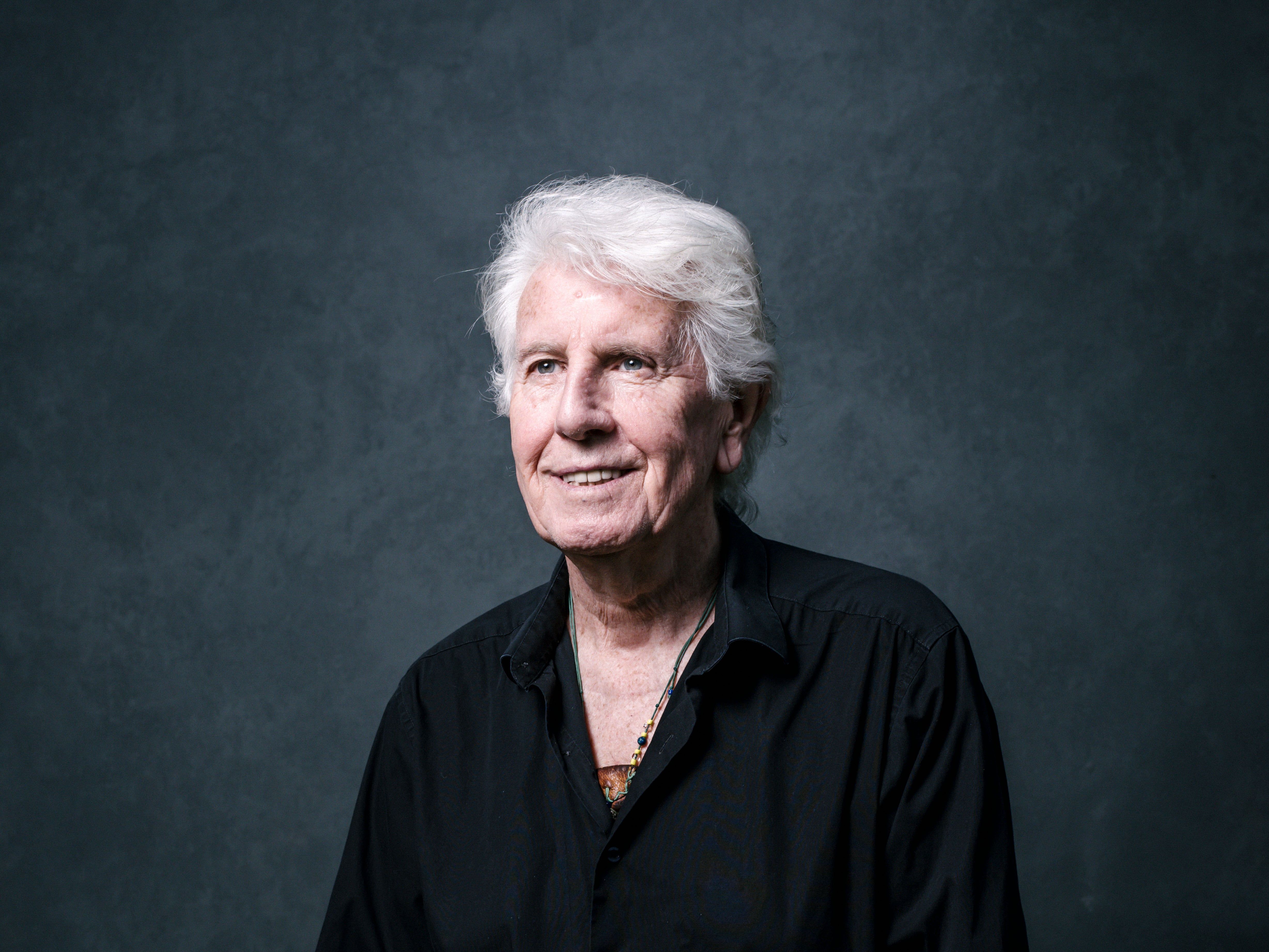

Graham Nash: ‘There’s incredible misinformation going on, particularly with Joe Rogan and Spotify’

On a new live album, the 80-year-old living legend and former Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young troubadour revisits his Seventies solo records. He talks to Kevin E G Perry about being dumped by Joni Mitchell, pulling his music from Spotify, and military madness in 2022

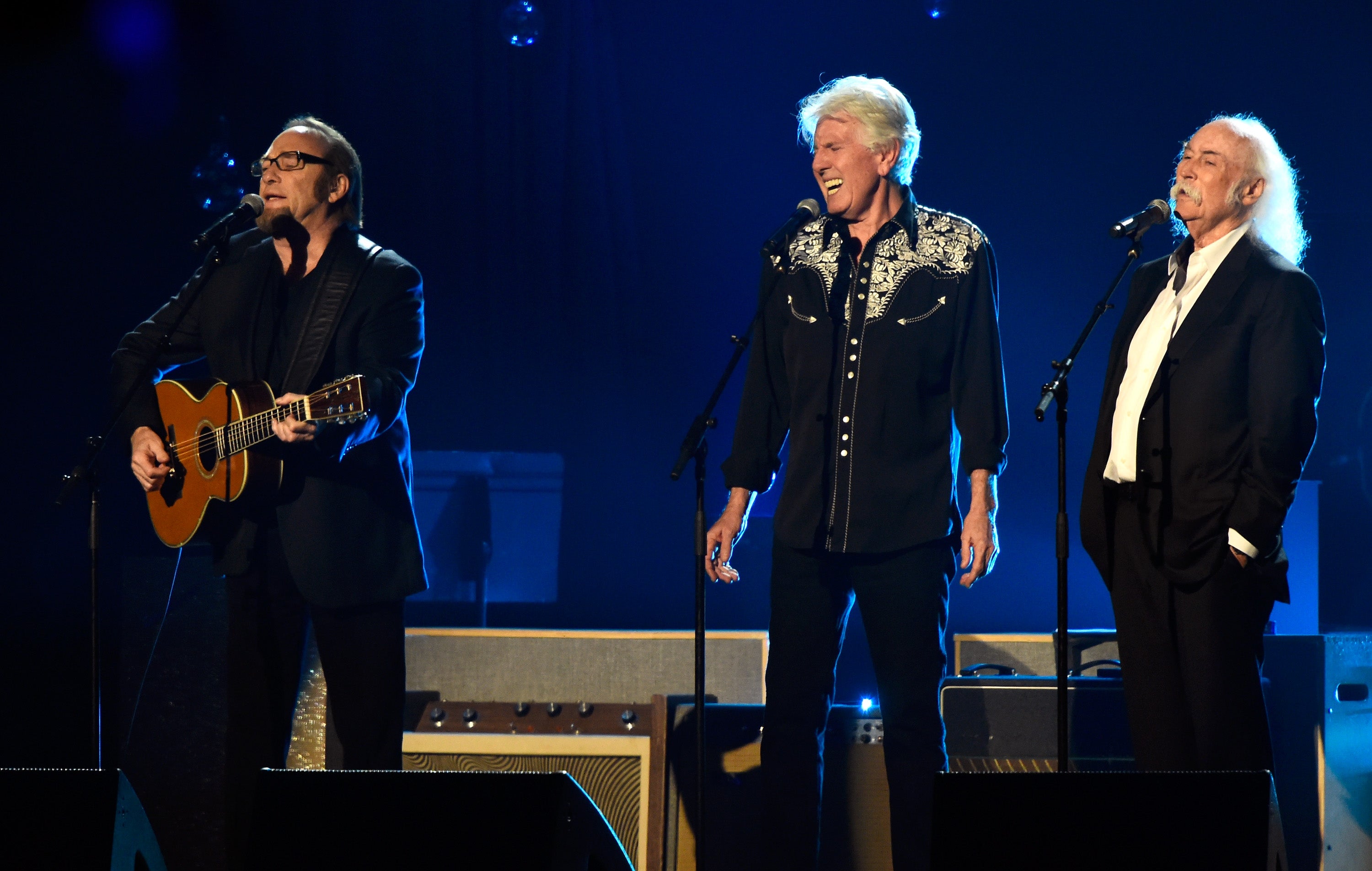

In August 1968, 26-year-old Graham Nash arrived in Los Angeles for a three-day trip, which he planned to spend sequestered with his new love, Joni Mitchell. Arriving at Mitchell’s picturesque bungalow in Laurel Canyon, Nash found the singer-songwriter hanging out with a couple of her friends, fellow musicians Stephen Stills and David Crosby. The pair played him a new song they’d been working on, “You Don’t Have to Cry”. After asking them to repeat it twice, Nash joined in to create a flawless three-part harmony. This debut Crosby, Stills and Nash performance took place with Mitchell as their audience of one. It’s a scene so perfect that you’d think it was contrived if it showed up in a biopic. “Isn’t it?” says Nash, now 80, down the line from his home in New York’s East Village. “Yet that’s exactly what happened. I’ve had a lot of those moments in my life.”

Thus began the on-again, off-again tale of one of the first and greatest folk-rock supergroups: Crosby of Californian folk-country combo The Byrds, Stills of Canadian-American rockers Buffalo Springfield and Nash of Mancunian pop group The Hollies. After releasing their sublime self-titled record in 1969, the trio added a fourth member, Stills’ former Buffalo Springfield bandmate Neil Young, before making their live debut in Chicago as a warm-up for playing the gigantic Woodstock festival. They soundtracked the era’s counterculture and continued in various iterations until splitting, seemingly for good, following a final Crosby, Stills and Nash tour in 2015. In the years since, Nash has been back on the road alone. New album Graham Nash: Live captures him in the northeastern United States in September 2019 revisiting his two solo records, 1971’s Songs for Beginners and 1974’s Wild Tales.

The disintegration of Crosby, Stills and Nash has been largely attributed to an acrimonious fall-out between Nash and Crosby, so it’s notable that several of the plainly autobiographical songs on those albums were written at a time when their friendship was at its deepest. In 1969, after the tragic death of Crosby’s girlfriend Christine Hinton in a road accident, Nash pledged to stay by his friend’s side. “We went around the world drinking, quite frankly,” he remembers. “Courvoisier and Coca-Cola, what a drink! I knew that David was in deep, deep depression about Christine. I knew that he was very fragile. I feared for his life for a short moment.”

After returning to the States from their globe-trotting bender, Nash boarded Crosby’s schooner Mayan in January 1970 for a 3,000 mile, seven-week voyage from Fort Lauderdale to San Francisco via the Panama Canal. In his 2013 memoir Wild Tales, Nash recalls loading the boat up with “a steady supply of weed and a bottomless reserve of coke”. That alone seems like a logistical headache for a crew that included Crosby and Nash at the height of their prodigious drug use, but Nash dismisses my incredulity with an audible shrug. “Yeah, well, we just took enough with us, you know?” he says. “What can you do?”

While they may have been bringing new meaning to sailing the high seas, the journey was a productive one for Nash, who returned with a cache of fresh songs including “Man in the Mirror”, “Southbound Train”, “Frozen Smiles” and “Wind on the Water”. The latter was, on the surface, about sighting a blue whale off the coast of Guatemala, but really a portrait of Crosby. “I’m not a sailor so I wasn’t watching all the stuff that Crosby was watching,” recalls Nash. “I was left alone to think and to write and to fill my notebook with ideas. I’d never sailed before, and the next thing I knew we’re going past Cuba, through the Panama Canal and then up the West Coast. What a trip for your first trip!” Despite the warmth of these memories, Nash makes it clear he has no interest in picking over the wreckage of their friendship. Life moves on, I suggest. “Yes, it does,” says Nash brusquely. “And so do I!”

Back on dry land, Nash went to Mitchell’s place in Laurel Canyon, where he received a telegram from her while she was staying in the village of Matala on the Greek island of Crete. It read: “If you hold sand too tightly in your hand, it will run through your fingers. Love, Joan”, signalling their relationship was coming to an end. “It was a devastating telegram, but c’mon, we’ve all had telegrams like that,” says Nash. “A lot of interesting songs have been written from a broken heart.”

I don’t think anybody can tell the real story of what happened with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, not even us

In response, Nash wrote “Simple Man”, which set out his feelings about their relationship in lines like: “I just want to hold you / I don’t want to hold you down.” He played it for the first time with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young at New York’s Fillmore East, with Mitchell watching from the audience. “I didn’t find out until I actually got to the microphone to sing the song,” Nash recalls. “I looked up and Joni’s sitting there, maybe the third or fourth row in. It was awkward for me, it was emotional for me, and I just dealt with it.” Did he consider not playing it? “No, not at all.” Because it said what you wanted to say to her? “Absolutely,” he says. “My relationship with Joni was a wonderful part of my life, it really was. Once you’re in love with Joni Mitchell, and you live with her for several years…” he trails off. “She’s still in my heart, you know that.”

Nash dated Mitchell after she’d dated Crosby, helping form a notorious love triangle that impacted on the band’s dynamic. It was hardly the only time that happened. “Better Days”, one of Nash’s finest solo tracks, was written about the singer Rita Coolidge. “I met Rita on the night Stephen was doing the vocals on ‘Love the One You’re With’,” Nash recalls. “He had cut the track in London and brought it to Los Angeles to put voices on. Putting voices on that night was me and Crosby, of course, a bunch of other lady singers and Rita Coolidge. That’s the first night that both Stephen and I met Rita.”

Nash asked Coolidge out on a date, but Stills rang her up and told her he was sick and that he would take her out instead. They lived together for a while before Nash, undeterred, started his own relationship with her. The “Better Days” refrain: “Don’t you cry ’cause she is gone, she is only moving on…” takes on extra bite when you know Nash is bluntly telling his bandmate she’s moving on to be with him. “Sure, it’s pointed,” says Nash. “Rita is actually playing piano with me on ‘Better Days’.” How did Stills take that? “Who cares?” spits Nash. “It was all 50 years ago, c’mon!”

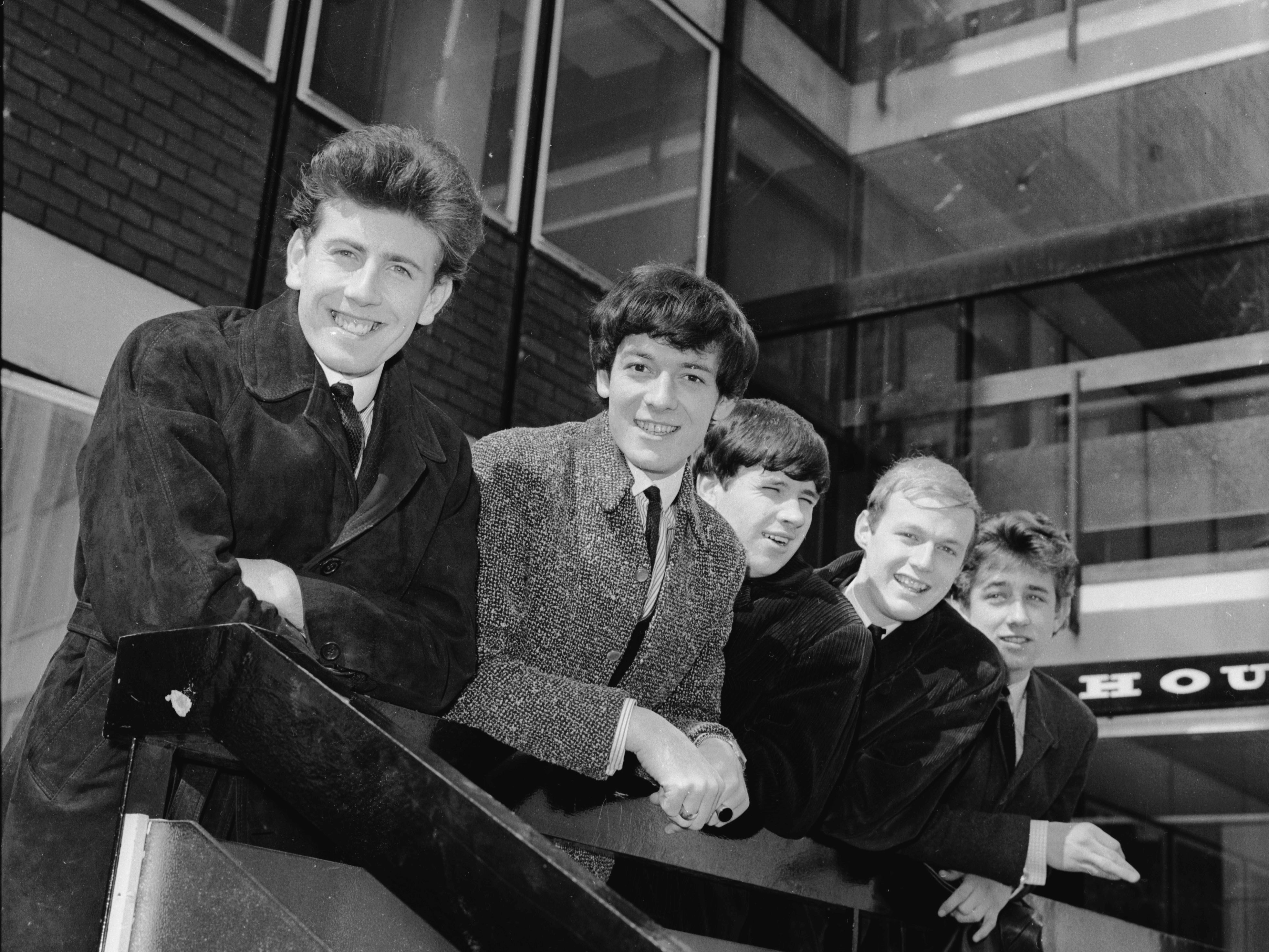

Graham William Nash was born on 2 February 1942 in Blackpool, where his mother Mary had been evacuated while the Nazis bombed Manchester. They returned to Salford, where a teenage Nash would form The Hollies with school friend Allan Clarke. They released their debut album in 1964 and quickly became one of the most successful British pop groups of the era, even supporting The Beatles at the Cavern in Liverpool. But by the end of the decade it was clear they were heading in different directions. Nash wrote “Sleep Song” – eventually included on Songs for Beginners – for The Hollies but they rejected it. “Because of the line I wrote: ‘I’ll take off my clothes and lie by your side,’” explains Nash, before putting on a Mancunian accent to mimic their response: “‘Oh, you can’t bloody write that! No, no, bloody hell. We’re a pop band, remember?’ I had very different priorities.”

While his bandmates were content drinking eight pints of beer a night, Nash was having his head turned by the emerging counterculture. Inspired by Beat authors such as Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, he took himself off to Morocco in 1967, writing “Marrakesh Express” about his travels and, he says, “the difference between booze and dope”. Around the same time he was introduced to acid by Mama Cass of the Mamas and Papas, an experience which taught him: “Everything is meaningless, and therefore it’s totally meaningful.”

Nash, who had already written the Hollies’ “Too Many People” about the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya in 1965, increasingly began to see himself as a political songwriter and social commentator. “Be Yourself”, from his solo debut, features the prescient couplet: “We needed a tutor / So built a computer / And programmed ourselves not to see.” Nash points out that at the time he wrote it, in the early Seventies, he’d never actually seen a computer. “I knew they existed, because the Eniac computer was built in the north of England in the Forties, but of course in 1971 no one had a personal computer. In fact I think IBM put out a statement where they thought there would only be a need for five computers in the world.”

In February this year, Nash joined his former bandmates in pulling their joint and solo material off streaming service Spotify in response to the controversy over Joe Rogan’s podcast spreading Covid misinformation. “One of the great things about the internet is that it gives everybody a voice, and one thing that’s f***ed about the internet is that it gives everybody a voice,” says Nash. “Some of the craziest people are using their voices for the strangest reasons. There’s an incredible amount of disinformation and misinformation going on, particularly with Joe Rogan and Spotify. When he puts on people that say: ‘You shouldn’t be wearing a mask’ and ‘You shouldn’t be getting these vaccinations because they’re putting seeds of information into your DNA…’ C’mon! It’s a f***ing virus and we’re trying to deal with it, you know? So yeah, I was happy to take my music off there.”

He is equally concerned about social media. “With Elon Musk taking over Twitter, maybe, there’s a whole other mess there,” he says. “Is he gonna let Trump back on?” Nash has long been a vocal opponent of the former president, and on the new live album drops Trump’s name in place of “The Man” into the lyrics of his anti-war hit “Military Madness”. “We don’t seem to have learned from history, do we?” says Nash, who adds that the current period of social and political upheaval is more dramatic than any he’s witnessed. “When we were going through the madness with Nixon and Watergate we thought it couldn’t get any crazier than that. This is way crazier! Our very democracy is at stake here, in very real terms. The rise around the world of right-wing autocrats is very scary.”

Nash has had a front-row seat for a whole swathe of cultural revolutions, not least being present – at Paul McCartney’s invitation – for The Beatles’ history-making recording of “All You Need Is Love” in 1967, the first global live TV broadcast. Although he knew the band at the time, he says he still found himself glued to Peter Jackson’s recent Get Back documentary about the making of The Beatles’ Let It Be. “I thought it was insanely long!” he says. “But what I came away with was witnessing John and Paul’s method of writing. When you see them standing face to face, mumbling strange words and strange melodies until somebody goes: ‘Oh, that’s cool. Yeah, I’ll put a line to that’… when you see them doing their process, and these are two of the greatest pop songwriters ever in history, that was thrilling for me to watch.”

He thinks it’s unlikely a film as revelatory could ever be made about Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s process. “Oh, God knows,” he says. “I don’t think anybody can tell the real story of what happened with CSNY, not even us.” Nevertheless, he confirms that talks are still underway with Back to the Future director Robert Zemeckis about making a documentary about the band. “I have an appointment to call him at four o’clock today,” he says. I tell him I hope it happens, because, like The Beatles, the music they made together will surely be treasured and listened to as long as humanity sticks around. Nash shoots back: “And how long do you think that’ll be?”

Despite these flashes of cynicism, Nash says he’s been inspired by a recent tour of North America on which many fans showed up with tickets they’d been holding on to since the original shows were cancelled two-and-a-half years ago. “That means hope, to me,” he says. “That means yes, it’s f***ed, but you’ve still got your ticket because you hope [live music] will come back and you hope that tomorrow will be a better day, and it will be.”

Nash remains creatively productive, and reveals that almost half a century on from Wild Tales he’s currently putting the finishing touches to his third solo studio album, recorded remotely during the pandemic with former Bruce Springsteen guitarist Shane Fontayne and Stephen Stills’ keyboardist Todd Caldwell. Given how frank and personal his first two records were, I ask Nash what he’s been inspired to write about this time around. He grows taciturn again. “Love, hate,” he says, finally. “Same s***!”

‘Graham Nash: Live’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks