Glyn Johns interview: My 50 years of producing rock classics

Producer Glyn Johns birthed umpteen rock classics, and has 50 years’ worth of stories to tell about life in the studio with Mick and Bob and co

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Next time you’re in the home of someone who lived through the golden age of rock‘n’roll – 1963-1976, from the Beatles to punk – try this simple experiment.

Go to their CD or vinyl collection and look at the sleeve notes on the classic albums, such as Beggars’ Banquet and Let it Bleed by the Rolling Stones, Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake by the Small Faces, Shine on Brightly by Procol Harum, Abbey Road and Let it Be by the Beatles, Slowhand by Eric Clapton, Mad Dogs and Englishmen by Joe Cocker, Who’s Next and Quadrophenia by the Who, Self Portrait by Bob Dylan, Stage Fright by the Band, Desperado by the Eagles, Harvest by Neil Young, Led Zeppelin’s first album, Joan Armatrading’s second and third albums, or Combat Rock by the Clash. You’ll find a phrase constantly recurring: “Produced by Glyn Johns.” Variant readings may say “Engineered by Glyn Johns”, or “Mixed by Glyn Johns”, but you get the picture.

It’s too late for the monopolies commission to look into it, but it sometimes seems that just one man was responsible for the sound of rock history. George Martin and Phil Spector may occupy higher profiles in the producer pantheon, but Johns, over the decades, has been the go-to guy for clarity and atmosphere. “Glyn created truly beautiful ‘soundscapes’,” says Pete Townshend. “He fashioned stereo pictures that were enchanting, engaging and immersive. He did this with a concentration and focus that was without par.”

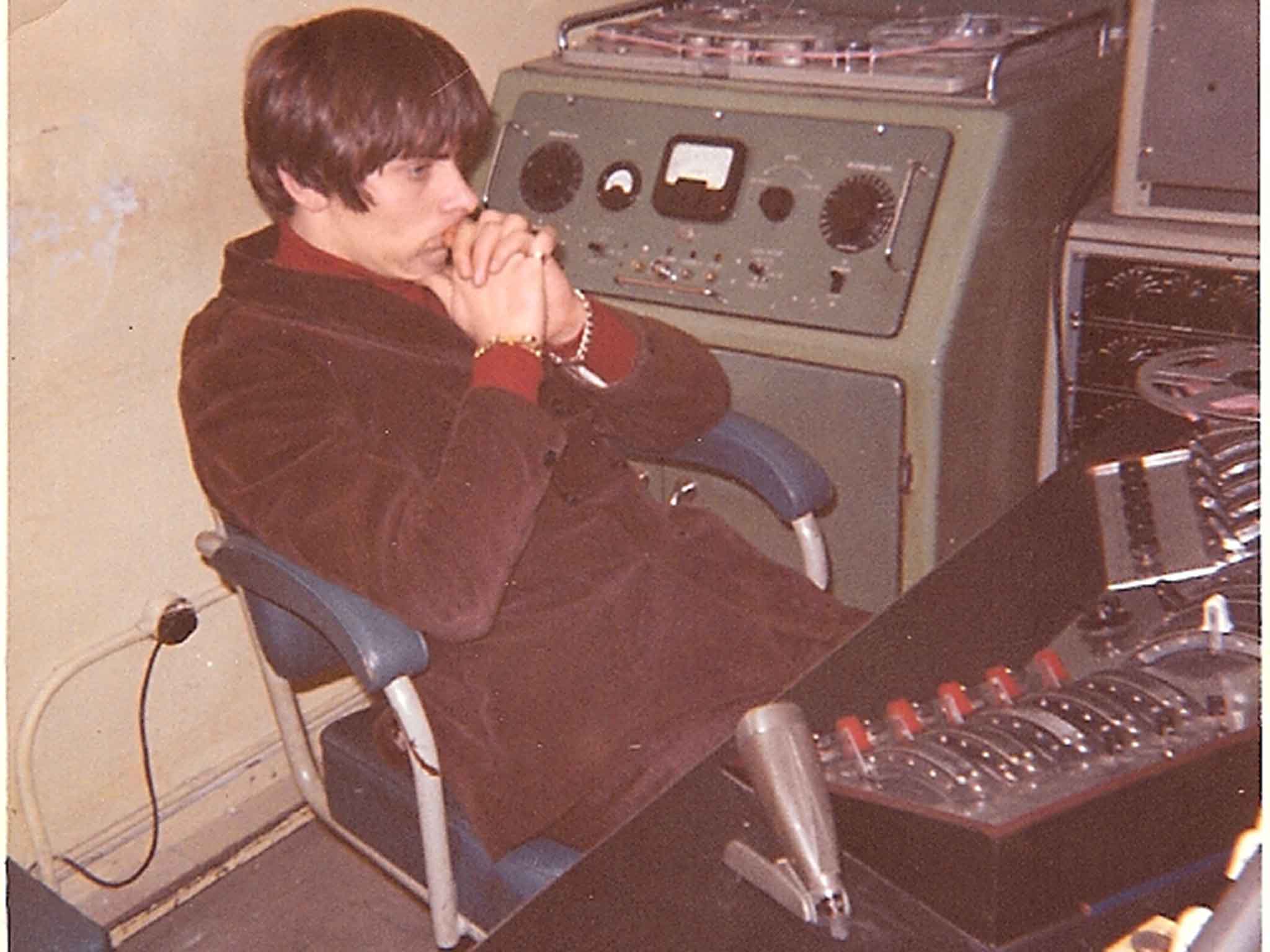

Johns’ career stretches from 1964, when he engineered the first Kinks singles, “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All of the Night,” to Benmont Tench’s You Should Be So Lucky this year. To mark 50 years in studio and stadium, he’s publishing a memoir of his adventures called Sound Man. In it he charts the evolution of recording from the days when singles were the only popular records, albums were rare, studio engineers wore collars, ties and white coats like lab technicians, and very few musicians (well, none actually) rolled spliffs and swigged bourbon during recordings.

Johns was born in Epsom, Surrey, in 1942. His father was an insurance executive. His mother played the family pianola and encouraged Glyn to join the choir. In 1959, he left school at 17 and started a band, the Presidents. Soon after, by dumb luck and sisterly influence, he found himself working at IBC in London’s Portland Place, “the finest independent recording studio in Europe”. British television’s first rock’n’roll shows – Six-Five Special and Oh Boy! – were starting, and the music was pre-recorded at IBC; the young Glyn stood on the staircase gazing at “the 1959 rock elite of the day”: Joe Brown, Marty Wilde, Billy Fury.

The teenage Johns cut a few records himself. “I thought I was England’s answer to Jim Reeves,” he admits, “but the songs were all pretty awful.” He met Ian Stewart, the legendary pianist and co-founder of the Rolling Stones; they shared a flat in 1964. Johns clearly idolised Stewart, although he was nobody’s idea of a rock star. “Stu was as ordinary a guy as you could wish to meet. He lived in Cheam. He played golf. He was working for ICI when we met – in the early days, the Rolling Stones lived off Stu’s luncheon vouchers. He and Brian [Jones] put the band together.”

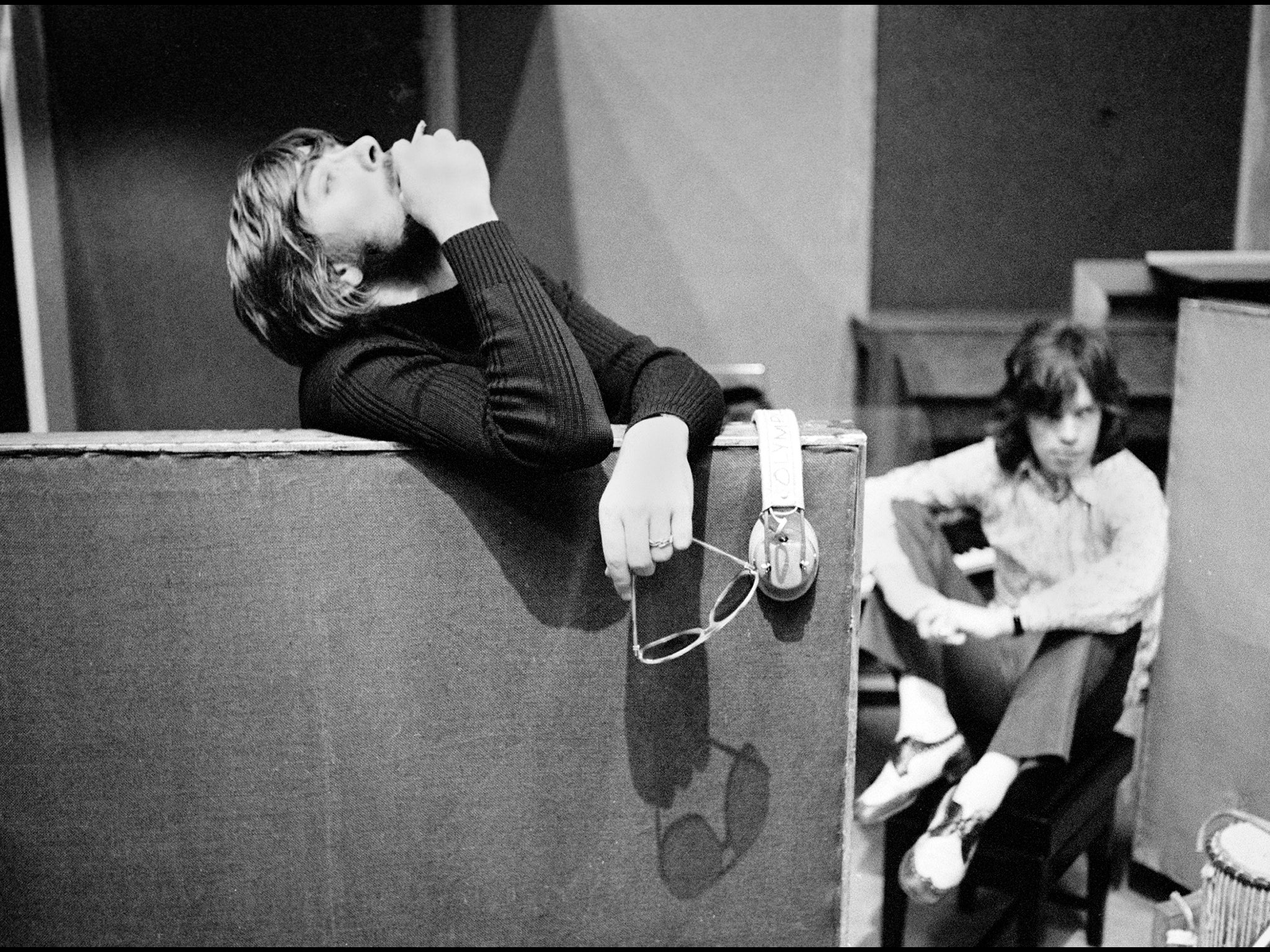

Johns’ memories of recording the Stones aren’t exactly blissful. He quotes Charlie Watts’s grumpy summation of their career: “10 years of music, 40 years of hanging around.” Were they perfectionists, I ask? “Keith would have an objective that he was aiming at, one that only he would know, and you just went on until he achieved it. If the rest of the track suffered as a result, it didn’t matter to Keith. But Mick was equally involved in the production. He was often in the control room with me, while Keith was dicking around in the studio with the rhythm section.”

In December 1969, Johns was telephoned by Paul McCartney and asked to record some new Beatles songs before a live audience for a TV show and album. The show never happened but the songs turned eventually into Let It Be, produced by Phil Spector into “a syrupy load of bullshit”, according to Johns. He watched Yoko Ono’s screaming-with-her-head-in-a-bag contributions. He rigged up the cables for the Beatles’ rooftop concert in Savile Row. He witnessed the Fab Four’s near terminal rows (during which George Harrison quit the band, but returned two days later). Sadly, he declines to reveal more details: “Part of my job has always been to respect the privacy of the artists. It’s like the doctor’s surgery or the confessional – unless you don’t like them, of course…”

Sound Man is full of striking vignettes. Here’s the legendary Howlin’ Wolf at a London session, listening to a band of upstarts mangling “Little Red Rooster” before he stops the recording, gets out his bashed-up acoustic guitar, and says to Eric Clapton: “I’m going to teach you how to play this. Somebody has to do it right after I’m gone.” Here’s Johns in the back of an Aston Martin, with the guy in the driving seat levelling a sawn-off shotgun at him because he’d upset the toxic manager Don Arden. Here he is in California, attending a Sunday drinks party in Benedict Canyon at the home of Roman Polanski and his wife Sharon Tate (“absolutely delightful, stunningly beautiful and very, very pregnant”), six weeks before she was murdered by the Manson Family. And here is Johns’ first meeting with Bob Dylan, who confided that he’d had this idea of making a record with the Stones and the Beatles, and asked Glyn if he’d mind sounding them out. (He did. Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger turned the idea down flat.)

“Dylan’s a fascinating character,” says Johns. “When I finished recording his European tour in 1984, he and I had to choose which performance of which song to use from eight or nine concerts. He single-handedly chose the worst performances. I assumed he was testing me, because he let me win in the end. Afterwards, I had him on the phone every night for a week, talking about songwriting. He was very pleasant.” Did he go to hear Dylan in concert still? “No, the element of risk in getting your money’s worth is too great.”

The note of asperity is characteristic. Tall, white-haired and strikingly handsome at 72, Glyn Johns alternates, conversationally, between infectious gasps of laughter and a death-ray glare of disapproval. You can imagine how often he deployed the latter in all-night studio sessions with Humble Pie or the Faces, being the only guy in the room who wasn’t on stimulants. Did he really never take drugs with the rock’n’roll titans? “It pissed me off, the assumption that, to be in with anyone famous, to be cool in that group, you had to do what they were doing. I thought: fuck you, I don’t want to, certainly not to be in with you. I also had no desire for it, and I couldn’t do what I do as an engineer or producer if I was in a non-natural state. I have enough trouble with the state I’m in already.”

He’s bracingly rude about over-praised bands, including Santana (“I turned them down at the beginning because I thought they were boring – he’s a very average guitar player”) and most of punk, which he calls “atrocious – an expression of aggression and nothing to do with music at all”, though he was impressed by the “cleverness, intellect and huge sense of humour” of the Clash. He mixed their Combat Rock album and hit it off sublimely with Joe Strummer.

By contrast, he’s ecstatic about “those hair-parting, adrenalin-pumping moments when I’ve been in the room while something amazing is going on.” One was the recording of Who’s Next in 1971. The first track they recorded was “Won’t Get Fooled Again” with its fiddly synthesiser, power chords and blitzkrieg drumming. “We were recording at Mick [Jagger]’s house, Stargroves near Newbury, and I’m outside in the studio truck, playing in the synthesiser and hearing them locked relentlessly on the beat right through the song. I was blown away. I knew it was a marker in the evolution of popular music.”

Johns shows no inclination to retire – he has two projects on the go for 2015, “with a Californian duo who I think are really good, and with one of the acts I used to work with long ago.” But what exactly has he been for 50 years – a gifted technician or a sonic auteur? “I see what sound engineers do as like painting. A good artist could paint that table so that it looks nothing like a table, or it looks like a photograph of a table. Engineers do that with sound.” He smiled. “One constantly gets credit for working on records that people have a special fondness for. I may have helped tweak them in some way – but really, I was just very lucky to be there.”

‘Sound Man’ by Glyn Johns is published by Blue Rider Press (US)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments