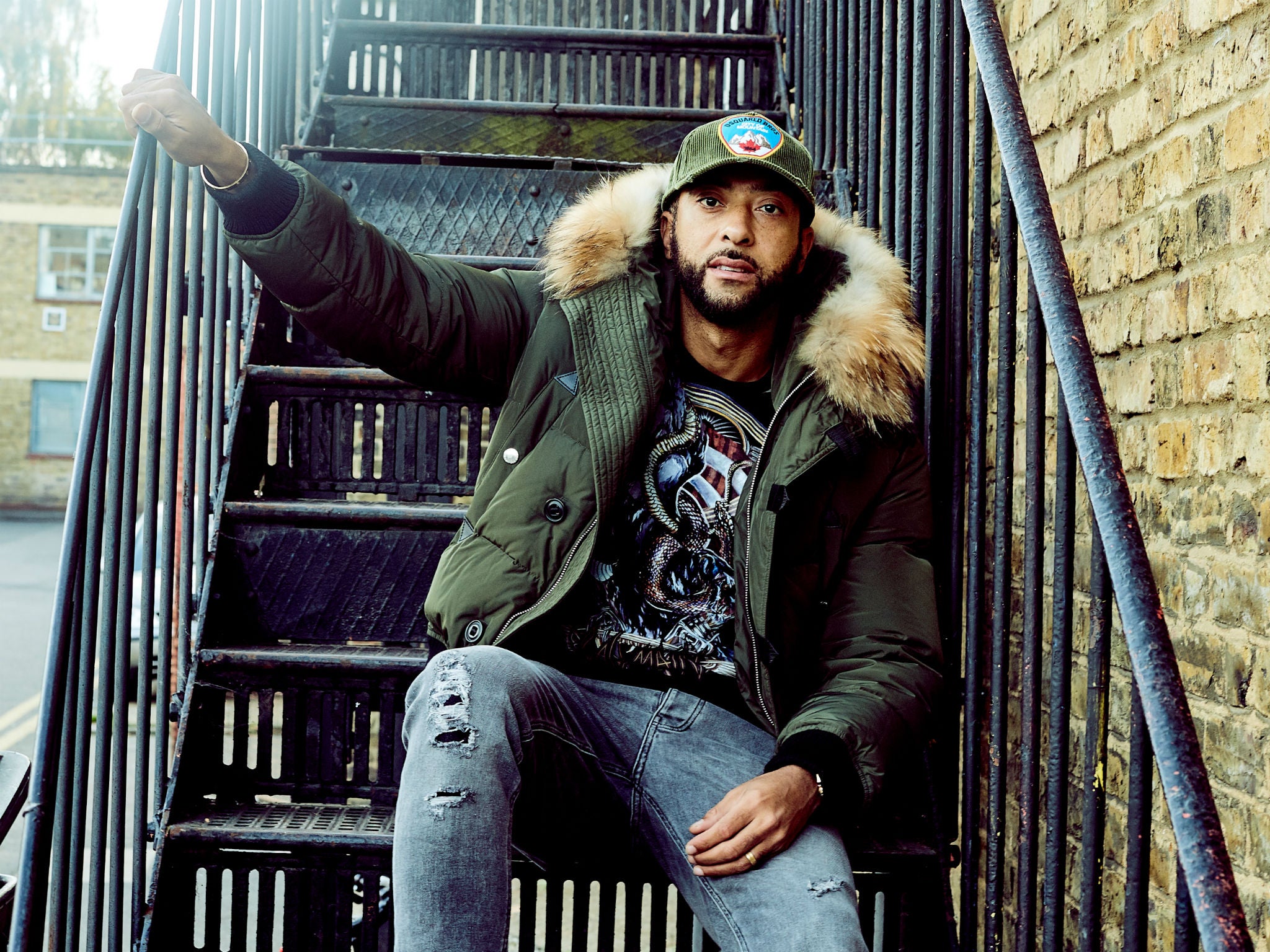

Darren Joseph, aka 1Xtra presenter DJ Target, bustles into a smart cafe near Broadcasting House, with the dazed energy of someone who rarely stops moving.

Having spent his weekend at both Manchester’s Parklife Festival and Transmission in north London, the presenter is preparing to host his evening radio show, before taking a night off to launch his latest project: Grime Kids.

The book is a personal history of how grime materialised in east London housing estates, found critical and commercial success and then lost momentum, before a fresh generation of artists gave it a new lease of life – bringing commercial success and respect from American players. If anyone still struggles to believe that a world-beating sound could be created amid a few blocks in Bow, Grime Kids is a must-read.

Joseph witnessed some key moments in grime’s gestation and rise. He was a childhood friend of Wiley; Dizzee Rascal was a younger neighbour keen to buy old jungle records. In fact, the two collaborators – now fallen-out – first met in Joseph’s bedroom.

Then a wannabe producer, later a member of the influential Pay As U Go Cartel garage crew and Roll Deep, Joseph had a ringside seat for the most extraordinary musical story for years.

But Joseph also had his own story to tell.

Nursing a restorative apple juice, he laughs at the audacity of this. “On paper I shouldn’t have been able to write this, but I just felt most of my contemporaries aren’t going to. I was in a position where I’ve been around it all and not many people have.”

And he was determined to tell his own story without a ghost writer, wanting to give his work real immediacy. His only literary inspiration was Roald Dahl. “I used to read a lot [of his work] when I was younger, so when I got stuck I used to think: how would he have made this part work?”

Joseph decided to become an author in 2016, as grime was gaining a new lease of life. For some time, the likes of Wiley and Dizzee had moved away from the genre’s roots with an over-polished vibe, while more pop-orientated acts such as N-Dubz muddied waters further. But then came a new wave of compelling MCs and producers led by the likes of Meridian Dan and Stormzy.

“People had lost focus, trying to get to the mainstream and chart success, and we really needed to hit reset. You had Tinchy Stryder and Tinie Tempah doing really well without being considered grime, so people thought they had to conform,” he recalls.

“In 2014, I first noticed a new energy coming back into grime, the same sort [as] when we were coming up in 2003 and 2004. Meridian Dan’s “German Whip” opened up the doors commercially because it was a core grime-record that did well. It gave new artists – and those around for years – a wake-up call.”

Meanwhile, Skepta had headed to New York, breaking down the barriers of its underground scene, paving the way for today’s collaborations where Americans finally take British artists seriously.

There have always been UK rappers and MCs, but grime seems to have changed the game. Joseph puts it down to a special combination of influences: hip hop from the States, Jamaican sound system culture, plus a variety of homegrown scenes – first jungle, then the smoother UK garage movement. To such styles, Joseph and his crews brought a grittier, MC-led feel.

“Before grime, there were a few British MCs, but there wasn’t a proper identity. UK artists used to look to America, dress like Americans, use their slang, and in worse cases rapped in American accents, so that wasn’t relatable to us.

“When we were younger, we didn’t have a lot of UK music to listen to. Then jungle came along, people from up the road in Hackney, talking about stuff we know. It was a melting pot for us growing up and we made something out of it that was our own. Grime has grabbed this whole generation because it speaks directly about their lives, their fashion, their social situations.”

He adds that Americans have embraced it precisely because of its very real British identity: “it’s new, different, and very distinctive. All the artists they’re listening to are speaking their truths, and in this climate that’s what’s rising to the top.”

Joseph adds that while some global stars, among them Drake and Kanye West, are supporting British artists, there is still a long way to go. Yet the author defends his claim in the book that grime is the “greatest musical revolution” to have started here, with artists evolving from outcasts to empire-builders.

In Grime Kids, Joseph relates how grime MCs replaced the romantic and celebratory vocals of UK garage with more gritty street stories. This development emerged in a variety of inner cities, but it was the particular confluence of characters, attitudes and geography in Bow that made it especially fertile.

“There was a focused hub of young people in the same area at the time that had the same things in common. We had the social set-up fuelling us: the high youth unemployment, the drug problems, not much to do.”

Instead, Joseph and his mates relied on their own infrastructure: pirate radio stations, raves, and DVDs that disseminated their sets. While the first 100 or so pages of the book paint a picture of self-sufficient youths battling lack of opportunities through drive and ingenuity, once the main players start forging lucrative careers, divisions between them begin to emerge.

There is also the threat of violence, seen explicitly when Dizzee is hospitalised after a stabbing in garage’s party capital Ayia Napa, causing the rift between him and Wiley that continues today.

In the book, Joseph refuses to go into details about the incident, but he is clear that while feuds can happen between impassioned creatives, it is not simply to do with money. “It’s life that effects relationships, changes people’s directions; people grow into something else. You start as kids in the same place, but you drift apart. In the scene, I’m sure there have been arguments over money, but it is not the cause of many fall-outs.”

And while beefs between rival MCs can signal deeper disputes, he points out that often they simply a sign of healthy competition.

“Problems may have been caused by things said on tracks, MCs going after each other lyrically,” he says, but adds that “miscommunication is a classic thing. That happens in life as much as music. But I feel for the most part grime artists have dealt with their problems in an amicable way.”

Clashing, as Joseph calls it, is influenced by both sound systems and rap battles. “It’s a sport that comes with a lot of energy.”

Misapprehension about such dynamics may have encouraged mainstream resistance to the genre, however, causing its momentum to dip during the Noughties. The dreaded form 696 that allowed the authorities to shutdown grime gigs may have been seen off, but wider prejudices remain.

In Grime Kids, Joseph discusses early meetings with record label reps who failed to understand where these council estate lads came from – and worries things have yet to improve significantly.

“I find that youngsters are going into these labels and it’s just the same. It might be even harder because the music is so prevalent every major label is climbing over each other to get the next Stormzy. It’s hard for kids coming off the estates into these massive buildings with A&Rs telling you the same stories and not knowing which one to trust.”

Joseph describes writing Grime Kids as therapeutic; he enjoyed getting down all his stories. “I was releasing all these memories that no one, or just a few people, knew,” he says.

“Telling this story has been a calling. I didn’t know before, but I was supposed to do this.”

‘Grime Kids’ by DJ Target is out now, published by Trapeze

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks